Science and Religion in Times of Plague

Calvin and Luther warn against the simplistic assumption that religious liberty is opposed to medical expertise

In the late nineteenth century, scientist John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White, the first president of Cornell University, argued that the historical relationship between religion and science—including medicine—was intrinsically defined by conflict. The Draper-White "conflict thesis" has not only proven to be massively influential in both academic and public spheres but remains quite intransigent. Although scholars such as Gary Ferngren and John Brooke have reevaluated this argument in favor of more variegated typologies or a "complexity thesis," it is tempting to view the response to the COVID-19 pandemic by various American religious groups as affording some confirmation of the Draper-White position.

Resistance to public health directives by Hasidic Jewish communities and Evangelical Christian churches across the country has been well documented; fueled by particular understandings of "religious liberty," these conflicts have been adapted into legal dramas reaching the elite stage of the Supreme Court. The court recently barred New York public health officials from imposing restrictions on religious gatherings. Apparently taking the Draper-White hypothesis as an unstated given, Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh affirmed the claims of the plaintiffs that the medical recommendations of the state’s health department impinged on their religious liberties. Their opinions portrayed an open conflict between secular causes, allied with medical authorities, and religious institutions, and they cast themselves as defending churches from the state’s favoritism toward such secular establishments as bicycle repair shops. Justice Sotomayor in her dissent warned: "Justices of this Court play a deadly game in second guessing the expert judgment of health officials about the environments in which a contagious virus, now infecting a million Americans each week, spreads most easily."

So what are scholars of religion to make of this uniquely contentious moment? Some historical perspective may be gained by comparing such defiance of medicine's tyranny with the views of Calvin and Luther, who also lived through outbreaks of plague.

Few theologians championed God's benevolent providence more passionately than John Calvin. Even so, Calvin expected believers to act with prudence, including a responsible embrace of medicine. Calvin considered the remedies of medicine a gift of the Spirit of God; consequently, to ignore or neglect medicine he considered quite egregious. "For by holding the gifts of the Spirit in slight esteem, we contemn and reproach the Spirit himself. What then…shall we say that they are insane who developed medicine, devoting their labor to our benefit?"[1] The reformer was extremely invested in the field of medicine, and not just because his personal health was notoriously precarious. Calvin's writings reveal a facility with medical texts, and he even dedicated his biblical commentary on Timothy to his personal physician. Moreover, Calvin's Geneva instituted an extensive public health infrastructure. In addition to the employ of doctors and barber-surgeons, these public services—facilitated by a network of deacons—extended to employing guardians to care for the sick and disabled, financially supporting families when the primary provider was incapacitated, paying for burials, and supplying the local plague hospital. For Calvin, to ignore the merits of medicine not only disenfranchises one's neighbors but also actively insults God.

In a similar vein, Martin Luther's 1527 "Whether One May Flee from a Deadly Plague" addresses the question of how Christians should react in the face of an epidemic. The treatise is a reasoned balance between theological reflection and practical considerations, where Luther's primary concern remains the welfare of the sick and vulnerable. But one candid passage, in which Luther addresses those who openly flaunt medicine, is of particular relevance to our present context:

They disdain the use of medicines; they do not avoid places and persons infected by the plague, but lightheartedly make sport of it and wish to prove how independent they are. They say that it is God's punishment; if he wants to protect them he can do so without medicines or our carefulness. This is not trusting God but tempting him. God has created medicines and provided us with intelligence to guard and take good care of the body so that we can live in good health.[2]

Luther's argument is actually more severe than Calvin's, cautioning that those who disdain medicine could be guilty of suicide or worse: "it is even more shameful for a person to pay no heed to his own body and to fail to protect it against the plague…and then to infect and poison others who might have remained alive…He is thus responsible before God for his neighbor's death.” Luther's advice is eminently practical, entreating his audience to "use medicine; take potions which can help you; fumigate house, yard, and street; shun persons and places wherever your neighbor does not need your presence or has recovered, and act like a man who wants to help put out the burning city. What else is the epidemic but a fire which instead of consuming wood and straw devours life and body?" He points to biblical passages about leprosy as divine endorsement for quarantines and concludes his treatise with a consideration of how burial practices affect public health. He also ultimately concedes the limits of his own expertise: "I leave it to the doctors of medicine and others with greater experience than mine in such matters to decide.”[3]

Calvin and Luther both attributed a pedagogical or edifying function to illness, but their overriding support for the art of medicine evinces a theologically motivated alliance between church communities and public health initiatives. This is exactly the relationship that the University of Chicago's Aasim Padela, MD, advocated for in an editorial for the Chicago Tribune last April. His argument remains just as relevant today, especially with the transition to vaccine disbursement. Historical examples such as Calvin and Luther are invaluable resources towards negotiating fruitful relationships between communities of faith and public health authorities. Happily, these reformers are not the only sources that problematize the Draper-White thesis. One of the most decisive influences promoting smallpox inoculation in colonial America was Cotton Mather. More recently, the Vatican ruled that COVID-19 vaccines, even those whose research relied upon the use of aborted fetuses, were "morally acceptable."

Of course, scholars of religion will have much to consider once the COVID-19 pandemic is successfully behind us, but we should be wary of allowing the response of some religious practitioners to cement a historically dubious oversimplification. Throughout history, as today, plenty of religious groups have made a responsible view of science central to their ministry; when considering groups that do not, we must examine their specific context and history, rather than assuming they stand in for some essentialized “religious” perspective on science.

[1] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed. John T. McNeill, trans. Ford Lewis Battles (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006), Book II, chapter 2:15, 273-4.

[2] Martin Luther, "Whether One May Flee from a Deadly Plague," in Martin Luther's Basic Theological Writings, ed. Timothy F. Lull (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1989), 748.

[3] Ibid., 748-753.

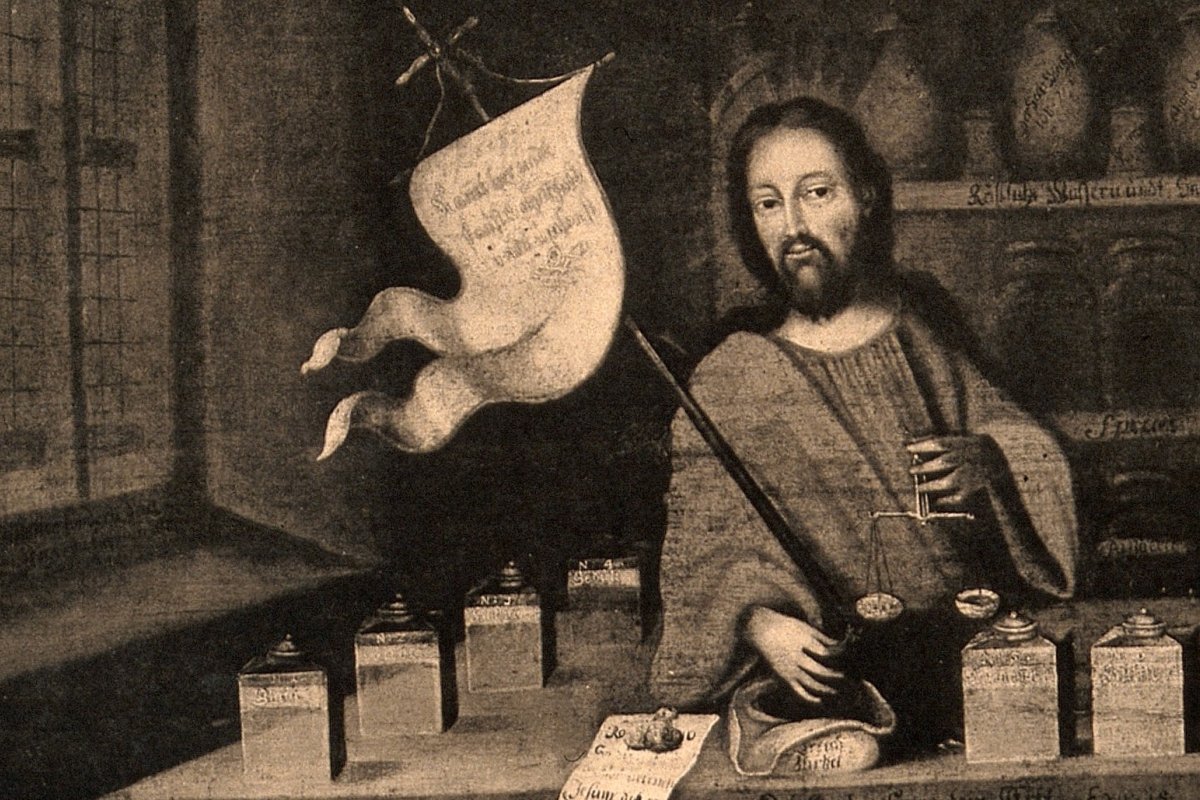

Image: Christ as Apothecary. (Reproduction of a photograph of an oil painting after J. Marie Appeli, 1731, via Wikimedia Commons)

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.