“The seeds of compassion and duty”: An Early Americanist Take on Healthcare

Imagining a future for American healthcare by revisiting our past

In December of 1775, a Massachusetts woman named Molly Forbes discovered a hard spot under her nipple. She was treated with a plaster, revealing an ulcer. This was a second occurrence, and the hardness had spread throughout her breast and into her glands. Continued treatment with plasters offered some relief. Her health nonetheless worsened, and she died in January, leaving behind young children and a grief-stricken husband. There is no record of the cost or payment for her care.

A few years ago, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. She had felt no lump; it was detected at a routine mammogram. She had a successful lumpectomy. The laboratory analysis, however, revealed a microscopic amount of cancer had spread into a node. She began chemotherapy, followed by radiation. Her prognosis was good. Medicare and a purchased supplemental plan covered her medical expenses.

It is hard to fathom what early Americans would think about healthcare today.

Medicine has changed greatly, and much of the industry around medicine, including health insurance, did not exist in the eighteenth century. We share experiences of embodiment and pain with people in the past, but I try not to elide the significant differences. We cannot assume a common, transhistorical experience of suffering and its meaning—or of the demands of human life and human care.

So, what do we share with early Americans? How can they help us think about the current healthcare debate? Despite our considerable distance, I would argue that we share something significant: a sense of duty to care for the suffering. A community cared for Molly Forbes; a community cared for my mom.

Today, we don’t hear much about the social duty of providing healthcare, yet it seems to me that it’s the heart of the matter. You might hear healthcare described as a right, but a commitment to rights depends on duty; our society has a duty to further the conditions that make possible individual rights. For early Americans, the sense of duty to relieve suffering came from a variety of perspectives. “Duty” evokes the sense of calling or mission found among eighteenth-century Protestants. Duty also stemmed from Enlightenment-era conceptions of sensibility and the sympathy it engendered; the ability to “feel another’s pain” and the desire to relieve it were seen as crucial to both human reason and the progress of society. Many early Americans grounded their sense of duty in both religion and reason.

Take, for example, the physician John Redman, who in 1787 became the first president of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, America’s first professional medical society. He was also a devout Presbyterian and mentor to Benjamin Rush. Redman’s Calvinist faith informed his practice and his sense of duty. He longed to “serve our generation faithfully according to the will of God” and described God’s direction throughout “the voyage of life.”

Redman’s understanding of duty also reflected an Enlightenment-era emphasis on rationality that rooted conceptions like sympathy and benevolence in human reason. Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid described benevolence as a virtue when developed from reason: a “fixed purpose or resolution to do good when we have opportunity, from a conviction that it is right, and is our duty.” Redman celebrated such benevolence among his fellow physicians, urging the College to the “cause of humanity,” and toasting the “individual practitioner, who makes the health, Comfort, & happiness of his fellow Mortalls one of the chief Ends and delights of his life.”

Like Redman, many early Americans found their sense of duty informed by both a Christian calling and Enlightenment-era ideas of humanity. The Puritan Cotton Mather and the Methodist John Wesley saw medicine as a gift from God to be developed and shared to alleviate human suffering. German Pietists made medicine a central part of their missionary efforts. During the Yellow Fever epidemic in 1793 Philadelphia, African American nurses described their work as a duty forged by feelings of fellow humanity as well as their sense of God’s presence. A committee of Philadelphians, meanwhile, reorganized the hospital and cared for orphans, citing God’s direction and a “duty incumbent” for those “humanely disposed” to care for fellow citizens.

This sense of duty to relieve suffering also grew from lived experience. Americans today generally expect to “feel good” most of the time; early Americans were more likely to experience sickness as the norm and health as the aberration. The constancy of sickness confirmed their theology and view of society. They saw sickness as an inevitable part of the human condition—a result of original sin. As John Wesley wrote, “the seeds of weakness and pain, of sickness and death are … lodged in our inmost substance.” Or, as Cotton Mather explained, “We all deserve to be sick.”

For early Americans, the recognition of the universal reach of sickness was more important than fixating on any individual’s moral culpability. Today when sickness is associated with sin it is usually done on a superficial level, such as arguing that some people are more deserving of care than others because of previous health, financial, or so-called “lifestyle” choices. Early American Christians saw health as given by God on God’s terms and not based on human merit. You could not moralize your way to perfect health.

You still can’t.

Sickness knows no boundaries. For the people I study, what mattered was the response to sickness and finding a duty—rooted in faith, reason, and experience—to alleviate suffering.

Today, we continue to rely on multiple sources of duty and the language of duty when we choose to help people: many Americans do have a sense of shared vulnerability grounded in experience. Others rely on our common humanity and sympathy, our religious convictions, our concern for civic cohesion and order, our interest in cleanliness and public health, or our desire for social progress. We haven’t always thought critically about our social duty to provide healthcare, leading to concerns that government has become too paternalistic in providing healthcare. There have been and will be missteps in our pursuit of care, but that doesn’t mean we can’t have a conversation about duty. In fact, that means we should have a conversation. While we may not always agree on the motivating factors, we must recognize the care for others as a common enterprise, to pursue in ways that do not discriminate or harm.

One way we don’t differ greatly from early Americans is in how devastating illness can be. In early America, physical suffering affected every aspect of human life, from economic opportunities and education to family life and gender roles. The defining and far-reaching effects of physical suffering remain today. We have incredible medical research and treatment possibilities, accessible and clean hospitals, and trained medical practitioners. Yet people still suffer, and sometimes they suffer because they are unable to access affordable healthcare or are forced to make difficult decisions between health and debt. As in early America, ill-health today can define your life: your career, your identity, your opportunities.

Health is essential to full participation in civil society; this was a major impetus for Medicare and Medicaid legislation. These programs, alongside medical developments, have made possible wide-scale alleviation of suffering in ways that would have been unimaginable to early Americans. When Lyndon Johnson signed Medicare into law in 1965, however, his rhetoric recognized antecedents. He praised his predecessor Harry Truman, “who planted the seeds of compassion and duty which have today flowered into care for the sick, and serenity for the fearful.”

Medicare and Medicaid were born from compassion and duty, from “the piercing and humane eye which can see beyond the words to the people that they touch.” Johnson’s words came from a history of enlightened humanitarianism, from lived experience, and, finally, from scripture. He quoted Deuteronomy 15:11, explaining that the tradition to care “is as old as the day it was first commanded: ‘Thou shalt open thine hand wide unto thy brother, to thy poor, to thy needy, in thy land.’”

Remembering that early Americans approached healthcare as a duty to others, grounded in diverse sources, doesn’t provide easy answers for our present moment. But it does offer an avenue for progress in healthcare debates: most Americans today still feel some duty—even if our sources are ever-more diverse. The current conversation is expanded and deepened when we think about this duty alongside rights, and such reframing also offers new resources for persuasion in calls for fuller coverage. It helps balance the story, reminding us of what is, after all, a crucial part of the health/care equation: the care of the community for the health of all.

When I initially wrote this essay in September 2017, we were in a conversation about the fate of the Affordable Care Act. Three years later, we are still having that conversation. The Supreme Court on Monday agreed to hear arguments regarding the constitutionality of the ACA and, in particular, the individual mandate.

We are also in the middle of a campaign primary season where the ACA faces competing ideas like Medicare-for-all—an idea that for both Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren is grounded in a conviction that healthcare is a human right.

But perhaps the most interesting current event for reconsidering public health is the wide-scale anxiety surrounding the COVID-19 outbreak and the concerns it raises not only for the US healthcare system but also for the US and global economies. The peculiar system of healthcare in the United States has raised fears that, faced with potentially steep medical bills and little-to-no sick leave, some Americans will not seek testing or treatment, allowing the disease to spread further and faster.

It remains to be seen how COVID-19 will spread or resolve, but it is nonetheless an important reminder that on the other side of the human right to healthcare remains the fundamental question of duty. Nothing is more likely to remind us of a society’s duty to provide basic and universal healthcare than an epidemic for which there is (as yet) no vaccine and to which we are all susceptible, regardless of our current health and wealth.

As political, religious, and medical leaders have responded, we see calls to duty. Coronavirus calls us to act with responsibility to fellow worshippers, patients, and citizens. Once the virus is effectively contained, we would do well to remember and expand this conversation of duty from the realm of immediate concern and to recognize the social, economic, and civil good of widely-accessible healthcare in our everyday lives. ♦

Further Reading

Elaine Forman Crane, “‘I Have Suffer’d Much Today’: The Defining Force of Pain in Early America,” in Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America, ed. Ronald Hoffman, Mechal Sobel, and Fredrika J. Teute (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997): 370-403.

Philippa Koch, “Experience and the Soul in Eighteenth-Century Medicine,” Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 85 (September 2016): 552-586.

Editor’s Note: This essay is adapted from an earlier version published by the Religion & Culture Forum, the Marty Center's other digital publication.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.

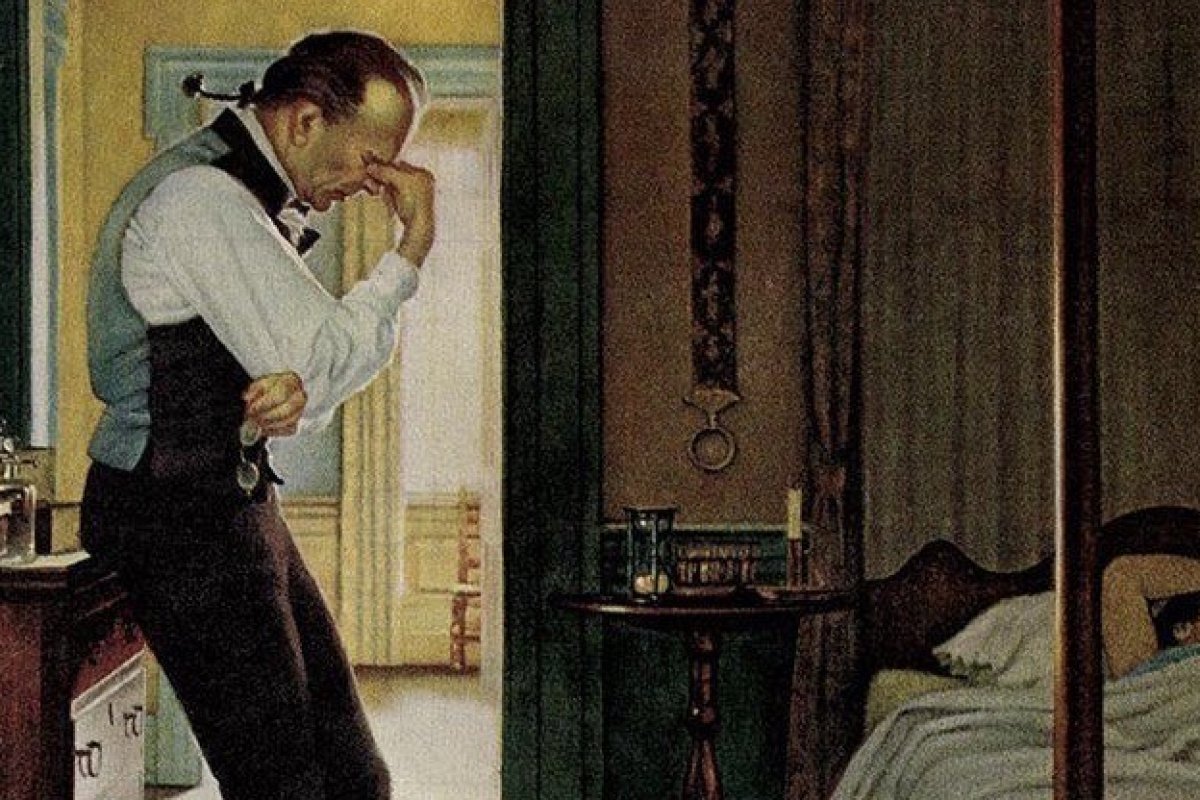

Feature Image: Robert A. Thom, “Benjamin Rush: Physician, Pedant, Patriot,” 1959.