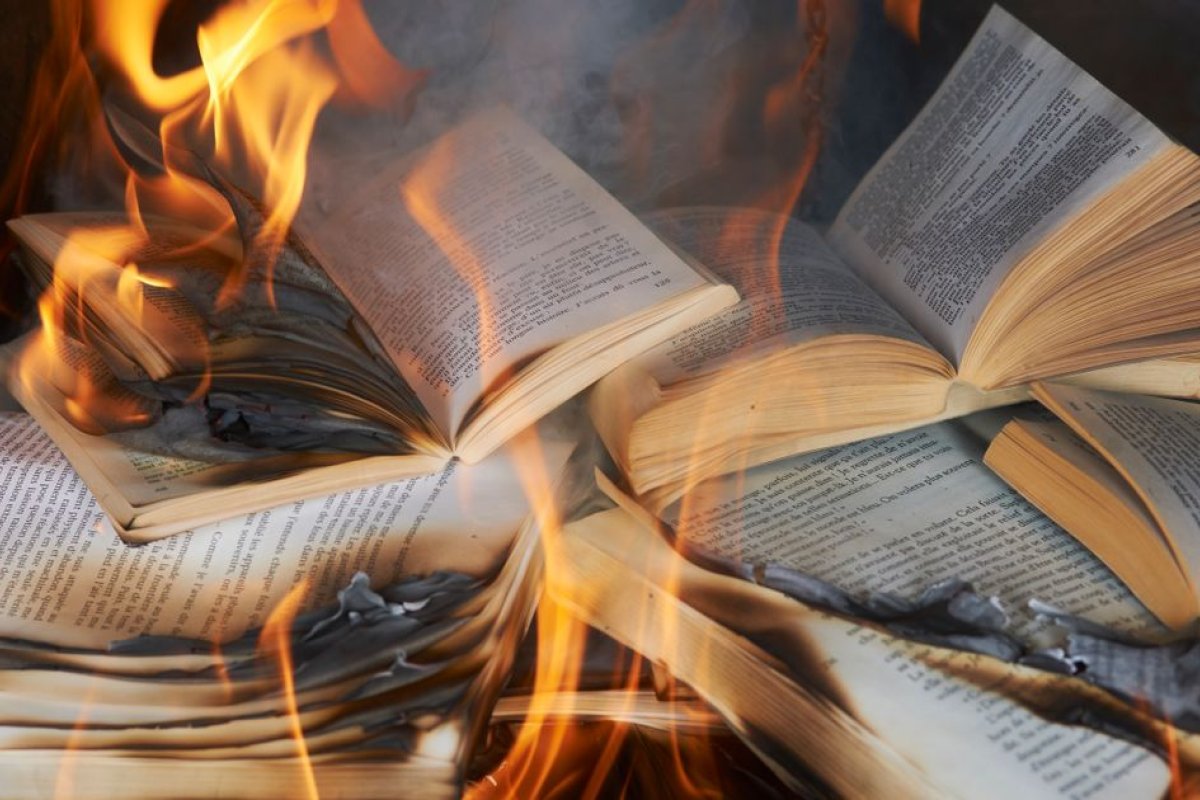

Fahrenheit 451 Redux: Free Thinking in the Present?

Enough with champions of the right and the left, the book burners and those of cancel culture: the present moment calls for a few more firemen like Ray Bradbury.

§1 The Fireman's Work

In 1953 Ray Bradbury published what is perhaps his best novel, Fahrenheit 451. Recall that the title comes from the temperature needed to ignite and burn paper. In this dystopia, American society is depicted as reduced to hedonism and the scorning of intellectuals for the sake of state control of citizens. The government has set up a program of banning and burning books and even the houses where they are found. The main character, Guy Montag, is a "Fireman," that is, one of the agents appointed to burn books. While he goes through something of a conversion, the impulse behind the government's program is that books with offensive or difficult language undermine the state’s leveling of society and make people feel bad.

The details of the novel are not the subject of this column. What we need to explore is the anxiety and perplexity that are driving today’s cultural and social conflicts. So, like the book this column is an exercise in social and cultural interpretation and criticism. Bradbury noted in various interviews that he wrote the book amid the McCarthy era, and so the suppression of supposed "communists," and he was motivated to write the book by a worry that mass media was destroying literacy. Today we hear similar chants against "socialism" and "socialists" even as the influence of social media spreads and the attention span of Americans seems reduced to nil. Bradbury’s alarming prescience about the fate of "elites" amidst the rule of fake news and cancel culture acts as a mirror for our present anxiety, where how people feel about themselves is fueling the drive to ban and even burn books.[1] Such anxiety is easily manipulated for political purposes.

Our current social and cultural landscape is clearly in need of some decoding. Let's start with what is happening on the ground and then interrogate the deeper forces at work in this dangerous moment. We'll find, surprisingly, the attack on free thinking answered by a religious inversion of that impulse. Some anxieties and some perplexities, it turns out, are crucial for advancing a free society.

§2 Parental Misgivings

The current round of calls for banning and burning books was ignited by the recent Virginia governor’s race. Glenn Youngkin (R), the eventual winner, chastised former governor Terry McAuliffe (D), for vetoing a bill that allowed parents to opt their children out from reading texts deemed too explicit. The backlash against McAuliffe’s liberal stance, as the Washington Post noted in a recent story, targeted a "famous book from Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, Beloved, about an enslaved Black woman who kills her 2-year-old daughter to prevent her from being enslaved herself."[2]

The latest controversy to get sensitive white parents in an anxious tizzy is a subject not actually taught in public schools, that is, "Critical Race Theory." The charge is that CRT (we all need acronyms--saves time and thinking!) teaches white kids to hate their dear selves and these glorious and non-racist United States. CRT supposedly throws students into perplexity about the history of race in this country, and so the identity of people. Yet the anxiety and perplexity about one's identity are not only an obsession of the "Right." Consider the conscience of a "woke” culture that too often seems unwilling to engage in argument with those deemed unworthy of even being heard. Cancel culture, ironically, is also driven by anxiety about identity and a fear of perplexity. It too is a quest for being right and having clear cut answers and convictions.

Let's be clear. I am not suggesting a false equivalence between cancel culture and some of the legitimation of violent repression that happens on the right. Not at all. At issue is that in the present moment thinking about ourselves and this nation’s history seems to be driven by different shades of anxiety about one's identity and moral rectitude.

What then is my point? The Firemen are returning, or so it seems. In the same Washington Post article, it was noted that following the election in Virginia, some school board members proposed burning books thought to be sexually explicit. Meanwhile, as widely reported, Texas State Rep. Matt Krause has asked schools if any of 850 books are in their school libraries and classrooms. As Bradbury knows, the driving impulse behind burning is how books make people "feel." That feeling, I am suggesting, is the desire to escape any anxiety about one's identity and a fear of perplexity about the state of our nation and its history. Yet that feeling is also what makes people open to political manipulation, a fact made obvious in recent raucous school board meetings.

What seems to be at issue, if we interrogate the current anxiety a bit further, is the volatility of such feelings, insofar as they supply the motivation that drives book burners, the Firemen, and the vanguard of woke culture. What do I mean?

§3 The Ashes of Liberty

When judgments about education are driven by anxiety and repulsion to perplexity, a culture must look out. I am not simply noting the burning of books by the Nazis or in the Reformation period the torching of Martin Luther's writings or even the many bonfires of knowledge and human expression that scar our civilization's history. (Although, to be honest those would be good to explore!) What remains obscured and hard to untangle in the current cultural conflagration is, it seems, the essential yet vulnerable nature of learning. It is, sadly, what got Socrates, wandering the streets of ancient Athens, sent to trial, and poisoned by the city.

In the so-called early dialogues, Plato shows us how Socrates provokes his interlocutors into perplexity or puzzlement (aporia) about accepted knowledge. His purpose is to question the validity and understanding of accepted beliefs and engage in a constant search for truth through love of wisdom. By relentless cross examination, the elenchos, one is hopefully moved to interrogate the puzzle--and one's anxiety about it! --in order to clean up confusions, wipe out illusions, and come to some tentative resolution. Granted most of those early dialogues leave the speakers in an aporia. Some must have thought that Socrates was gaslighting them, making them doubt their perceptions of reality.

Nevertheless, perplexity is what fuels inquiry and the discovery of truths worth living by. For Socrates, wisdom begins with wonder in the face of perplexity, especially about how rightly to live.[3] Alas, current cancel culture and the league of Firemen are at root trying to douse wonder and save us from perplexity, because perplexity can make us "feel" bad, anxious about ourselves and the rightness of our lives. Of course, something like that sentiment led to the sentence of hemlock for Socrates.

One needs to see what is really at stake in education by perplexity. What the so-called Socratic method sought to provoke was curiosity and a willingness to question accepted beliefs, including beliefs about the gods, the glory of one's culture, and the moral goodness of one's dear self. The current rush to submit books and argument to Fahrenheit 451 is nothing less than an attack on curiosity and the demand for critical self-awareness under shared standards of truth. No wonder that forces emerge which seek political and social control by attacking what they call fake news and politically incorrect opinions. In the end, liberty will lay in ashes. It is liberty itself that is under fire, the liberty of thinking. Without the free exchange and competition between ideas, how are we to face freely our perplexities and attain, at least for the moment, solid convictions for the orientation of life?

However, the question becomes, what is the right kind or form of perplexity that can and should energize the quest for truth and wisdom?

§4 The Divine Fire of the Mind

Having moved through layers of reflection, we reach, at last, a sighting of religion in this vexing and dangerous societal moment. The image of fire is a complex one in the world's religions. Flaming Seraphim, the Burning Bush, the Holy Spirit, tongues of fire dancing on the head of disciples, the fires of Hell (Jahannam in Islam), the fires of desire in Buddhism, and on and on. In this instance, we can see that one crucial meaning, religiously speaking, of the image of fire is purification, not only purgatory (in Dante and medieval Christian theology) but also the purifying of the mind.

Bearing this out, the religious insight presents us with an inverse meaning from the call to burn books. That call leaves folks secure in their state of cultural bias (America is, after all, the greatest nation, right?) or the conceit to assume that one has the right answers, the right values. By contrast, the religions know that all true learning is, at its deepest, not simply acquiring information, but rather a purifying of mind and shaping of character. What this nation needs now is a willingness to face perplexity and anxiety in order thereby to seek the truth about our history. Only then will we chasten our conceits and begin to purge the layers of racism that seam our history.

Enough with champions of the right and the left, the book burners and those of cancel culture. The present moment calls for a few more firemen like Ray Bradbury who are willing to light up our actual condition. Maybe more of us need to follow Socrates and dare to be perplexed and so open to new ways of thinking and living. At stake, in the end, is the possibility of free and truthful existence, as well as of peaceful coexistence among us.

[1] See the opinion piece by Michelle Goldberg, "A Frenzy of Book Banning" https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/12/opinion/book-bans.html.

[2] https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/11/10/i-think-we-should-throw-those-books-fire-movement-builds-right-target-books/

[3] See Gregory Vlastos, Socrates, Ironist and Moral Philosopher (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991).

Photo: Via creative commons.

Sightings is a publication of the Martin Marty Center for the Public Understanding of Religion at the University of Chicago Divinity School and is edited by Alireza Doostdar and Willemien Otten. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editors.