Niebuhr and the Situation

Millennials are often accused of whatever particular accusers want to assign to their victims of choice

Millennials are often accused of whatever particular accusers want to assign to their victims of choice. One charge, among so many others, is that they do not know or care about history. Teachers of undergraduates note how frequently they find their students unable to relate to people and events of the past, even the relatively recent past. These students may know about George Washington or, currently, Alexander Hamilton, but otherwise draw a blank when it comes to national figures. Even celebrities are relegated to the Gallery of the Forgotten after a generation or so.

Millennials are often accused of whatever particular accusers want to assign to their victims of choice. One charge, among so many others, is that they do not know or care about history. Teachers of undergraduates note how frequently they find their students unable to relate to people and events of the past, even the relatively recent past. These students may know about George Washington or, currently, Alexander Hamilton, but otherwise draw a blank when it comes to national figures. Even celebrities are relegated to the Gallery of the Forgotten after a generation or so.

Rather than preach a homily of lamentation over this reality, let me focus on an instance from the world of religion and theology: the case of Reinhold Niebuhr, the Protestant theologian who towered over the past mid-century. Prompted by advertising for a local advance screening of a fine film directed by Martin Doblmeier; a companion book, An American Conscience, by Jeremy L. Sabella; and reports from a variety of conferences and colloquies inspired by the film, I viewed it the other evening. I also learned from a panel discussion following the screening, and had a chance to chat with fellow observers representing various generations. It is difficult not to be swept up in the Niebuhr story, and I confess to having been swept up in it again.

Listening in and reading much about this genius, a shaper in religion and politics, one encounters a constant question: “Where are the Niebuhrs today?” (There were several Niebuhrs “yesterday,” in addition to Reinhold: brother and fellow theologian H. Richard; sister [educator] Hulda; wife [professor] Ursula; nephew, the recently deceased Richard Reinhold; etc.—all of note in their time.) The question inspires realists (Niebuhr was one) and pessimists (Niebuhr was not one) not to wax nostalgic, but to engage in an assessment of our society and culture, in particular with respect to Moral Man and Immoral Society, The Nature and Destiny of Man, The Irony of American History, and other themes reflected in Niebuhrian book titles.

The vocational category that fits Niebuhr best, I think, is “public theologian,” which is what I called him in a 1974 article on the basis of which I am credited with (or blamed for) inventing the “public theology” category. (The ghost of Niebuhr whispers: “Be careful, ‘inventor’ M.E.M., haven’t you read me on the sin of pride?”) As a public theologian, Niebuhr was excluded from the categories of “systematic” or “biblical” or “practical” theologians. He did draw on the work of such colleagues, as they drew upon him, but he followed his own path: first as a pastor in Detroit, then as professor at Union Theological Seminary, author of profound books, and tirelessly traveling preacher, lecturer, and participant in statecraft and international affairs from the Great Depression to the Cold War.

The most promising response would be for those inspired by the film, as well as by old and new books by and about Niebuhr, not to ask “Who are the new Niebuhrs?” or “Why are there no new Niebuhrs?” We should be concerned less with who he was than with what he did. Exploring the latter may suggest new ways forward for the current generation. Let me offer my own, prompted by a phrase from the late theologian Martin Heinecken, who pointed to the outsider Good Samaritan in Jesus’ famous parable. The Samaritan was pronounced “good,” as a passer-by priest and Levite were not. Heinecken observes: “Did the Samaritan take that poor victim, strapped to his ass like a captive audience, and hand him a tract or preach a sermon? No, he did what the situation demanded, and that was good.” (Emphasis mine, and I do mean to emphasize it.) Niebuhr, anchored as he was in profound biblical witness, also had the Courage to Change, the title of a biography of him snatched from his famed “Serenity Prayer.” But note that as Niebuhr read the situation, he served best in his calling through the writing and publishing of book-length tracts and memorable sermons.

Today’s ethicists, theologians, philosophers, columnists, and ordinary-and-extraordinary citizens all seek to find their way in the midst of our current chaos and anarchy, to “assess what the situation demands,” and begin to address it. If they are Niebuhrian realists, they will not fall into despair or take refuge in nostalgia. Instead, each of these serves best—Niebuhr and Heinecken would both agree—if they would identify and do what the situation demands. In other words, act.

Resources

- Doblmeier, Martin. An American Conscience: The Reinhold Niebuhr Story (2017). See the film’s official website for broadcast dates and screening events.

- Marty, Martin E. “Reinhold Niebuhr: Public Theology and the American Experience,” Journal of Religion, Vol. 54, No. 4 (October 1974), 332-359; reprinted as “Interpretation: The Classic Public Theologian,” in Religion and Republic: The American Circumstance (Beacon, 1987), chapter five.

- Sabella, Jeremy L. An American Conscience: The Reinhold Niebuhr Story—A Companion to the Film by Martin Doblmeier (Eerdmans, 2017).

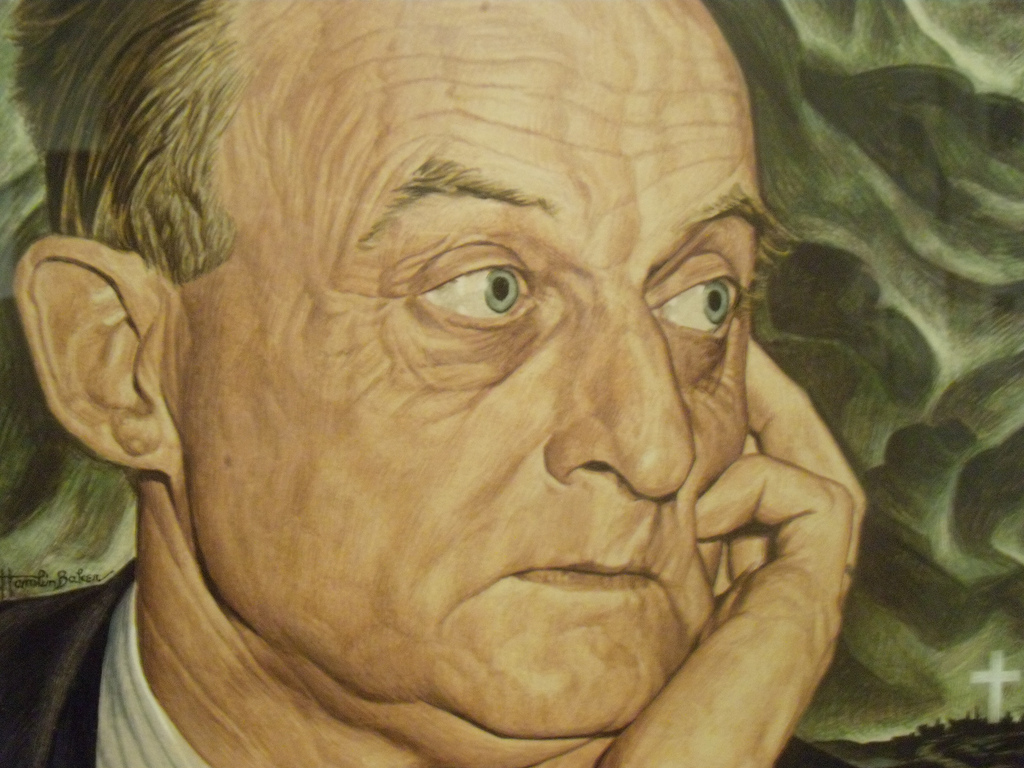

Image: Portrait of Reinhold Niebuhr by Ernest Hamlin Baker | Photo Credit: Wayne Stratz via Flickr (cc)

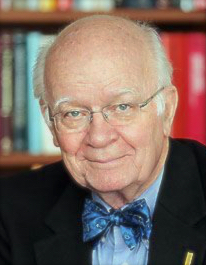

Author, Martin E. Marty, is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. Author, Martin E. Marty, is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco, a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Subscribe to receive Sightings in your inbox twice a week. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.