The Strange War on COVID-19

William James and the potential benefits of “war” analogies for fighting COVID-19

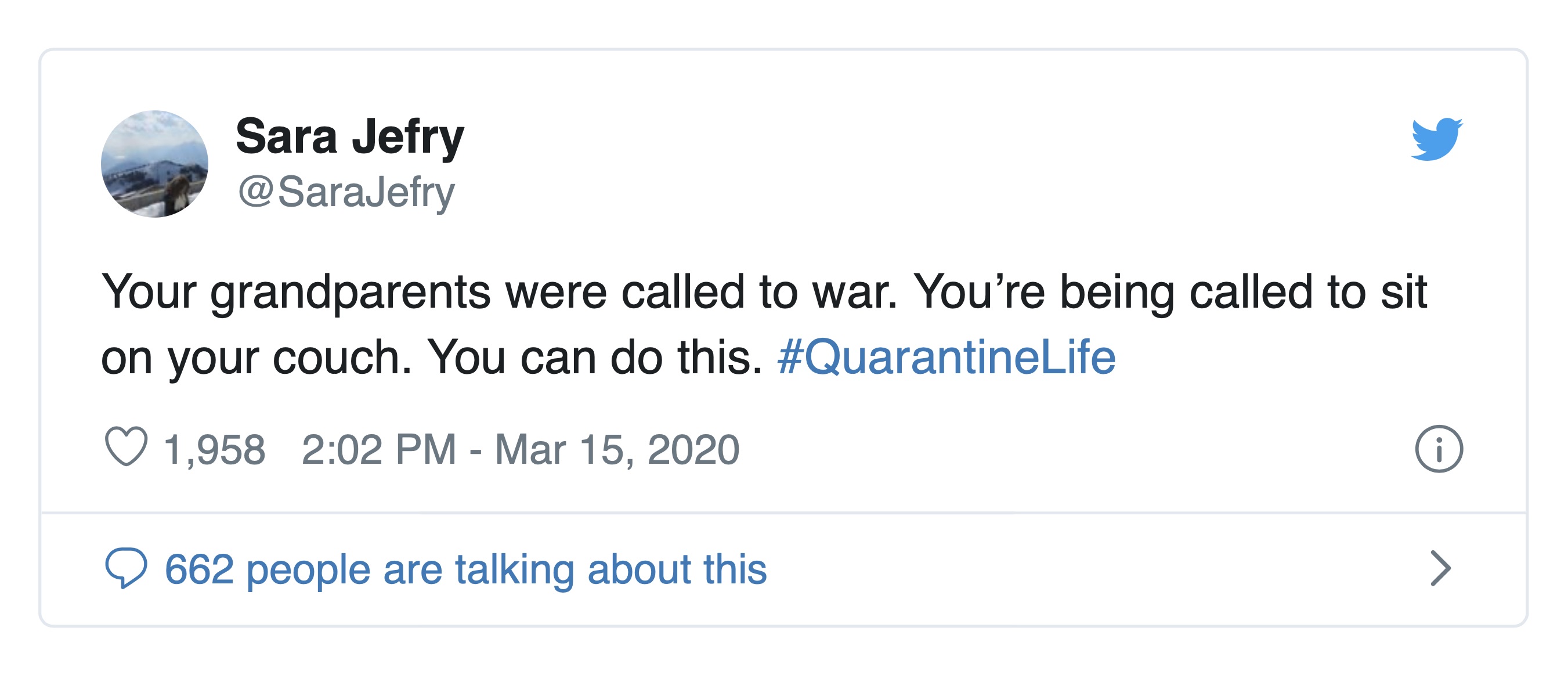

This tweet by Sara Jefry expresses the curious mix of feelings many people have about the current quarantine. In a recent Sightings post, Evan Kuehn described the feeling as both monumental and banal. On the one hand, in terms of its global scale, uncertainty, and significance, this event is comparable to the world wars of the last century. On the other hand, I’m just sitting at home playing video games in my activewear.

So is the comparison to war a fair one? President Trump, for one, has increasingly used the language of war to frame the struggle against COVID-19, saying “We’re at war. In a true sense we’re at war, and we’re fighting an invisible enemy.” He added, “To this day, nobody has seen anything like what they were able to do during World War II. Now it’s our time. We must sacrifice together because we are all in this together and we’ll come through together.” This rhetoric is admittedly a departure from President Trump’s earlier assessment, and more recently he’s downplayed the longevity of the threat, saying (as is often erroneously said about wars) that he expects “complete victory” in a few short weeks. There’s a lot about his handling of the crisis that deserves criticism, but does he have a point about the similarities between the sacrifices needed during wartime and those needed during quarantine?

In an effort to answer this question, we can find some help by turning to American philosopher William James’s now-famous 1910 essay “The Moral Equivalent of War.” Though James was a pacifist, he argued that war has a distinct ability to capture our imaginations and motivate us to collective action. Wars recur throughout history in part because humans long for the drama and romance of war. War enables us to satisfy our deep desires to invest ourselves in something bigger, to work together with others in a shared effort, and to stare down death.

Nations go to war for conquest, for security, for profit, and for a host of other reasons, but among these reasons is because war is captivating. Though wars are not the only situations that push humans to the brink, we are drawn to war for the same reason we are drawn to thrilling stories. War, James writes, possesses an intrinsic aesthetic appeal.

At least in the popular imagination, war calls forth the highest capabilities within us—"fidelity, cohesiveness, tenacity, heroism, conscience, education, inventiveness, economy, wealth, physical health and vigor.” Herein lies war’s intrinsic moral appeal. Though the old U.S. Army slogan “Be all that you can be” was coined after James’s time, he would insist that the desire to be all that we can be is why we find war so irresistible even in spite of its horrors.

James urged his fellow pacifists not to underestimate the aesthetic and moral appeal of warfare. “I do not believe,” he writes, “that peace either ought to be or will be permanent on this globe, unless the states pacifically organized preserve some of the old elements of army-discipline.” Libertarian individualism that demands nothing from the citizen, equitable socialism that does not challenge us to gain virtue through hardship, and a false comfort that insulates us from the struggle for survival—none of these will last because none can satisfy our primal desires.

Rather than trying to suppress the human desire for zealous collective action, James argues, we should try to channel the moral and aesthetic power of war to more constructive ends. Thus, James called for conscripting young people into an army “against Nature”—that is, engage people in a program for farming, window-washing, treating illnesses, and in other ways making the world more hospitable. This shared service would satisfy the moral and aesthetic yearnings war promises to fulfill while also reminding the “luxurious classes” of the struggle for survival that humanity must undertake. James’s essay ultimately inspired the creation of the Peace Corps in the 1960s, and Jimmy Carter cited it in his 1977 plea for a commitment to engaged environmentalism.

With James’s analysis in mind, we can more fully appreciate how efforts at flattening the curve are part of “a war... against an invisible enemy.” The quarantine is not a fearful response to an unknown danger, but a massive collective action to protect the most at-risk people. We should go about it with a similar moral and aesthetic passion which previous generations have gone about war and civilian service. We are now all challenged to do what we can to buy time for the medical workers on the proverbial front lines. The quarantine can, and arguably should, be understood as an act of global solidarity that demands discipline and sacrifice, and strange as it may sound, we should feel proud to participate in it. This moment is an opportunity for people to work together precisely by being apart, for people to do something significant precisely by doing nothing.

We should not press the analogy too far, and admittedly playing Call of Duty has very little to do with modern warfare. But James’s article encourages us to see the struggle against COVID-19 not only as something we all hope to survive, but as an opportunity for humanity to triumph together over a deadly foe. ♦

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.

Image: South Korean self-defense forces on the front lines against COVID-19.