Redefining the American Civil Religion

Editor's note. This is the third in a series of essays on the Trump phenomenon—or "Trumpism," if such a thing can be defined—and what it reveals about the relationship between religion and politics in America today

Editor's note. This is the third in a series of essays on the Trump phenomenon—or "Trumpism," if such a thing can be defined—and what it reveals about the relationship between religion and politics in America today. Be sure to check out the previous essays by Roger Griffin and Landon Schnabel, and look for one final installment from Sightings before the U.S. presidential election.

One of the more interesting elements of the contemporary American political scene is its rhetorical exaggeration. Admittedly, there is a long history of American mudslinging, as when in 1848, presidential candidate Lewis Cass was termed a “pot-bellied, mutton-headed cucumber,” or when, a bit earlier yet, John Adams was accused of having a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman." Immodest exaggeration has always been part of politics, American or otherwise.

One of the more interesting elements of the contemporary American political scene is its rhetorical exaggeration. Admittedly, there is a long history of American mudslinging, as when in 1848, presidential candidate Lewis Cass was termed a “pot-bellied, mutton-headed cucumber,” or when, a bit earlier yet, John Adams was accused of having a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman." Immodest exaggeration has always been part of politics, American or otherwise.

However, contemporary national political rhetoric, especially from the presidential candidates, is more ferocious than in any recent memory. Much of this proceeds from conflation. Hence a is associated with x, x may be associated with y, and y being vaguely close to z, means that a = z. Now rationally, we know or can easily find out that a ≠ z, but once the claim has been repeated, it has subconscious power not easily dismissed. Thus Donald Trump is a “fascist,” while Hillary Clinton is frequently termed “Hitlery” in countless comments sections, to give two typical instances of reductio ad Hitlerum.

Why the rhetorical ferocity? We are witnessing a battle over what we might term the American civil religion. Each side in this battle seeks to capture the moral high ground.

For the past forty years or so, the moral high ground was reliably held by what we may term the egalitarians. This is true of both Republicans and Democrats; Democrats of course had the rhetorical advantage for the most part, but Republicans often would counter with the claim that they are the true egalitarians. Each side would ally itself with whatever historical figure—Lincoln, MLK—seemed to serve best as a rhetorical saint for the different sects of this egalitarian civil religion.

But what is happening today is really dramatic because the current civil religion, long since accepted at least with mumbled requisite expressions of piety, oftener with more flamboyant expressions of moral signaling—see how virtuous I am, how egalitarian—shows fissures. Its adherents have become louder, more extreme, sometimes even violent. Certainly rhetorical violence is more common.

And at the same time, growing numbers of Americans find themselves not truly believers. Perhaps this is because the rhetoric of moral egalitarian progress has been accompanied with a continuing decline in American prosperity, especially for the middle class and the poor. Perhaps too, received truths can only be received for so long before some begin to question them.

Whatever the reasons, the first national political candidate to call into question the current American civil religion was Donald J. Trump, who said, “I don’t frankly have time for total political correctness. And to be honest with you, this country doesn’t have time either.” And in his acceptance of the Republican nomination, he said, “We cannot afford to be so politically correct anymore.” The importance of such remarks, from a presidential candidate, can hardly be overstated. Because seen in the light of the reigning American civil religion, this was nothing less than a rallying cry to the critics or, if you like, heretics who no longer believe.

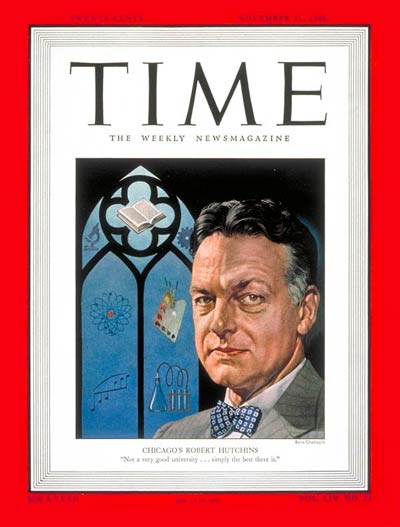

And what would another American civil religion look like? Without doubt, it would hark back to earlier American traditions that—as that remarkable leader of the University of Chicago, Robert Maynard Hutchins did so well—celebrate and encourage individual and shared cultural achievements. Such a figure extolled free intellectual discourse, not suppression of speech, let alone mandates for equality of results. Perception that the latter is in the ascendant is what drives remarks like Trump’s, and the sentiments of those to whom he is no doubt appealing.

The speech by Hillary Clinton in late August 2016, attacking the “Alternative Right” or “alt-right,” served to highlight that nascent pro-white political movement and provide it considerable publicity. Of course, it is doubtful whether there is much to directly link Trump and the Alternative Right, but they do share disdain for much contemporary egalitarian political correctness.

In the context of what I am terming the American civil religion, the Alternative Right movement and the presidential candidacy of Donald J. Trump both should be seen not only as significant political developments in themselves, but also perhaps as indicators of a still larger movement whose full dimensions are not yet visible, but that may redefine the American civil religion for generations to come. After all, a pendulum does not swing only in one direction.

Image: Cover of TIME Magazine, Vol. LIV, No. 21 (November 21, 1949), with caption, "Chicago's Robert Hutchins: 'Not a very good university... simply the best there is.'"

Author, Arthur Versluis, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at Michigan State University. His work focuses on the intersections of religion, literature, and social science. Editor of JSR: Journal for the Study of Radicalism, he is author of many books, including American Gurus: From Transcendentalism to New Age Religion (Oxford University Press, 2014), ed., Esotericism, Religion, and Politics (North American Academic Press, 2012), The New Inquisitions (Oxford University Press, 2006), and Restoring Paradise (SUNY Press, 2004). Author, Arthur Versluis, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at Michigan State University. His work focuses on the intersections of religion, literature, and social science. Editor of JSR: Journal for the Study of Radicalism, he is author of many books, including American Gurus: From Transcendentalism to New Age Religion (Oxford University Press, 2014), ed., Esotericism, Religion, and Politics (North American Academic Press, 2012), The New Inquisitions (Oxford University Press, 2006), and Restoring Paradise (SUNY Press, 2004). |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco, a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Click here to subscribe to Sightings as a twice-weekly email. You can also follow us on Twitter.