Raw Religion

This Sightings column is about "religion in the raw," and even the rawest—and most damaging—forms of religion

This Sightings column is about "religion in the raw," and even the rawest—and most damaging—forms of religion. That is because Sightings is keen to catch a glimpse of religion wherever and whenever it appears in public life, and we can’t ignore "raw religion" in news stories over the past few weeks. So, we’ll explore how the combustible relation of sex and religion in this society feeds the transition from religious honesty to litigiousness; how it is at work in the transformation of religious conviction to moral/political division; and, on a lighter note, how sex and religion can take idiosyncratic forms when driven by personal preference. But, first, some background.

This Sightings column is about "religion in the raw," and even the rawest—and most damaging—forms of religion. That is because Sightings is keen to catch a glimpse of religion wherever and whenever it appears in public life, and we can’t ignore "raw religion" in news stories over the past few weeks. So, we’ll explore how the combustible relation of sex and religion in this society feeds the transition from religious honesty to litigiousness; how it is at work in the transformation of religious conviction to moral/political division; and, on a lighter note, how sex and religion can take idiosyncratic forms when driven by personal preference. But, first, some background.

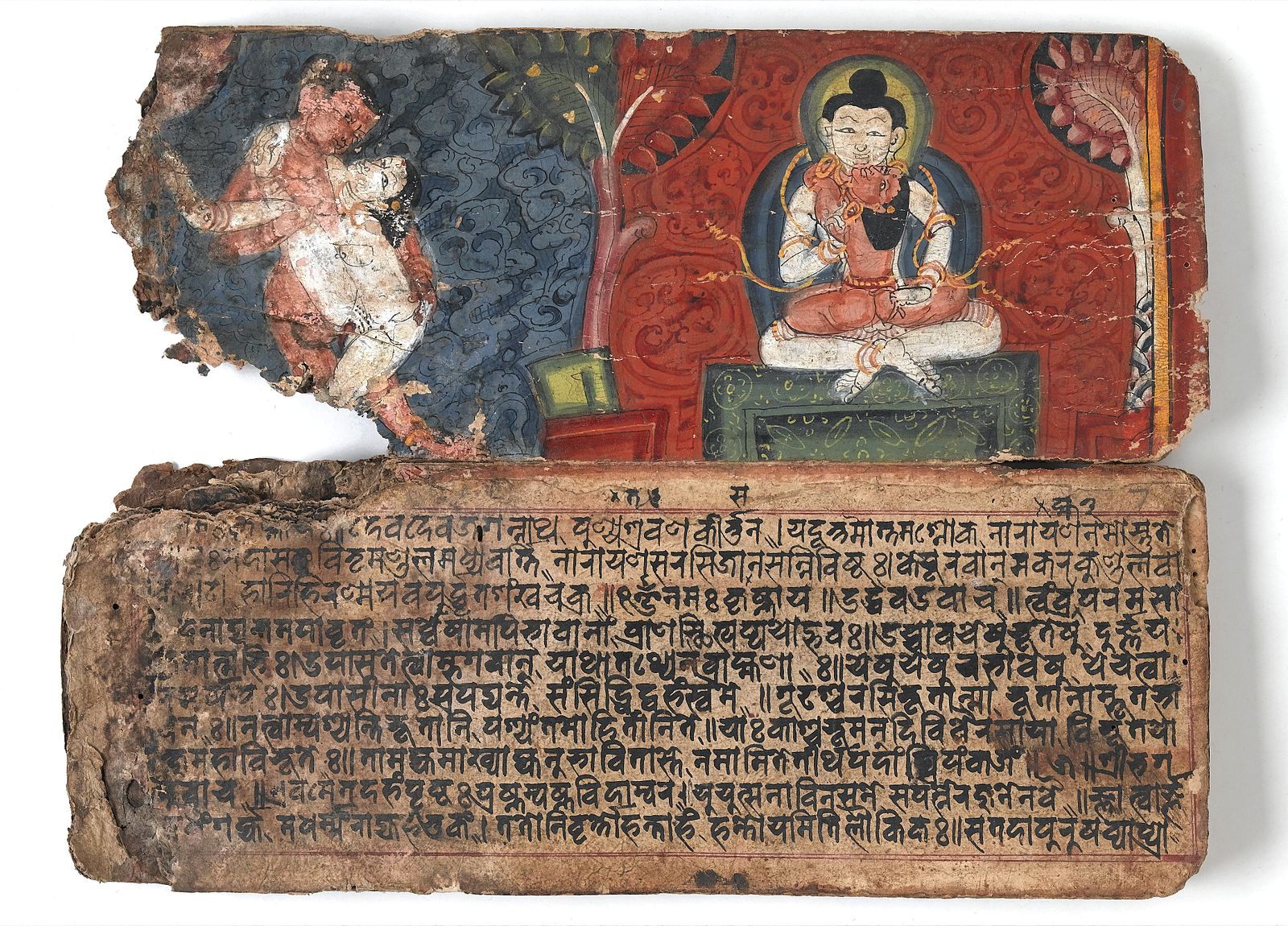

There is, of course, nothing new or even surprising that religion and sex—whether the sex is joyous, tyrannous, hateful, or sacred and the religion ennobling, beautiful, good, or an opiate of the people—traffic together. Ancient stories about the birth of gods, the Garden of Eden, and the creation of the world from goddesses and gods are known, recited, and studied the world over. Religious symbols—say, the sacred lingam as a symbol of divine energy or the pictures and icons of the Virgin Mary as the Mother of God—fill places of worship. Insofar as religion is, in various ways, about life and death such that sex is a marker of our embodied finitude, no one should be surprised by the intimate connection between the two. It is also obvious that religious attitudes differ within and between religions. Attitudes range from St. Augustine’s—who wrote in Soliloquies, 1, “Nothing is so much to be shunned as sex”—to the Kamasutra and its aids to love. All of this is obvious enough and hardly a fact worthy of a Sightings post. So, given the ubiquity and conspicuity of the interplay between religion and sex, why, then, this column?

Sightings is not limited to the appearance of religion qua religion, nor does it seek out only “respectable” religion, but rather it explores disclosures of religion(s) in all public forms and so how religious sentiments and practices saturate a society and its cultural life even as culture and society frame and so shape those appearances. As Paul Tillich—about whom swirls, sadly and tragically, stories that he engaged in sexual misconduct and possible abuse—might put it, there is a “symbolic” relation between the two: culture is the form of religion and religion is its supposed substance. Bracketing the metaphysical pretenses of form and substance, one can still wonder what recent sightings of sex and religion tell us about contemporary American society and how the content of religion is informed and transformed in and by public life.

Three vignettes on the subject: the first, and most horrifying, is about the sex abuse scandal in the Catholic Church and the defrocking by Pope Francis of ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick. According to a report last week on the defrocking by Religion News Service, McCarrick solicited sex while hearing confessions (!) and committed sex crimes against minors and adults for a long period of time. In the most religiously and morally sensitive space—that of a confessional—and with vulnerable children and adults, the power of sex trumped religious rite and vocation. Heaven knows that the victims and survivors of the Cardinal’s abuse have suffered a hell far greater than his defrocking. And just as astonishing is the recent disclosure that the Vatican has rules and guidelines for priests that father children. This revelation precedes by just a few days a meeting of the Pope and Cardinals in Rome to address the scandal and to meet with some victims. But survivors and victims are, horrifically, found everywhere. The scope of sexual abuse within the ranks of the conservative Southern Baptist Convention has been exposed even as the SBC has vowed to address the problem.

We know that sexual abuse is found in virtually every religious tradition. Perhaps—just perhaps—Augustine had a point, at least about the power of sex to drive and disorient our lives. But what these sightings show is not a vindication of Augustine’s judgment, but rather that we live in a society where the most sacred spaces and symbols of religion—the confessional, worship services, counseling sessions, the College of Cardinals, and Church Conventions—conceal the predatory power of sexual drives. And precisely because of this fact, these sightings of “raw religion” transfer judgment from religious communities (or the divine) to legal authorities in a culture zealous for litigation with little trust in religious institutions to carry out justice in these matters. Tragically, civil courts become, then, the forum in which the relation of sex and religion appear, altering the very substance of religion.

The first vignette is then about the litigious informing of religion’s substance in the public around matters of sex. A second vignette: as this column goes to press, a special session of the General Conference of the United Methodist Church is being held in St. Louis, Missouri, February 23-26, to address questions surrounding the marriage, ordination, and recognition of LGBTQ believers. Like other Protestant denominations, the topic has drawn extensive press and media coverage. After all, what could be juicier than sightings of Christians fighting about sex? And like other denominations, the matter is posed to tear asunder the unity of the church. Bishops have proposed different “ways forward” for the church, but contention surrounds each proposal. Anxiety runs throughout the church’s membership about the uncertainty of the future. Yet, here we see the power of sex to inform religious conviction through cultural means. In a nation riven with culture wars and in a state of extreme political division, why not the churches as well? In the attempt to proclaim a seemingly countercultural message of forgiveness, what appears in public life are the same cultural conflicts simply robed in religious garb. Rather than transforming the culture—as Methodists like to think they do (and I know this as a lifelong member)—the reality is that cultural forms are supplanting religious substance.

Now, a third vignette, more fetching and more in the spirit of the Kamasutra than the other two. In a recent New York Times article by Hilary Sheinbaum titled “And the Bride Wore, Um, Nothing (the Groom, Too),” we are told of the lovely romances and weddings held at Nudist Resorts, often enough in an Edenic spirit. The couples—ranging in age from twenty to sixty years old—talk about their chosen lifestyle, what it means to them. Ms. Carolyn Hawkins, seventy-five years old, we are told performs the ceremonies, and, according to Sheinbaum, dresses up or down as deemed fitting. Weddings are extremely widespread human rituals—maybe even universal in scope—and, admittedly, they are not necessarily religious in nature. And the point of this sighting is not voyeuristic or puritanical! The point is that we live in a society where dreams of innocence and personal preference inform rites and rituals that, traditionally, were more about orienting life and even educating the sex drive, as the Kamasutra has it, than assuming its relative benign, gentle, and morally empty nature. One could say, in approval or condemnation, that this shift is just the product of the so-called sexual revolution. But whatever its origin, at issue here is, again, a shift in substance or content through a shift in the cultural informing of religious practices.

Despite the constant presence of religion in American public life and its sightings within virtually every sphere of human experience, we live in a time when the courts, cultural and political divisions, and preferences for personal innocence are informing religion to the point of becoming its substance. We should ponder long and hard about the social power of sex and culture within the vacuity of American religions.

Author, William Schweiker (PhD’85), is the Edward L. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of Theological Ethics at the Divinity School. Author, William Schweiker (PhD’85), is the Edward L. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of Theological Ethics at the Divinity School. |

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD student in Religions in America at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.