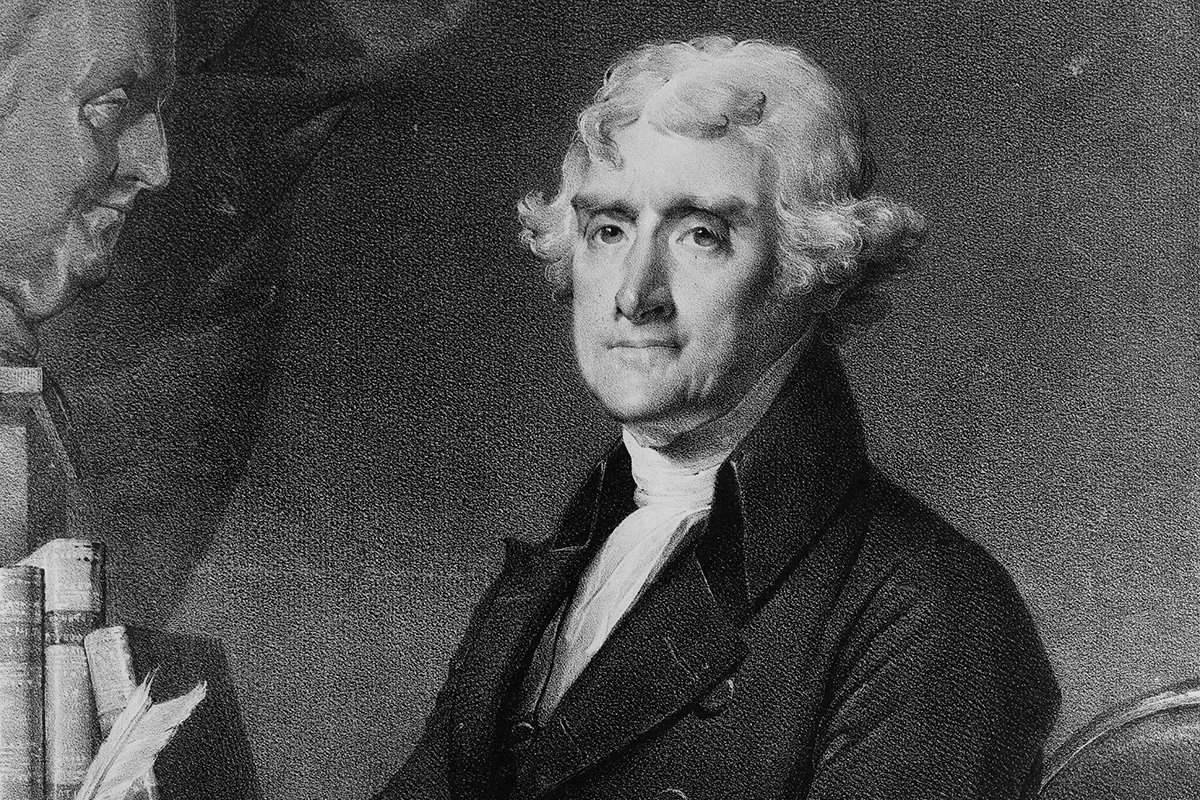

Enlightenment Religion in the Private and Public Bibles of Thomas Jefferson

For Thomas Jefferson, the human being's responsibility was to extricate and celebrate good religion.

By Richard A. RosengartenFebruary 29, 2024

Teaching a course on the history of religion in the Enlightenment is one of the great pedagogical challenges: there is no shortage of terrific material, and at the same time no shortage of confidence (shared by scholars young and old alike) about what to make of it. The tension I invariably feel in putting together the syllabus is somewhat eased as we begin to read and to discuss, and everyone discovers that religion in the Enlightenment is not quite what they anticipated. Whether it is the Anglican divine Richard Hooker or the Scottish skeptic David Hume, the caustic humanist Thomas Hobbes or the sly scriptural deconstructionist Baruch Spinoza, each author’s understanding of religion is invariably subtler, and defiant of preconception, than anticipated.

An outstanding example of this subtlety is the history and afterlife of “Thomas Jefferson’s Bible.” Like many Enlightenment texts, this may seem familiar, and yet there is more to it than is often presupposed. An avid reader of the Bible and a collector of Bibles, Jefferson quickly became skeptical and even dismissive of its accounts of supernatural activity: miracles, divine “interventions,” and the bodily resurrection of Jesus. But he nonetheless continued to read. Despite these reservations, he judged that the moral teachings of Jesus are – a word he uses constantly in his correspondence – “sublime”: the greatest ethical code known to him. Jefferson’s summary formulation of this in a letter to John Adams is that the inestimable “diamonds” of Jesus’s moral teachings had been submerged in the “dunghill” of the New Testament narratives and their corrupting exegesis by the Christian churches.

What was to be done about the discovery of good religion and bad religion in the same book? Jefferson’s initial foray toward his answer was what he called “The Syllabus,” a project to establish a “Philosophy of Jesus” for his own personal reference. This involved comparison of Latin, Greek, French, and English versions of the Gospels – along with a sharp razor and some glue. Jefferson extracted the sublime moral teachings and discarded the narrative dung, pasting together the former into a continuous new document. He titled an initial version – which we do not have – The Philosophy of Jesus. Evidence that he continued to experiment with this is that he eventually recomposed it as The Life and Morals of Jesus, which we do have – he bound it in leather circa 1820.

There are abundant lessons about Enlightenment religion in Jefferson’s handiwork. On the one hand, Jefferson’s “Bible” is only the New Testament, and indeed solely the Gospels within the New Testament. It is not “the Bible” in any sense that either Jews or Christians would recognize. However learned and intentional, it is bowdlerized. At the same time one would be hard-pressed not to recognize in Jefferson’s sustained, considered, meticulous efforts a real reverence for the moral teachings of Jesus. We see, up close and very personally, that there is for Jefferson good and bad religion. They can be distinguished, and the human being’s responsibility is to extricate and then to celebrate the good.

This is not so far afield from classic biblical exegesis as we may tend to think. As is well known, the history of such exegesis is studded with instances of the propensity, bordering on necessity, to articulate a “canon within the canon” of a revelatory book that seems in contradiction with itself. It is at least arguable that Jefferson is simply using blunt tools to do what Martin Luther did with equally blunt theological doctrine when he dismissed the Epistle of James as “straw” and commended its removal from the New Testament. Galatians was good religion, James bad.

This points to a second, crucial aspect of Enlightenment religion as represented by “Jefferson’s Bible”: The Life and Morals of Jesus was never intended for public reading. His compilation was only published, and then for private circulation (with some miracles re-inserted) at the behest of some members of Congress in 1902. What was termed “The Thomas Jefferson Bible” was first published in 1921, just less than a century following his death. These editions made public a private document, and in making it public, can serve to misconstrue both its purpose and its author’s attitudes about private religion and public life. The reinsertion of miracles into the published version, and the change of title, underscore the distortions that are ready at hand in such a process.

Jefferson had no intention of producing a “Bible.” He was instead organizing his private reflection, seeking to sort the good in religion from the bad within a society that, to a significant degree, regarded the Bible as the revealed Word of God. Jefferson’s reverence for Truth precluded the classic Christian formulation of Truth as revelation. But it would be a mistake simply to characterize Jefferson’s resistance as a preference for reason over revelation. To call a moral code “sublime” is to invoke its affect on a person, and Jefferson’s revision of “Philosophy of Jesus” to “Life and Morals” suggests, if not the supernatural, then an aspect of humanity that is beyond the rational. Jefferson’s Enlightenment involved the heart as well as the mind and, arguably, a version – albeit private – of a soul. Jefferson did not appoint himself judge, jury, and executioner over the popular piety of others. Rather, he tried to streamline his own biblical reading to ensure he could encounter the “diamonds” without obstruction. Enlightenment religion is not as uniform or simple as we tend to think.

The author gratefully acknowledges the work of Margaret M. Mitchell and her 2023 Richard Lectures at the University of Virginia. All errors (and characterizations of the Enlightenment) are his own.

Featured image from public domain