Emptying the Arsenals of Memory

The gap between contemporary and ancient conceptions of memory lie at the heart of the challenge in understanding Israeli and Jewish perspectives on October 7 and its aftermath.

On a recent episode of the New York Times’ “Daily” podcast, David K. Shipler said that both Israelis and Palestinians were “imprisoned by history.” Shipler, who served as the Times’ Bureau Chief in Jerusalem from 1970 to 1984, went on to explain that “two clashing narratives, not overlapping at all,” had nonetheless emerged from two peoples with intertwined histories. These narratives would, especially in times of heightened conflict, cause Palestinians and Israelis to rush to their respective “arsenals of memory” to seize upon narratives “chiseled in stone” in order to claim the moral, political, and public relations high ground.

Shipler, the author of the Pulitzer prize-winning Arab and Jew: Wounded Spirits in a Promised Land, noted the cross-fertilization of history and myth that has long been fundamental to Jewish memory. As the historian Y.H. Yerushalmi famously observed, the rabbis saw the Torah as the blueprint for the whole of history; it was Judaism’s memory forms—its templates for how to remember different sorts of events—which were honed through millennia of ritual, recital, and textual interpretation, that uncovered history’s deeper meaning.

Judaism is not unique in this regard, although its memory forms are rooted in its own singular texts, traditions, and history. The canonized and thus unchanging textual basis of Jewish culture has served as a framework for the dialectical experience of thousands of years of power and powerlessness, exile and return. This framework has held in place a densely woven tapestry of mytho-historical narrative, in which the pull of one thread can rend or reshape the entire fabric. Biblical and rabbinic narratives have become embedded in the archives, the songs, the prayers, the experiences, and thus in the collective consciousness of Jews the world over, and in times of crisis they provide perspective, solace, and inspiration toward recovery and renewal.

Jewish responses to the assault waged by Hamas on October 7 and the war of subsequent weeks have shown that memory is an invisible battlefield in this latest confrontation. Israeli and Diaspora Jews alike have again turned to their texts, their traditions, their history, and their individual memories to contextualize the recent trauma. The Hamas attack has repeatedly been referred to as a pogrom, summoning images of the rape and slaughter visited upon Jewish communities of Russia and Eastern Europe in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The fact that October 7 was the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust has been cited as a reminder that although the near extinction of European Judaism is receding into history, murderous anti-Judaism continues to be a fact of life.

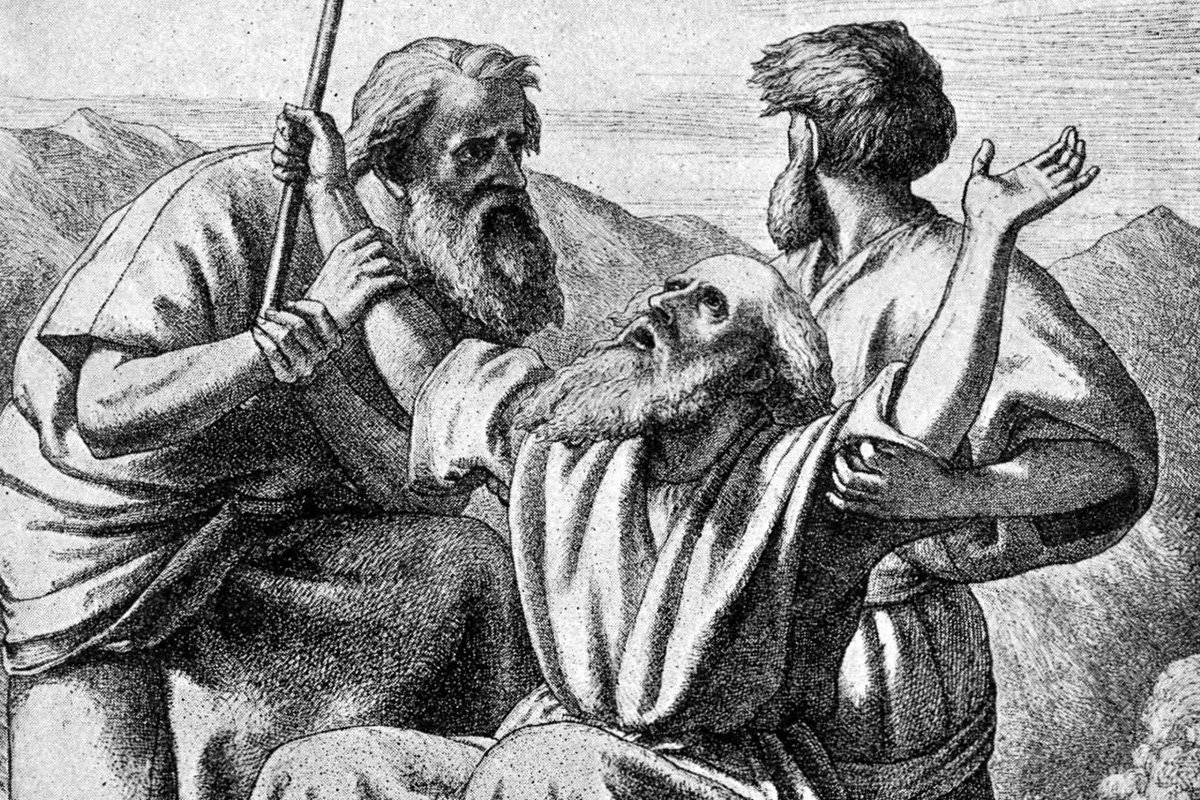

Biblical texts and tropes have been brought forward to summon Israeli battle-readiness. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has compared Hamas to Israel’s ancient enemy Amalek (Ex. 17:8-16; Deut. 25:17-19; 1 Sam. 15), with whom Moses says Israel will be at war “throughout the ages.” Among some ultra-nationalist Israelis, the threat of a wider war has also summoned fevered speculation on the imminence of the Apocalypse.

As Western media are covering eruptions of antisemitic violence and rhetoric at home, Israelis are rejoicing in the freeing of captives, a blessing for which God is thanked in Judaism’s daily liturgy. Israeli media are continuing to report the harrowing stories of the missing and the dead, pieced together from survivor accounts and frantic text messages from the moments before contact was lost. They are also lionizing civilians and soldiers who defended their communities against terrorism. These narratives are rapidly becoming hallowed artifacts in the mnemonic repository of the attack itself. Social media, meanwhile, has served mostly to heighten the tensions and exacerbate the divisions within Western societies by foregrounding sensationalist images of destruction and human suffering with little (and sometimes entirely false) context.

The gap between contemporary and ancient conceptions of memory lie at the heart of the challenge in understanding Israeli and Jewish perspectives on October 7 and its aftermath. In the West, as the literary scholar and medievalist Mary Carruthers noted, the Enlightenment developed a concept of memory that was mechanistic: a retention, reiteration, and duplication of data. However, memory from antiquity through the Middle Ages encompassed a vast array of ideas, experiences, and sensations. As Mira Balberg notes in a recent work, for the rabbis of post-Second Temple Israel, “Memory was inextricably bound with imagination, with emotion, with predilections and inclinations, with dreams and fears . . . One’s religious and communal identity relies not only on memory of the narrated past, but also on memory of the imagined future.” Jewish memory in the postmodern world is often an admixture of these two memory forms: it places the events of Jewish history into the age-old framework of Judaism’s origins. History repeats itself within the confines of this mytho-historical framework.

This framework encourages the detection of primeval patterns repeating themselves throughout history – ancient forms eternally evident in new contexts. In certain ways, this endows Judaism with endurance and resilience. In others, it can limit the ability to accept innovative approaches to intractable challenges. The danger then, as Shipler observed, is that memory becomes not a storehouse of solutions but an arsenal, in which each memory is a form of ammunition to be used against the Other.

Above all, Jewish memory is rooted to the land—but in this, too, Judaism is not unique. On the Daily podcast, Shipler remembered that during a visit to the Jabaliya refugee camp in the Gaza Strip some four decades earlier, he had been introduced to a Palestinian boy of eleven or twelve. He asked the boy where he was from, and the boy replied that he was from Barbarit.

Shipler told the boy he had never heard of the town. Shipler was then told that the boy’s grandparents had fled Barbarit when the village was destroyed by Israeli military brigades in 1948. Although Barbarit had not existed for decades, the boy still knew it as his home.

Featured image: Illustration of Moses holding up his staff during the battle with the Amalekites (from public domain)