All Israel is Bound Together

Conversion and accessibility in the digital age

There is an issue with our connection. Eventually, video and sound align; a woman in her mid-30s pops up on my laptop, calling in from rural Argentina. She explains that she has felt an attraction toward Judaism for most of her adult life, after learning about our community in college. This past fall, she tuned in to my synagogue’s High Holiday services, broadcast via Livestream and made broadly accessible due to the pandemic. She was excited to learn that we had a class for individuals interested in conversion, also moved online while we are unable to gather in person. If we are willing to take her, she would like to sign up.

For most of Jewish history, synagogues have been built and sustained by the local community. The success or failure of a particular institution relied on the continued presence of Jews. Demographic shifts saw the flourishing of the suburban synagogue in the mid-20th century and the struggle to maintain these communities in the 21st as young Jews returned to urban centers. The simple fact is that our ritual lives require other people, not only through religious prescriptions like the minyan—a quorum of ten adults needed to say certain prayers—but also from the emotional and spiritual need of sharing sacred space with others. Judaism asks that we show up for one another; our hearts and souls demand it.

It was this need that required a creative reimagining of what community could look like when the pandemic forced us apart. Synagogues expanded their capacity to stream services. Classes were moved to Zoom. Congregants signed up to call one another and check in. It is important to recognize the loss that accompanied this shift online, as the heartbreak of illness and death was compounded by the necessary distance between us. The screen is an obstacle to the innumerable ways we engage each other without words, whether it is a welcoming smile to someone who just arrived at services or the way a hug can calm and comfort.

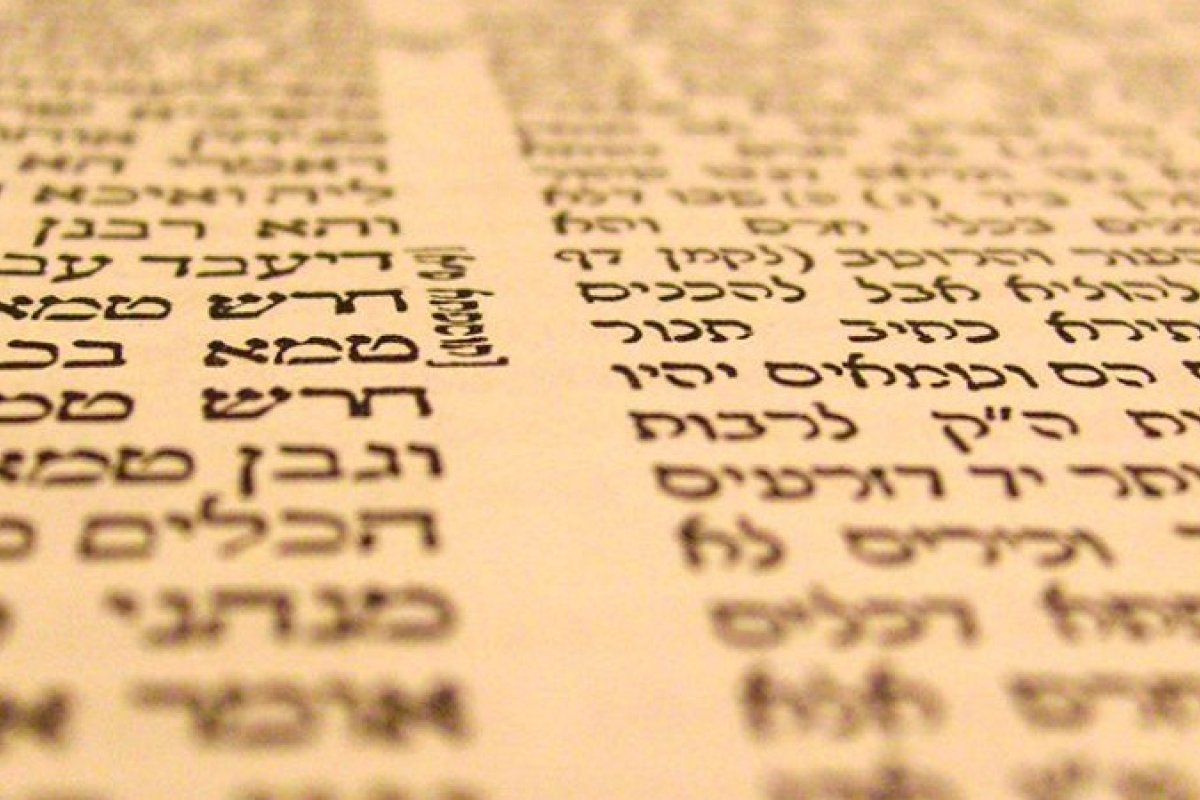

Yet we also found that our communities had expanded in unexpected ways, both heart-warming and powerful. A Jew living in small-town Wyoming attended their first Passover seder in ten years via Facebook. Another tuned in to Shabbat services from their hospital bed. Relatives from around the world celebrated teenagers becoming b’nai mitzvah, their smiling faces filling the large screen we had set up in our sanctuary. New meaning was brought to the rabbinic teaching: Kol Yisrael aravim zeh ba-zeh – all of Israel, whether near or far, is bound with one another (Talmud Bavli Shevuot 39a).

We also began to receive inquiries from people in other states and countries interested in exploring Judaism. For the past few years, I have helped run our conversion program: small cohorts of students who spend several hours every Tuesday learning about Jewish history, culture, belief, and practice. Generally, our students live in Manhattan (joined by the occasional Brooklynite). When the pandemic started, we moved the class online, envisioning that by the time we began the next cohort we would be back to meeting in person. But when it became clear that social distancing measures would extend into the months ahead, a new possibility arose: our students could include some of those people who had contacted us from distant locations. The first to sign up for our class was a person who would have to drive five hours to reach their nearest synagogue. The next was an individual living in Colombia, whose local Jewish community did not accept LGBTQ+ people. Another was a woman in Puerto Rico, who appreciated that our synagogue had female clergy and leadership.

What brought these people together was the feeling that Judaism is their spiritual home, an attraction of both clear vision and inarticulable emotion. In the words of one of my students, they are here because it just makes sense. When Moses addresses his people at the foot of Mount Sinai, he explains that the covenant between God and Israelite is given to both “those standing here with us this day before the Lord our God and those who are not here with us this day” (Deut. 29:13-14). Who are these absent Israelites, the rabbis ask? They answer: all future generations of Jews, including those who join our community by choice (Talmud Bavli Shevuot 39a). In the rabbinic imagination, the convert is not someone who finds us by chance, but one who seeks out Judaism because this is where they belong. For those of us who work with conversion students, the message is clear: this is holy work.

There is no doubt that we should welcome all those genuinely seeking a place in our community. The question that remains is what happens to these individuals once we have returned to our brick-and-mortar buildings. While it is clear that we have entered a new era of online access to religious community, I fear that the long-delayed joy of being back together will narrow our focus to the people standing in front of us. We must be careful to broaden our vision, asking ourselves the same question posed by the rabbis centuries ago: who are the people not here with us this day? It is hard to be a Jew alone, and this is especially true for converts, who often lack the same support networks as those born into our people. Their Judaism is one of particular conviction and hard work, whether they live in urban America or rural Argentina. We must continue to meet them in kind, in-person and online.

In the end, it is not only for the sake of converts that we must continue to think about how our communities can remain accessible. The ability to simply “click” into services, classes, and lifecycle events has brought numerous people to our synagogues who might otherwise be absent. Whether we are born into this community or come to it later in life, the call of Mount Sinai is our shared inheritance; yet each of us must choose whether we will take our place at the foot of the mountain. When we begin to gather again, we must ensure that the various pathways into our community remain open – for we are bound together, wherever we may be found.

Photo: Chajm Guski, via Wikimedia Commons

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.