“. . . you’re doing it right now”: Aaron Bushnell and Legal Pluralism

What if we understand Aaron Bushnell’s action as opening onto a different legal order—and collectivity—one to which we all also belong?

On February 25, 2024, Aaron Bushnell set fire to himself outside the Israeli embassy in Washington DC. A member of the US Air Force stationed near DC, Bushnell transmitted a live videorecording of himself in front of the embassy, announcing that his intention was to perform an extreme act of protest against genocide. He poured gasoline over his head and set himself afire, calling out “Free Palestine” as he burned. Law enforcement officers are seen rushing to the scene, one holding a gun on Bushnell as he burns, the others deploying fire extinguishers.

In advance of his burning, Bushnell posted this message on his Facebook page:

"Many of us like to ask ourselves, “What would I do if I was alive during slavery? Or the Jim Crow South? Or apartheid? What would I do if my country was committing genocide?”

The answer is, you’re doing it. Right now."

We were all doing what we were doing during these times. Aaron Bushnell did something else. How might we begin to understand what he was doing?

There is much that could be said and needs to be said about what is being called a self-immolation. Even so, there has been remarkably little news coverage of his act. Perhaps because his act appears illegible or terrifying to many of us, or because we do not know what to compare it to. We would rather not think about it. In this short reflection, I will think through this act not simply as that of a single individual but as a collective act, one that invokes an alternative legal order and challenges the dominant legal order.

For the most part, press accounts which have reported on the event have seen what Bushnell did as the choice of a single person. They have rehearsed what has become a familiar repertoire. For those wishing to contain and silence him, he was either a terrorist or mentally ill. Hence the gun and the fire extinguishers. For those more sympathetic to his political views, he is described as an idealist—a self-sacrificing hero. The individual of conscience over against the state. Still another narrative has emerged linking him to a religious community in which he was raised, one described in the press as cult-like and controlling. How this raising explains his act is unclear to those reporting on it, except that such religious discipline seems to be understood as likely to make you unbalanced. The secret service called it a mental health crisis, but they also held a gun on him. The state seemed confused as to whether they wanted to save him or kill him.

Aaron Bushnell called his act “an extreme act of protest.” It was not simply an act of individual conscience. It made a claim and demanded a response. But to whom was his act addressed? The last line of Bushnell’s Facebook post is addressed to us. “You are doing it right now.” It constitutes us as in community with him. It invites us into a relationship—a community alternative to the activities of the state and its asserted rights to defend its property and its borders. We are constituted as an unstately community—one that refuses the secularism of the modern state and is thus necessarily both legal and religious, in a broad and robust sense.1

There has been much interesting, moving, and important writing about self-immolation, including in the context of the hundreds of Tibetan Buddhists who have set fire to themselves in recent decades. Scholars have carefully analyzedBuddhist teachings and histories as well as the contemporary history of the Tibetan community under the Chinese regime. Others have written about the Vietnam era burnings, and more recently the burning of Mohamed Bouazizi, the act that instigated the Tunisian Revolution of 2011 and the “Arab Spring.” How do these previous instances of self-immolation help us to understand Aaron Bushnell’s act and the claims it makes on us?

I believe that Bushnell’s act makes a legal claim on us, not just a claim of conscience. In other words, Bushnell’s actions are authorized by an alternative normative order, a law beyond that of the modern state and of the international order of nation states. One way in which that can be seen is in how Bushnell’s burning shifted the burden of proof, in a legal sense. That is, it placed responsibility for Bushnell’s own death at the hands of the US and Israeli governments, in a demonstration of what Mitra Sharafi calls the work of “legal pluralism.”

In an article on the forensic use of blood-testing in colonial India, Sharafi has shown that incidents of what she calls “punitive self-harm” should be understood as examples of an encounter between legal cultures, one in which South Asian actors worked to enlist the British colonial legal authorities in service of a non-colonial normative order, rather than as the British authorities viewed them, as examples of native mendaciousness and corruption. She explains that “Punitive self-harm had a long and varied history in south Asia, including Gandhian modes of non-violent resistance (like the hunger strike), political protest suicides, and even some cases of sati or ritual widow immolation. At its core was the idea that a person would hurt him- or herself to protest a wrong done by another.” She continues, “While colonial criminal law... operated upon the basic assumption of individual responsibility and punishment, ... [t]hese cases reflected a model of collective identity, responsibility, causation, and punishment that was so foreign to [the British official’s] own cultural logic that he failed to understand what he was observing.”

As in colonial India, protest in Washington brings with it an entire religio-legal culture, a law, that is, which is often not understood to be proper law. Paradoxically perhaps, while journalists and lawyers in the US often report on religion as something that has non-negotiable prescriptive rules about what one should do or not do, about abortion or suicide for example, those rules are not regarded as real law with a legal culture underlying them. I argue that protest invokes real law, law founded in religious understandings of the human and of human community, as well as of conceptions of justice and culpability—law that rivals the claims of modern secularist state law.

In a powerful illustration of the failure of modern state law to provide justice and care, David and Jaruwan Engel describe the alternative legal consciousness of accident victims in contemporary Northern Thailand. They show how Buddhist and other Thai customary legal norms and practices often substitute for the modern legal institutions of the Thai state, ones that accord with the victims’ own collective religio-legal understanding of human motivation, causation, and justice. As with Sharafi, the Engels show us a mixed legal order in which victims robustly mobilize alternative legalities to achieve compensation and justice, challenging the assumptions and adequacy of modern secular state law.

The video of Aaron Bushnell’s burning hauntingly calls to mind the burning scene from Theodore Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. In a forthcoming book I argue that she too acted out of an alternative legality, a vernacular and collective political theology. Joan of Arc died almost six hundred years ago, on May 8, 1429. While often celebrated as a lone act of sacrifice, she said before she went to the stake that she wished to be faithful to the collectivist politics to which her voices called her.

In each of these cases we see the persistence of collective religio-legal orders that have successfully challenged the adequacy of modern state law and made visible the persistence of legal pluralism. These examples teach us that modern state law and rule of law ideology do not in fact enjoy, and do not deserve, the monopoly they claim for themselves. What if we understand Aaron Bushnell’s action and address to us as opening onto a different legal order—and collectivity—one to which we all also belong? Not the abstract universalism of international law but a law closer to the ground and to an embodied human experience? The legibility of that gesture would depend on accepting a more permeable state, one that does not monopolize all law and all violence but one that is appropriately vulnerable to critique from unstately legalities.

Ralph Litzinger, in a short essay on Tibetan self-immolations, comments: “It is using fire to steal from the state its foundational relationship to violence. It is denying the state, if only for that singular moment when the body ignites in flame, its sovereign claim to determine how individuals, in this most precarious of times, will be cared for, how they will live, and how they will die.” The confused response by the secret service agents responding to Bushnell’s burning, along with many other examples we could name, is an indictment of the state’s sovereign claim to sufficiency in the face of the counter-sovereignty of death.

Notes:

1 Critique of the modern state is a large, diverse, and complex political and intellectual project. I am sympathetic to those for whom the long history of the modern state’s formation has resulted in a silencing of alternative religio-legal forms of sociality and care, alternatives that have nevertheless persisted, even when only occasionally acknowledged. See, e.g., Tracy E. Hucks and Dianne M. Stewart, Obeah, Orisha, and Religious Identity in Trinidad (Duke 2022) and J. Kameron Carter, The Anarchy of Black Religion: A Mystic Song (Duke 2023), as well as the work of Carlo Ginzburg on the peasant politics of early modern Europe.

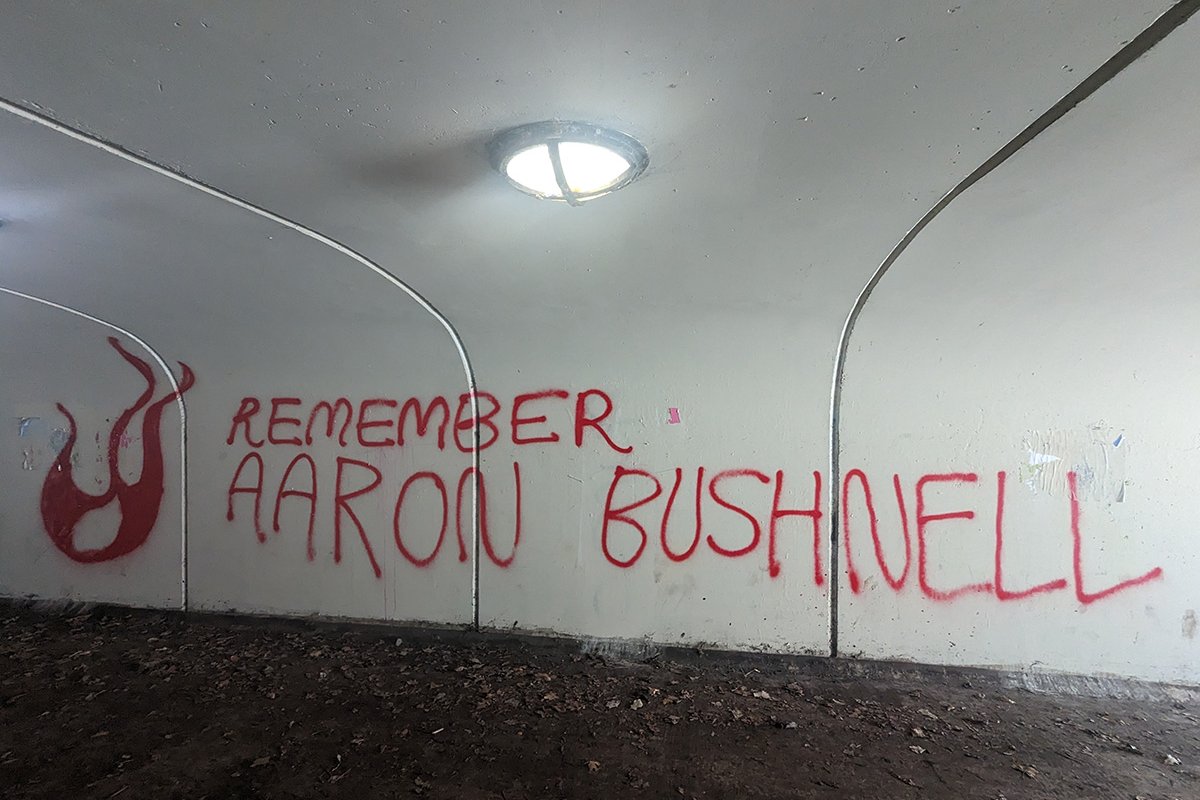

Featured image: Graffiti on the walls of the 55th Street underpass in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood.