What Makes a Conflict "Religious"?

Sometimes our categories conceal more than they reveal

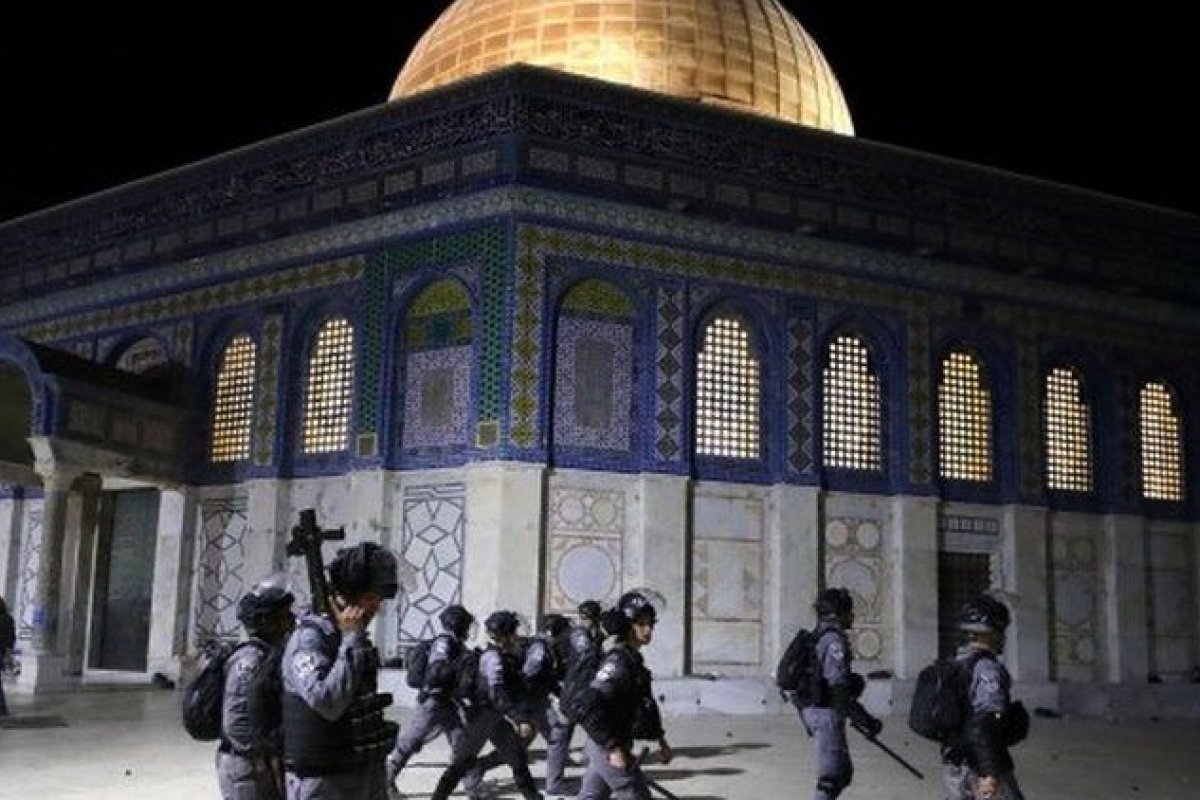

A month ago, violence broke out at al-Aqsa Mosque in East Jerusalem. As the BBC reported, Israeli police fired rubber bullets and stun grenades as Palestinians threw stones and bottles. The timing and location of these events is significant. The violence occurred right after around 90,000 Palestinian Muslims gathered at the mosque to pray and celebrate the last Friday of the holy month of Ramadan, and Al-Aqsa is one of the three holiest mosques in the Islamic tradition. It stands on the Temple Mount, which is sacred to Jews.

There is no denying that this tragedy, and the broader conflict it is a part of, has strong religious dimensions. However one defines “religion,” religion plays a role in the motivations and justifications of many of the actions taken by leaders and protesters. But framing the current situation in Palestine as a religious conflict, and the violence that occurs as religious violence, is potentially misleading.

Though some have argued that the term “conflict” fails to do justice to what is happening on the ground, I will focus more on what is revealed and concealed when we label violence as “religious.”

As William Cavanaugh argues in The Myth of Religious Violence, “The distinction between secular and religious violence is unhelpful, misleading, and mystifying, and it should be avoided altogether.” Cavanaugh argues that the historical narrative adopted by many in the West, in which religious adherence makes people prone to violence while secular, liberal nation-states offer a more peaceable and reasonable alternative, is false. Religious groups certainly can be violent, but the ideologies of the secular nation-state serve to agitate and legitimate violence just as readily as do those labeled “religious.”

Moreover, the constellation of forces motivating “religious” and “secular” violence often share considerable overlap. Religion is almost always but one factor among many, and it is difficult to isolate from other factors. Even when we examine the so-called “Wars of Religion” in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe, Cavanaugh argues, religious conviction is rarely the decisive factor that makes conflicts violent or intractable. In some cases, even to call religion a “factor” would be misleading—religious rhetoric is used to rationalize and sanctify violent actions that are simultaneously driven by colonial, revolutionary, expansionist, or economic goals. While we need to recognize the religious significance of contested sites and the role religions play in the formation of “us versus them” antagonisms, characterizing conflicts as “religious” foregrounds religion while deemphasizing and obscuring other reasons why people use violence.

One effect of this characterization is that acts of violence deemed religious are sometimes put into a separate category and not given critical, moral evaluation. In the popular imagination, religion functions as what Richard Rorty famously called a “conversation stopper.” When we identify a particular action as religiously motivated, we are, in effect, saying that it cannot be accounted for in terms of motivations that could potentially be shared by people outside that particular religious group. In our everyday discourse, we tend to treat religion as a motivator sui generis—a source of motivation independent from human concerns about security, well-being, national identity, family, land, and property.

One reason for this is the prevalence of “religion-of-the-gaps” explanations of others’ behaviors. When we cannot understand (or choose not to understand) others’ motivations as emerging from concerns like our own, we tend to rely on simplistic explanations that attribute their actions to religion. In so doing, we imagine their religion as an autonomous and irrational source of convictions, which are detached from and often at odds with more practical, reasonable approaches to understanding the world and meeting one’s needs. This also applies, though perhaps not to the same degree, when we pin the label 'religious' to our own commitments. For example, one commitment I have is that I do not swear oaths, because Jesus says not to do so in the Sermon on the Mount. If someone asked why I refuse to place my hand on the Bible in court, I would be able to offer no explanation besides citing that same Bible and saying, 'It's against my religion.' By contrast, another commitment I have is opposition to racism. This is no less rooted in my faith, in particular the belief that all people are made in the image of God. But I would rarely call this commitment 'religious' since it appears readily intelligible to others without invoking religious texts or traditions. In either case, since we tend to characterize behaviors as religious only when we cannot account for them in other terms, religion becomes identified with the unintelligible, with what is not accessible to rational scrutiny and moral deliberation.

Cavanaugh warns that identifying some violence as religious (and therefore non-rational) serves to legitimate forms of violence that are deemed secular, even if this violence is comparatively more unjust or repressive. This is a dangerous illusion, since, as Cavanaugh says, “There is no reason to suppose that so-called secular ideologies such as nationalism, patriotism, capitalism, Marxism, and liberalism are any less prone to be absolutist, divisive, and irrational than belief in, for example, the biblical God.” The myth of religious violence not only diverts attention away from secular violence but is also used to justify it.

Cavanaugh’s point is fascinating (and contested), but I argue there is another danger to describing some conflicts as religious. Labeling a conflict religious can make us less likely to critically examine the actions of those involved, discerning whether they are defensible or indefensible. It makes it seem as if our normal categories and judgments of political ethics do not apply. It can also give the impression that the roots of the conflict go back millennia, and that the conflict is a natural outcome of religious difference rather than the result of political decisions. Alain Epp Weaver writes, “Rather than being ancient, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a thoroughly modern phenomenon, stemming from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.” He continues, “talk of age-old enmity presents the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as uniquely intractable, with efforts to resolve or transform it deemed hopeless from the start.” Framing the situation in Palestine and Israel as a “religious conflict,” I argue, has a similar effect on Americans and other onlookers. The popular American assumption that the Middle East is an incomprehensible hornet’s nest is sustained, in part, by thin descriptions of particular religions or religion in general.

A clear understanding of the roles that differing religious ideologies play in socio-political conflicts is incredibly valuable. But what comes to mind when we hear the words “religious conflict” or “religious violence” is liable to be a distorted picture that does not match the realities faced by Israelis and Palestinians.

Photo: Israeli Police last month at the Dome of the Rock, on the Temple Mount near Al-Aqsa Mosque (Ammar Awad | Reuters)

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.