We Need Fewer Heroes

Exploring the tension between our praise of everyday heroes and the social instability that necessitates them

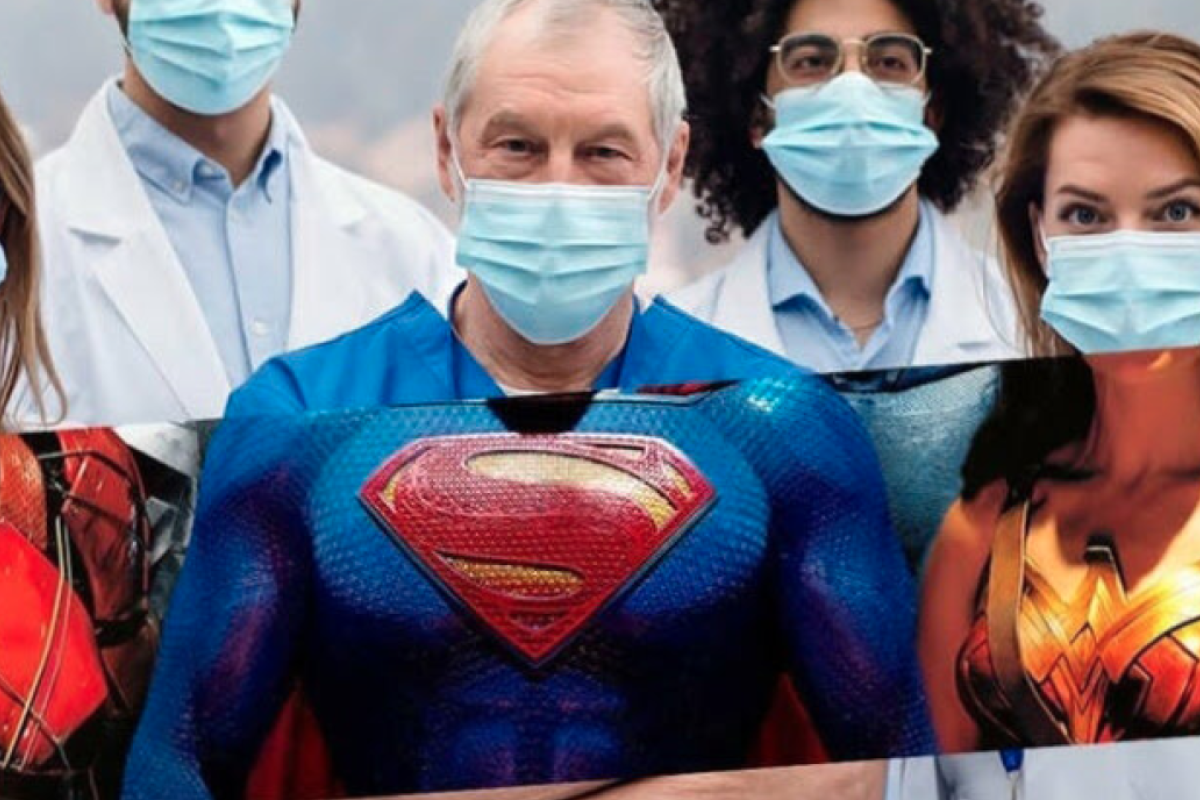

Since the beginning of the quarantine, two sentiments about frontline health workers have been expressed from many corners. The first is an outpouring of gratitude and respect for nurses, doctors, volunteers, and essential workers who have stepped up to address the dire needs brought on by COVID-19 and the responses. Hundreds of commercials, TV personalities, murals, social media posts, and “7:00 pm celebrations” have honored these heroes who continue to put themselves at greater risk of exposure in order to help others and keep the country functioning.

The second sentiment is one of frustration. In response to the Blue Angels flying over several major cities, an especially out-of-touch tribute to healthcare workers, Solomon Jones writes, “I am stunned that while health-care workers don’t have the personal protective equipment (PPE) they need to safely work in highly contagious environments, President Trump would send warplanes rather than medical supplies.”

Earlier this year, Jillian Primiano, a nurse in Brooklyn, wrote a protest sign saying “Please don’t call me a hero. I am being martyred against my will. Defense Production Act now!” The Defense Production Act (DPA) is a law passed during the Korean War (1950) which allows the President to require certain businesses to produce items deemed necessary for the national defense. President Trump invoked it in April, but many critics deemed his actions too little and too late to provide adequate protective equipment for healthcare providers.

In an interview, Primiano added, “I don't want to be called a hero, but I also don't want to let people die. Calling me a hero empowers you to tell me that's enough because that's the highest compliment that you can give me. I don't need a compliment; I need safe staffing. I need to have a number of patients that I can manage and keep well. I need the right equipment that works.” Many other doctors and nurses have expressed the same frustration with the disparity between the abundant outpouring of praise and the lack of institutional support to actually meet the needs these “heroes” have. When the nation’s representatives aren’t doing all they can to provide healthcare providers with life-saving N95 masks, the applause can start to sound hollow.

There is also a deeper critique here: if the nation’s leaders had taken more decisive action, the United States would not be leading the world in COVID-19 cases and the crisis would not call for as much self-sacrificial action from healthcare providers. The federal government’s culpable lack of preparation exacerbated the crisis, increasing the demands on healthcare providers’ bodies and minds.

Put plainly, if the nation has proper infrastructure in place, there will be less of a need for people to put themselves in harm’s way for others. The more we’re able to anticipate, prevent, control, and provide during crises, the less need there is for heroes. Strange as it sounds, a world with fewer heroes would be a good thing.

As humans, we love to celebrate heroes. They give us role models to look up to, the inspiration we need to overcome setbacks and obstacles, and reassurance that the world is not all bad. Stories about heroes—real and fictional, known and unheralded—are told and retold in movies, books, and news stories. Every religious tradition holds up heroes who courageously faced challenges and sacrificed for others.

Heroes should be lionized and emulated, but we must not let their heroism distract us from the need to make the boring, preventative, structural decisions that future generations will take for granted. This is the banality of good—the fact that if a lot of people make small, unremarkable actions to make things better, these can result in a healthier, more equitable world. We should be grateful for the actions of a few heroes risking their lives to save others, but we honor those heroes best when we work to ensure that others won’t have to take on the same burden.

Fred Rogers memorably said that in scary times, we should “look for the helpers.” This is good advice, but incomplete. We should also look for the structural factors that contributed to the critical situation or could have meliorated it. Sometimes looking for the helpers can distract us from the need to establish, fund, and maintain the programs that—though they are much less dramatic than acts of bravery—contribute to the well-being of the population.

This tendency to focus on the dramatic runs deep in the American psyche. As Sigrid Ellis wrote, “Americans are really good at acute compassion, but pretty bad at chronic empathy. We, without question, haul strangers out of a raging flood, give blood, give food, give shelter. But we are lousy at legislating safe, sustainable communities, at eldercare, at accessible streets and buildings. It is the long-term work that makes disasters less damaging. But we don't want to give to the needy, we want to save the endangered. We don't like being care workers, we want to be heroes.”

There is some truth to the idea that robust social programs, if successful, might make people more complacent and less likely to perform virtuous acts of generosity and self-sacrifice. But it’s unreasonable to imagine that any society could ever reduce the opportunities for acute compassion to the point where its character-forging benefits are substantially lost. As Reinhold Niebuhr reminds us, there never will be a utopia. We will always have crises and always need heroes. As the current pandemic reveals, no amount of infrastructure and legislation could remove the need for courageous people to step up. But, as Niebuhr also reminds us, the diligent study of history reveals more or less predictable patterns. Through collective action, we can put programs in place to mitigate the damage caused by viruses, natural disasters, and human selfishness.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.