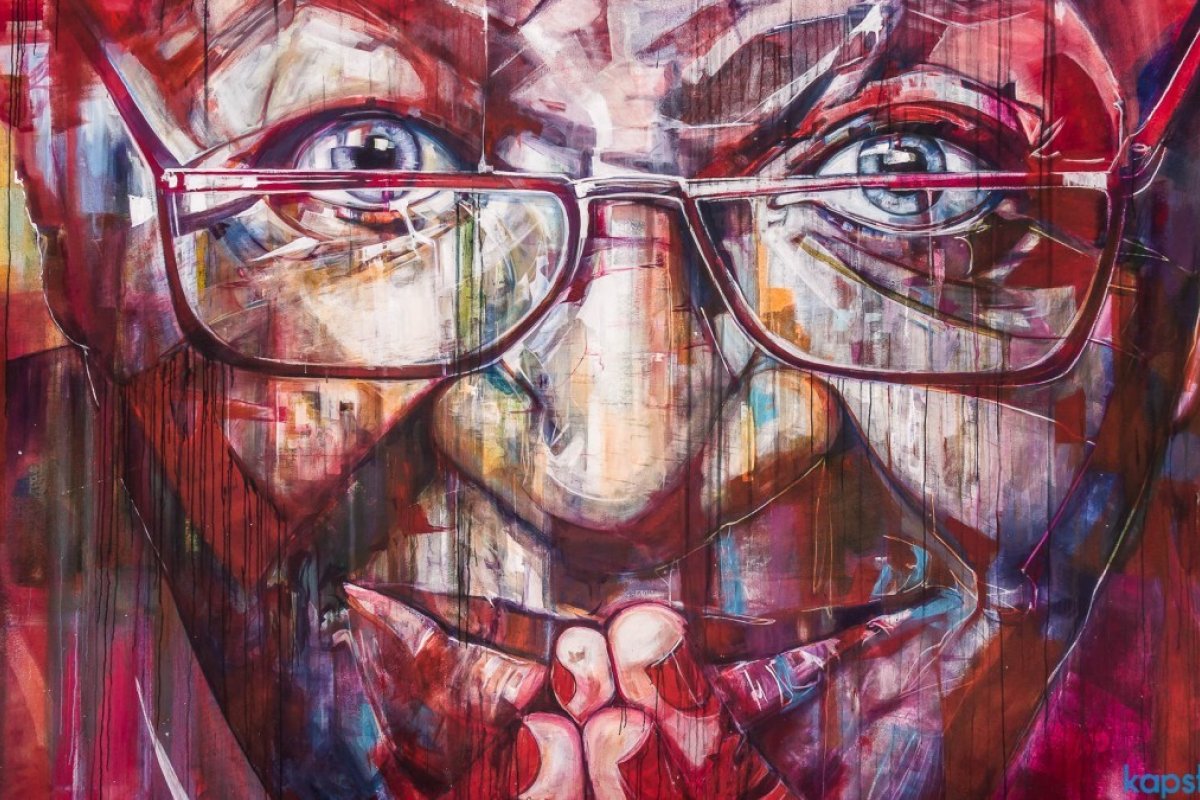

The Revolutionary Joy of Desmond Tutu

There is a danger in softening Tutu’s legacy, but we make the same mistake in the opposite direction if we forget his contagious, all-embracing joy.

When Archbishop Desmond Tutu passed away on December 26, my Facebook news feed was filled with homages to two different men.

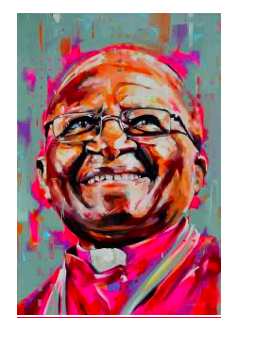

On the one hand, there were pictures of Tutu the jovial, laughing sage, accompanied with quotations about hope and reconciliation. This Tutu joked around and jumped around, bringing a Mister-Rogers-like warmth to the interviews he gave and the children’s books he wrote. This Tutu hugged a Muppet on Sesame Street and danced with the Dalai Lama, with whom he co-authored a book about joy.

On the other hand, there were quotations from the radical firebrand Desmond Tutu. This Tutu was the “most hated” man among white South Africans during his 1980s protest campaign against apartheid. This Tutu prophetically challenged political leaders around the world, called for sanctions against his own government, and insisted that no one can be neutral in times of oppression.

How do we reconcile these two sides of Desmond Tutu? The simple but wrong answer would be to say that Tutu started out as a controversial crusader for justice but, after a long and successful career, retired into the life of a sagacious, smiling Nobel Peace Prize winner. What that story gets wrong is that these two sides of Tutu’s personality coexisted for his entire career. Late in life, Tutu was not just a humorous and popular graduation speaker but an outspoken critic of war and ongoing political repression.

These two sides were both present early on, as well. As journalist Lin Menge wrote of Tutu in 1981, “One minute he seemed to be whipping up a riot. The next minute he has stopped it, cold. And then he has his audience laughing... One minute whites were being swept along, submerged, in a black political tirade; the next minute, they were being set down, safe and sound, on the sunny banks of racial amity.”

This dialectical display was not only a feature of Tutu’s oratory; it reflects the very heart of his theological and political vision.

For Tutu, human beings are created to live in relationships of mutuality and interdependence. Unjust policies that keep people from flourishing in community with one another are thus violations of the divinely-given order. These injustices can last for generations and cause unspeakable pain, but Tutu insists that they will not triumph in the end. He writes, “This is a moral universe, which means that despite all the evidence that seems to be to the contrary, there is no way that evil and injustice and oppression and lies can have the last word.” Because of this hope, people are capable of working to end the social structures that stand opposed to human value and harmony. For Tutu, hope is not naïve optimism; it is only people who have hope who can truly recognize that suffering and violence are not part of how the world ought to be. Only those who have hope can resist the temptation to numb themselves to their own suffering and the suffering of others.

For Tutu, human beings are created to live in relationships of mutuality and interdependence. Unjust policies that keep people from flourishing in community with one another are thus violations of the divinely-given order. These injustices can last for generations and cause unspeakable pain, but Tutu insists that they will not triumph in the end. He writes, “This is a moral universe, which means that despite all the evidence that seems to be to the contrary, there is no way that evil and injustice and oppression and lies can have the last word.” Because of this hope, people are capable of working to end the social structures that stand opposed to human value and harmony. For Tutu, hope is not naïve optimism; it is only people who have hope who can truly recognize that suffering and violence are not part of how the world ought to be. Only those who have hope can resist the temptation to numb themselves to their own suffering and the suffering of others.

Tutu saw this numbness in the supporters of apartheid, and both his laughter and his protests were efforts to call his opponents back to their own humanity. The brilliance of Tutu is that even in his most bracing condemnations of racist policies, he was always inviting others, including his enemies, into a way of living characterized by mutual enjoyment, compassion, and celebration of difference and diversity.

As Tutu writes, “In a real sense we might add that even the supporters of apartheid were victims of the vicious system which they implemented and which they supported so enthusiastically. This is not an example for the morally earnest of ethical indifferentism. No, it flows from our fundamental concept of ubuntu. Our humanity was intertwined. The humanity of the perpetrator of apartheid’s atrocities was caught up and bound up in that of his victim whether he liked it or not. In the process of dehumanizing another, in inflicting untold harm and suffering, inexorably the perpetrator was being dehumanized as well.” The two dimensions of Tutu’s character are ultimately two sides of the same coin: a revolutionary joy that subverts the prejudices and injustices which prevent us from experiencing our full humanity.

There is a danger in softening Tutu’s legacy by focusing only on his whimsical side. Cornel West has warned against the “Santa-Clausification” of Martin Luther King Jr. in public discourse, and the same thing can happen if we turn Tutu into a simple feel-good story or reduce his message to one of hope and forgiveness. But we can make the same mistake in the opposite direction if we forget that the contagious, all-embracing joy Tutu exhibited was also a crucial part of his prophetic witness.