Religious Art Discovered Alive!

No “-scope,” either “micro-“ or “tele-,” was needed last week for us to sight an article written “as if” for Sightings, so bold was its headline, so appropriate to be appropriated by this column on “religion in public life,” given our focus on art and religion in that sector

No “-scope,” either “micro-“ or “tele-,” was needed last week for us to sight an article written “as if” for Sightings, so bold was its headline, so appropriate to be appropriated by this column on “religion in public life,” given our focus on art and religion in that sector. It reads: “Reports of the Death of Religious Art Have Been Greatly Exaggerated.” Author S. Brent Plate (Hamilton College) ranged widely as he offered and commented on examples illustrating his thesis. This week, dear readers, do not overlook his piece in our “Resources” section. It is impossible for us to give even one-line mentions of the many artists on whom he comments, or to do justice to his perceptions.

No “-scope,” either “micro-“ or “tele-,” was needed last week for us to sight an article written “as if” for Sightings, so bold was its headline, so appropriate to be appropriated by this column on “religion in public life,” given our focus on art and religion in that sector. It reads: “Reports of the Death of Religious Art Have Been Greatly Exaggerated.” Author S. Brent Plate (Hamilton College) ranged widely as he offered and commented on examples illustrating his thesis. This week, dear readers, do not overlook his piece in our “Resources” section. It is impossible for us to give even one-line mentions of the many artists on whom he comments, or to do justice to his perceptions.

To the point: Plate is not interested in art that expresses what he calls “a nebulous personal ‘spirituality,’” or, further, which only “work[s] against religion,” or proselytizes for Thomas Kinkade-type kitsch. He leaves aside those historians and theorists who have filled libraries with writing on pre-modernist art. His concern is with those who choose not to comment on modern “art that sets out to convey spiritual values” because, they believe, it “goes against the grain of the history of modernism” (Jim Elkins’s phrase). Plate refers positively to the work of former fellow Chicagoan Sally Promey, who noted “the lack of attention to religious motifs and themes” in the literature on American art history.

Plate criticizes critics and journalists who “rarely diverge from the secular gaze when it comes to using art and spirit in the same sentence.” He is weary of reviews of exhibitions which “often go out of their way to dismiss, willfully ignore, or downplay the clear religious dimensions.” After millennia in which art could not be “detangled” from religion, he is uneasy about the “dominant myth of modernity (and modernism),” which holds “that we have finally freed ourselves (and our art) from a parasitic dependence on religion and its symbols, rituals, and myths,” and have chosen to live in the world that Max Weber called “disenchanted.” On that front, to revisit Plate’s headline, “Reports of the Death of Religious Art Have Been Greatly Exaggerated.”

Plate’s news, with that modern mythology as backdrop, is that recent publications in this field “indicate a significant shift in religion-art relations.” Citing authors who are aware of this shift (Donald Preziosi, Jonathan A. Anderson, William A. Dyrness, Mark C. Taylor, and a score more), Plate draws, with them, on “a theological perspective,” and jauntily summarizes his findings: “Dig around in art, and we find religion. Dig around in religion, and we find art.”

The authors to whom he refers deal with an “amassing of imagery” and “[t]hemes of creation, memory, embodiment, ritual, mourning, afterlives, and culture difference.” Plate particularly notices Karen Gonzalez Rice’s work, wherein she examines religiously informed art relating “to endurance, the body, and ultimately suffering and potentially healing,” thus shifting away “from what the artists believed, pointing instead toward the practices of art, the bodily-based disciplines, sufferings, and desires.” Plate is ecumenical enough to turn his not-merely-secular-gaze to Islamic and Jewish expressions, where he finds iconic emergences in faith communities long known as “aniconic.”

Readers curious about these subjects would do well to note Plate’s sources, and then do their own discovering. Lest we be carried away by the thrill of reading about these approaches, we should note that Plate is sufficiently culture-bound to announce that, with one exception, these writers are not “advocating an experience with a traditional god, or encouraging pews to be filled again in church and temple. Strictly speaking,” he reminds us, they (and he) are interested in “secular accounts of secular arts,” art that “is not created in the service of religious institutions.” At stake, then, is “a reenchantment of the art world, and, by extension… of the secular world as a whole.” We ask: might not there be someone, somewhere in the world of the billions of seekers who stand in some meaningful relationship to the many extant and often expanding religious—ugh, pardon the word!—“institutions,” creating startlingly fresh art that may yet emerge in times of post-disenchantment?

Resources

- Plate, S. Brent. “Reports of the Death of Religious Art Have Been Greatly Exaggerated.” Los Angeles Review of Books. January 24, 2017.

- Rice, Karen Gonzalez. Long Suffering: American Endurance Art as Prophetic Witness. University of Michigan Press, 2016.

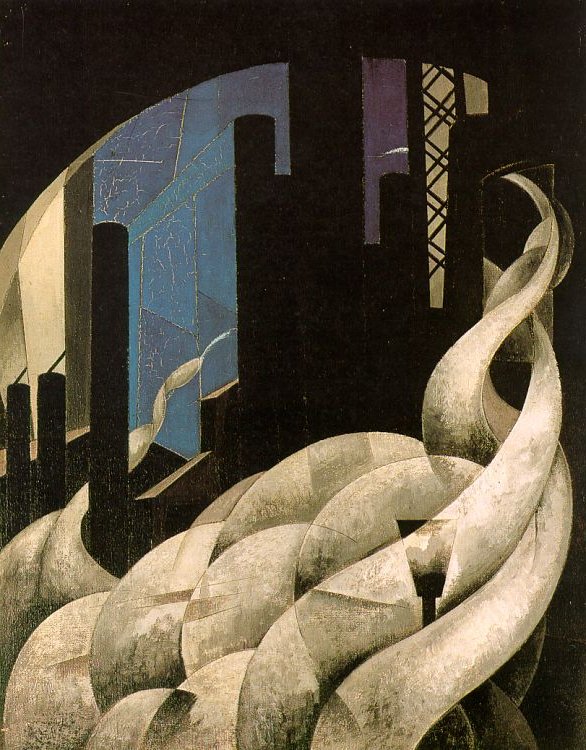

Image: Incense of a New Church (1921), by American modernist painter Charles Demuth

Author, Martin E. Marty, is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. Author, Martin E. Marty, is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco, a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Click here to subscribe to Sightings as a twice-weekly email. You can also follow us on Twitter.