Relief After Misfortune

A centuries-old Islamic literary genre may still offer consolation today

In a recent article surveying the impact of Covid-19 on our lives, Lawrence Wright records stories of both despair and hope. He talks about James L. Miller, an army veteran who took part in the Normandy Beach landing on D-day and later became a postal worker and firefighter. At 96 years of age, he contracted Covid-19 and after suffering for several days, passed away, sequestered from his family. Another story refers to Jim Klobuchar (father of former presidential candidate Amy Klobuchar) who also fell severely ill with the coronavirus at the age of 92. When Amy Klobuchar visited her father at the assisted-living facility where he was living, she assumed that that would be the last time she would see him alive. But Jim Klobuchar, who sang “Happy Days Are Here Again,” to his daughter during their meeting, beat the odds and survived his encounter with the deadly disease. Another survivor was 29-year-old Chris Rogan, who had to be intubated after he contracted Covid, yet found the resolve to keep going, even after one of his legs was amputated, by “conversing with God” (as the article describes it), who assured him that he would make it.

The well-written essay is a powerful reminder that life is full of vicissitudes that often fill human beings with anxiety and despair. We can never be sure of the outcome – we can choose to give in to despair, or we can consciously adopt a more hopeful stance. Many turn to religion and faith in a higher being to find the moral courage and determination to persevere in the midst of uncertainty and tragedy. In a survey conducted by Pew Research Center in spring, 2020, a quarter of adult Americans said their faith had grown during the pandemic.

If we turn our attention to Islam and its sacred text, we find that hope is very much at the center of the message that it imparts to humanity. The Qur’an (39:53) counsels us not to give in to despair when confronted by afflictions. It considers life in this world to be purposeful and ever advancing towards a future that will be just and filled with hope, whether realized in this world or the next. Indeed, the Qur’an (94:6) promises that after hardship comes ease.

This Qur’anic message led the Japanese scholar of Islamic Studies, Toshihiko Izutsu, to describe Islam in one of his publications as a religion of optimism which challenged the characteristic pessimism of pre-Islamic Arabian society.[i] The optimism that Izutsu discerned in Islam’s holiest text did indeed permeate many aspects of Muslim societies, and left its imprint on literature and the arts as well. This optimism carried over into a literary genre that became particularly popular during the medieval period in a broad swath of the Muslim world. In Arabic, this genre is known as al-Faraj ba‘da al-shidda, which can be translated as “Relief or Deliverance after Misfortune,” reflecting the promise contained in Qur’an 94:6. Muslim thinkers and writers of the time sought to provide consolation to their fellow human beings by sagely affirming that occasional misfortunes are a natural part of human life. But they always come to an end, and life becomes good and hopeful again after they pass. Basic human resilience could be called upon to weather these temporary storms that afflict everyone; there was always a safe harbor to be found after life’s inevitable trials and tribulations.

The Faraj ba‘da al-shidda genre was not strictly a religious one, even though its content often had an overtly moral and homiletic purpose. It was more a part of the rich humanistic literature known in Arabic as adab, which means manners and morals, and refers broadly to the humanities. Adab works were composed by gifted litterateurs who culled the collective wisdom of humanity in order to provide not only advice to their readers but also literary entertainment. Such works were very popular with those who belonged to the educated, reading public of the time, composed of princes and other members of the aristocracy, courtiers, professional secretaries, government officials, judges, merchants, intellectuals, and other writers.

One of the best-known practitioners of this literary genre was a gifted story-teller by the name of al-Muhassin ibn Ali al-Tanukhi (d. 994) who lived in tenth-century Iraq, part of the Abbasid empire. Although trained and credentialed as a judge, al-Tanukhi gained renown for his adab works, the contents of which mirror the high intellectual and artistic accomplishments of his era. In his literary masterpiece titled Deliverance Follows Adversity, al-Tanukhi provides a rich miscellany of instructive information, wise anecdotes, and engaging folklore that illustrate how humans have achieved relief from distressing circumstances through time. Some of the stories border on the fabulous; many show the influence of Indian and Persian fables that also emphasize a common theme of humans earning deliverance from situations of calamity and hardship.

Al-Tanukhi also drew from his experiences as a judge who watched the drama of human life unfold before his eyes in the courtroom. He witnessed human suffering and failings on a regular basis, and his ability to bring some measure of relief and justice to the lives of the common people must have made a deep impression on him. A common motif in the stories that he included in his anthology is that of escape: humans escaping from the clutches of wild animals through sheer ingenuity, travelers outwitting robbers to escape their attacks, and poor people escaping from persistent creditors through fortuitous chance. Some anecdotes have a specific theological purpose, aiming to show how God works through human beings to bring deliverance to those who are needy, vulnerable, and in need of comfort. In our current world, held hostage by a deadly illness, these themes of escape and deliverance seem more poignantly relevant than ever. Through his miscellany of stories and reflections, al-Tanukhi encourages us to look on the positive side of life even when beset by misfortune, and to seek the silver lining that may be found for every cloud, if we look hard enough – advice that seems presciently appropriate for us, now that mass vaccination appears within reach in the near future.

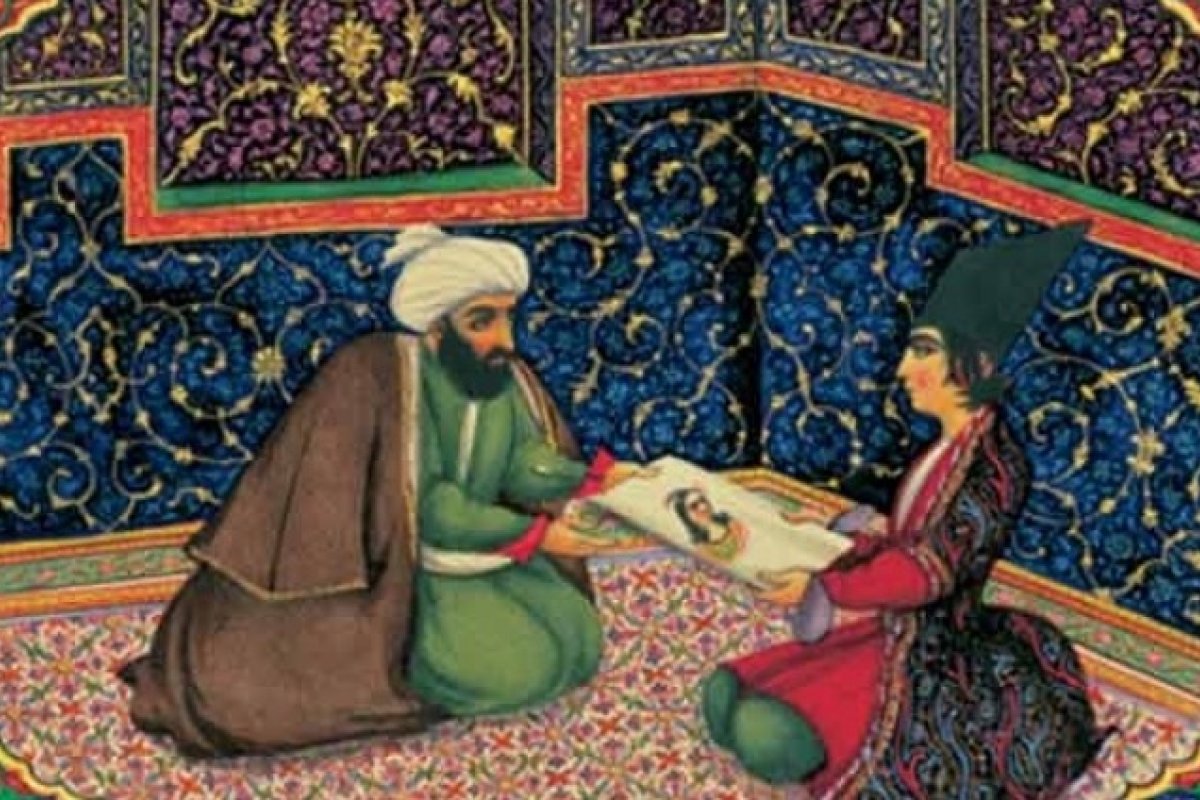

The success of this genre in Muslim literary circles prompted its adoption by some Jewish writers who lived in the Islamic world in the medieval period. One such writer was Nissim b. Jacob ben Nissim from the eleventh century, who lived in Qayrawan in North Africa. He wrote a Faraj ba’da al-shidda work in Judeo-Arabic, known by its Hebrew title Hibbur Yafeh me-ha-Yeshu'ah. The Relief after Misfortune genre also made its way into Ottoman Turkish literature by the fifteenth century and flourished there. The French Orientalist Antoine Galland incorporated some of these stories into his translation of The Thousand and One Nights (popularly known as Arabian Nights to English speakers), thereby introducing them to a European audience. Some of the engaging and ultimately optimistic stories included by al-Tanukhi in his literary masterpiece thus came to transcend cultural boundaries and travel far and wide, because they clearly resonated with the universal human desire to find solace in the midst of grief and to believe that happiness is attainable even after a most traumatic event.

No doubt, if al-Tanukhi were to be miraculously transported to our world today in the grip of a still-mysterious pandemic, he would sigh knowingly and say something like: Keep the faith, and remember that you can count on relief after misfortune!

[i] Toshihiko Izutsu, Ethico-Religious Concepts in the Qur’ān (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002), 45-54.

Image: "Scheherazade and the Sultan" (ca. 1850), illustration of the Thousand and One Nights by Iranian painter Sani ol Molk.

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.