Protesting Children

“How Young Is Too Young for Protest?”—an article by Stephanie Saul and Anemona Hartocollis in the New York Times published the day before the March 14 protest marches against gun violence in a great number of American high schools—posed questions which concentrated less on gun rights and more on the role of children on all sides of the guns-and-schools controversy

“How Young Is Too Young for Protest?”—an article by Stephanie Saul and Anemona Hartocollis in the New York Times published the day before the March 14 protest marches against gun violence in a great number of American high schools—posed questions which concentrated less on gun rights and more on the role of children on all sides of the guns-and-schools controversy. While formal religious arguments and incidents rarely make headlines, this incident has helped reveal fissures within the public where religious and ethical concerns were, and are, prime. These have to do with all the standard issues, and public attitudes by people of all ages. But this time there were good reasons to focus on concerns about children protesting, many of the young being prohibited from holding demonstrations.

“How Young Is Too Young for Protest?”—an article by Stephanie Saul and Anemona Hartocollis in the New York Times published the day before the March 14 protest marches against gun violence in a great number of American high schools—posed questions which concentrated less on gun rights and more on the role of children on all sides of the guns-and-schools controversy. While formal religious arguments and incidents rarely make headlines, this incident has helped reveal fissures within the public where religious and ethical concerns were, and are, prime. These have to do with all the standard issues, and public attitudes by people of all ages. But this time there were good reasons to focus on concerns about children protesting, many of the young being prohibited from holding demonstrations.

Without doubt, the March 14 walkouts and anti-walkout events will receive attention from leaders in churches and schools, public interest factions, activists, and ethicists. When young people awaken to a cause, many ordinarily passive and apathetic people get roused. Precedent for all this is the Birmingham Campaign for civil rights of April-May 1963. James Bevel, a leader in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, faced a decline in the number of adults who would participate in demonstrations to effect change. So he looked to a new front: those in high schools, colleges, and even elementary schools, teaching them the meaning of nonviolence and nonviolent actions. Arrests followed, but these first steps brought the “Children’s Crusade” and its cause to national attention. The rest, of course, is history.

Did the patently nonviolent protests and expressions on March 14 “make history,” and, if so, what kind of “making” lies ahead? Wyatt Tee Walker, a well-remembered civil rights leader with credentials, properly noted that the Birmingham student protests became a “legend,” and were the “most important chapter” in the entire civil rights movement. Is a new legend in the offing? Racism and racial tensions remain strong; they demand and deserve attention. Pro-gun and anti-gun forces are as polarized today as were the white citizens in Birmingham in the Sixties. While religion is a great motivator on all sides of these “legendary” changes, and while African American churches are prominent in the ongoing struggle for social justice, other formal religious institutions seemed to be less engaged in the recent Florida-and-then-national protests. Why they were not more engaged—if, indeed, such was the case—is a topic for a different day.

Back to the Saul-Hartocollis story, which takes us to Case Elementary School in Akron, Ohio, where a fifth-grade class drew focus for the dedicated way it mobilized. As students drew posters and walked out to march or stand in silence, protests against the protesting increased. Principal Danjile Henderson said that her “fifth-grade students were very aware of the details of the events and wanted to have their own peaceful protest.” She and her teachers treated those events in age-appropriate ways. The Times writers then admirably turn to many other schools, and give due attention to the many ethical and child-developmental issues that emerge.

Naïve indeed would be anyone who thought the legend of March 14 would match that of Birmingham in 1963. Why? Among other factors, the National Rifle Association mobilized and charted ways to oppose the nonviolent protest moves and movements. The Gun Owners of America, an NRA-type organization, urged its supporters to act: “We could win or lose the gun control battle in the next 96 hours,” read the group’s Twitter page. Things don’t happen that fast. But voices from the right have only begun to fight against the new efforts of the demonstrators following March 14, and they are well funded and fiercely motivated. Still, for one day, and perhaps one season, American citizens are at last hearing more voices than just the pro-gun ones, including those of the long-silent young.

Resources

- “Birmingham campaign.” Wikipedia. Accessed March 17, 2018.

- Contreras, Russell, and Noreen Nasir. “1968 LA school walkout protesters see link to Parkland teens.” Associated Press. March 12, 2018.

- González, Eloísa Ruano. “Sonoma County students join in national school walkout to protest gun violence.” The Press Democrat. March 14, 2018.

- Grenoble, Ryan. “School Walkouts Go Nationwide As Students Push For Gun Control.” HuffPost. February 21, 2018.

- Saul, Stephanie, and Anemona Hartocollis. “How Young Is Too Young for Protest? A National Gun-Violence Walkout Tests Schools.” The New York Times. March 13, 2018.

- Yee, Vivian, and Alan Blinder. “National School Walkout: Thousands Protest Against Gun Violence Across the U.S.” The New York Times. March 14, 2018.

Image: Students at Roosevelt High School in Des Moines, Iowa, join countless peers across the country in staging a school walkout to protest gun violence | Photo Credit: Phil Roeder/Flickr (cc)

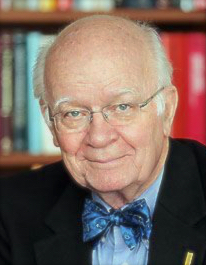

Author, Martin E. Marty (PhD’56), is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. Author, Martin E. Marty (PhD’56), is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco (AB’07, MDiv’10), a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.