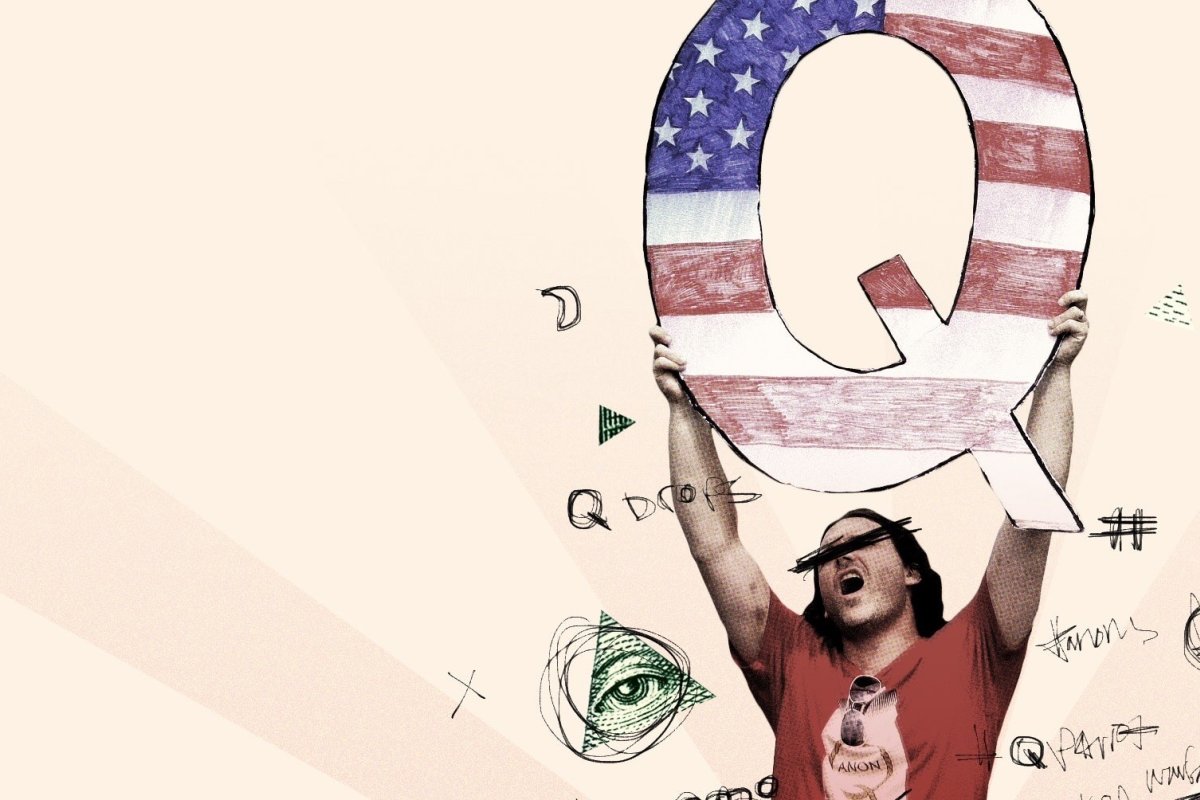

Playing the Ostrich; or, How Not to Think about QAnon

American conspiracy theories and the task of the scholar of religion

A recent article in The Atlantic, written by Adrienne LaFrance, engages in a lengthy examination of “QAnon,” the internet-based phenomenon that perceives a “deep state” within the U.S. government, against which the current President is in a clandestine war for the heart of the nation. The article’s premise is that to look at QAnon is to see not just a conspiracy theory at work—although it is that—but the birth of a new religion. The article supports this analysis by noting QAnon’s incipient apocalypticism (phrases such as “Nothing can stop what is coming” and “Trust the plan” are commonplaces on postings), along with its quasi-Manichean sorting of political figures as proponents of or antagonists to “the deep state” (a strictly partisan sorting, in which Democrats are figured as facilitators and Republicans—almost all of them—as antagonists).

The article reminded me of a much briefer essay, written by historian of religions Jonathan Z. Smith, on the communal suicide orchestrated by the Reverend Jim Jones at the People’s Temple in Jonestown, Guyana, in 1978. Smith’s chastising essay is less concerned with the particulars of that awful event, and more with the failure of scholars of religion to acknowledge the event as within the purview of the study of religion. Smith identified in this failure the default tendency of the scholarly community to make “religion” what the particular scholar regarded as “good religion,” and in turn to ignore its implicit counterpart, “bad religion.” Papers and books on the textual traditions, histories, and thought of Christianity (especially), Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and Hinduism proceeded apace; even as this halcyon event, involving a syncretistic ritual and mass death, was passed over with virtually no comment.

I must acknowledge that, even with Smith’s admonition in mind, I have a strong preference to play the ostrich when it comes to QAnon.

There is a problem, however, with digging a hole and sticking my scholarly head inside it. It is the empirical reality that, if not QAnon, the likes of QAnon are not going away anytime soon. Unless I can breathe endlessly underground, I shall have to emerge from my self-imposed denial. When I do, I’ll find that what I had hoped to avoid is still around. There is the related, even more pressing consideration of QAnon’s role in American public life, and whether its presence is conducive, or not conducive, to America’s deliberative culture.

So I would begin by augmenting the premise of the Atlantic story and note other ways in which QAnon clearly borrows from religious traditions, chiefly those of American Christianity, to forge its ostensible worldview. Pivotal to QAnon is its premise that there is a worldwide, systemic slaughter of innocent children (a reader of the QAnon postings was responsible for “Pizzagate,” the baseless claim that former Secretary of State and Democratic Presidential nominee Hillary Clinton was running a sweatshop for children at a pizza house in Washington, D.C.). QAnon writers both appropriate biblical verses (e.g., the Epistle to the Ephesians, “put on the full armor of God”) and engage in debates about the meaning of the words and even the gestures of public officials to discern covert signals about the unfolding plan to defeat “the deep state.” When queried for evidence in support of these claims, interviewees characteristically respond, “Do the research.” The slaughter of the innocents, the citations of the Bible, the discovery and interpretation of signs of the times, the relation of esoteric knowledge to exoteric query—these are all recognizably religious themes and practices. QAnon’s followers also predict a Great Awakening and salvation in a future when the deep state is finally defeated. QAnon adopts common motifs of American religion and its history to articulate their worldview. Either you get it, or you don’t—and whether you do or don’t has ultimate consequences.

While the Atlantic article heeds Smith’s excellent counsel about not putting our heads in the ground, the article (and for that matter, Smith) is less helpful when it comes to offering an assessment of what to do when, heads in the air, we see what is happening. The Atlantic article provides analogies: the nineteenth-century Millerites and their subsequent reconfiguration as the Seventh-Day Adventists; Senator Joseph McCarthy’s efforts (in the House Un-American Activities Committee of the 1950s); and anti-Semitism (many venues, many eras, many nations).

The causal logic of these analogies seems to be that QAnon engages in a “mass rejection of reason and Enlightenment values” and that, through this rejection, it qualifies as a religion. Religion is thus predicated in the article as premodern and anti-rational. I would suggest that this is another, far too common mode of playing the ostrich. It certainly won’t do what its author wishes—to make QAnon go away—and it does very little to acknowledge the complex and sophisticated way in which religions during and in the aftermath of the Enlightenment engage, indeed function, as “modern” and “rational”—for good and for ill, to be clear. Scholars of religion as different in temperament as James Barr, Martin E. Marty and R. Scott Appleby, and Saba Mahmood argue powerfully and persuasively against the assumption of the Atlantic article. Different in temperament and focus as these scholars are, none of them play the ostrich about disturbances in the religious field. Each would be dubious about the assumptions that control the Atlantic discussion of QAnon.

That QAnon plays a role in American public life seems to be beyond question. To face it down is to ask whether it should have such a place. To answer that requires two complementary acts. One is that QAnon has to offer reasons for their views that do not simply cohere to internal self-understandings, but that are publicly coherent and defensible. So far as I can discern, in this they have failed, comprehensively and even obdurately. The other is that those who recognize this failure must refuse to play the ostrich and name this failure for what it is. In this latter task, the Atlantic article falls short. Not to hold religion to account—whether as practitioner, observer, or both—is to make religion the ongoing handmaiden to an exceptionalism that has been and can only be a detriment to public life and deliberative culture.

Image Credits: Photo by Rick Loomis; Illustration by Elena Lacey.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.