Of Memphis and Washington

White Supremacy's desecration of sacred spaces, in 1968 and today

On this day of remembrance, so close on the heels of the unprecedented assault on our nation’s capitol, let us begin by remembering that Dr. King’s presence in Memphis, Tennessee on the night of his assassination was a return visit. The details are worth rehearsing, if only to remind us of how astonishing the recent events of January 6 were in comparison, and how paltry the justifications offered by the latter’s delusional advocates.

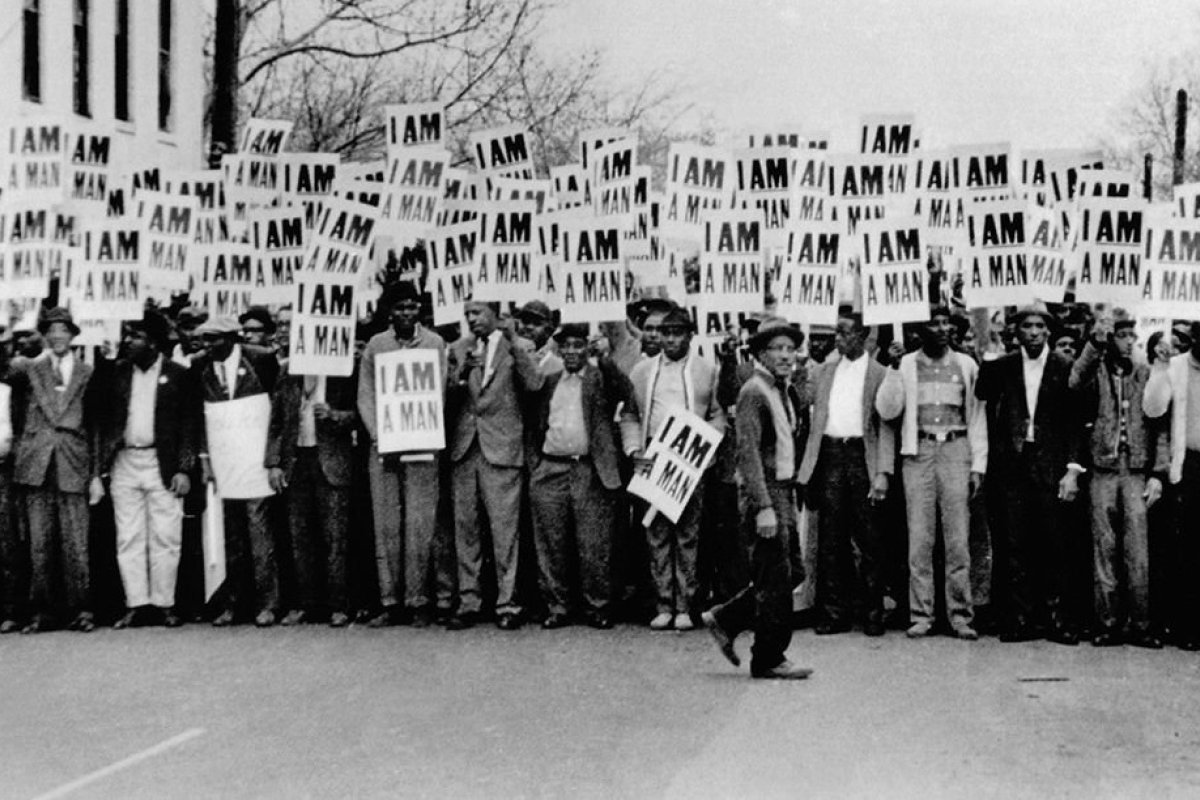

As part of his Poor People’s Campaign, Reverend King had sought to bring to nationwide attention the plight of sanitation workers in Memphis. In February of 1968, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, garbage collectors for the city, had been crushed to death by a malfunctioning truck; later in the month, over one thousand Black men employed by the Memphis Department of Public Works went on strike to protest their deaths as the latest in a series of events reflecting neglect and abuse of Black employees. They requested recognition of their union, improved safety standards, and an increase in the minimum wage for their labor (many full-time employees had to take welfare and food stamps to feed their families).

Earlier protests had not garnered community support. Memphis’s newly elected mayor, Henry Loeb, proved indifferent to these requests, spurring the workers’ decision to strike. Their action was endorsed by the N.A.A.C.P., and a subsequent sit-in by sanitation workers at City Hall resulted in a resolution by the Memphis City Council to recognize the union and increase wages. Mayor Loeb, however, rejected the Council’s resolution on the grounds that he alone had the authority to take such action, and indeed stated that he would not. These events galvanized local residents, including churches and also high school and college students, who organized a series of marches to call attention to the situation and to protest the Mayor’s decision.

We know that King was monitoring the situation closely and decided to offer support by visiting Memphis. When he arrived on March 18, he addressed the largest indoor gathering the Civil Rights movement had seen to date – estimated at 25,000 people. Reiterating his earlier admonition that we are all "tied in a single garment of destiny,” he exhorted a city-wide work stoppage to support the sanitation strike, including a peaceful protest march to be organized in the next few days and that he promised to lead.

When King returned to lead the march, the gathered crowd was significantly larger than the one he had addressed just days earlier, and it was by common report disorganized and included people inclined to violent action. There was and remains debate about the causes of the temper of the crowd, but what is clear is that King quickly concluded that it was not the right moment to march and cancelled the protest. To King’s considerable distress, there was subsequently looting of downtown stores, during which a police officer shot and killed a sixteen-year-old boy. Memphis police pursued protesters to a sacred space, the sanctuary of the Clayborn Temple, where they released tear gas and then clubbed protesters as they lay on the floor attempting to get fresh air into their lungs. Mayor Loeb called for martial law and speedily secured the presence of 4,000 National Guard troops.

King publicly blamed himself for failing to understand the complexities within the protesting community and condemned both the shooting and the looting. Local protests continued and there was significant debate within King’s inner circle regarding what, if anything, he should now do. Over the stringent objections of some advisers, King decided to return to Memphis in early April for a second visit. His decision was prompted by his distress that the original visit’s purpose—to support the efforts of garbage collectors to unionize—had concluded with acts of vandalism that he regarded as intrinsically unacceptable and contradictory to the cause of justice. He returned to Memphis determined to see that his movement not only could but would do better: that it could advocate fervently and peacefully for its cause. This decision ended in his assassination by white supremacist James Earl Ray on the night of April 4th at the Lorraine Hotel.

To be sure, fifty-two years allow for a greater degree of retrospective clarity than ten days. Still, some very clear contrasts are manifest and merit rehearsal. We lack a full accounting of the participants, much less a coherent statement of the cause for the siege of our nation’s Capitol on January 6. What is abundantly clear, however, is that if they return, it will not be to correct excesses (which were the point, rather than incidental) but to enhance them. March 1968 in Memphis sought through peaceful protest to change the compensation and benefits of public servants. January 2021 in Washington, D.C., sought through violence to overturn the legitimate results of the national election of the President, and in the process to kill public servants.

Not incidentally, the contrast between Reverend King and the current President could not be more complete. Where King inspired listeners, Trump incited them (and then retreated to the sanctuary of the Oval Office to view their subsequent actions). At Memphis an exhausted King spoke of his mortality and the conclusion of his journey; in Washington, the President speaks of the outrages against him and of the good people who support him, all the while planning his exit strategy as Covid-19 rages across the country. None of the hallmarks of Dr. King’s witness—its heroism, its invocation of solidarity, its willingness to put one’s life on the line for the ideal—can be detected in the current President’s behavior.

King’s purposes, and the factors motivating his presence in Memphis, are entirely clear. The rioters who stormed the Capitol, by contrast, seem driven by a perfect storm of motivations circling around an inchoate distrust of “the government” focalized in the results of November’s election but extending to threats of murder and the erection of a nearby lynching station. In addition, the rioters who laid siege to the Capitol building were, to a very large degree, white rather than black and brown Americans. Unlike the vast majority of the protesters in Memphis, their uniformly adopted means were explicitly, even celebratorily, violent. Why these rioters were not all forced into the sanctuary of the Capitol, tear gassed, and then beaten on the ground while they gasped for air is an inescapable question when one recalls the events in Memphis.

The language of “desecration” was a hallmark in reporting the events of January 6th, accompanied by references to the Capitol as “the temple of democracy.” I thought I glimpsed in these words dual, perhaps complementary, motivations: an attempt to characterize the scale of the violation, and the sense that democracy requires a degree of reverence, a kind of political faith, for its survival. As the story of Memphis underscores, however, such a sense of violation, and such a degree of reverence, continue to be at once necessary yet vexingly fleeting in our modern democratic experiment. To recover or to create anew such reverence and faith will require return visits, ongoing confrontations with the demons that always lurk near America’s door.

Photo: The sanitation worker's march on March 28, 1968, in Memphis. (Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr., courtesy of the Withers Family Trust)

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.