Longing for a Real Thanksgiving

This year's lonely holiday offers a chance for national repentance

…I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States… to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.

—President Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation of Thanksgiving, Oct 3, 1863

Like most other aspects of our national life in 2020, today’s Thanksgiving holiday is a marked departure from our comfortable routines and cherished memories. The autumn surge in COVID infections has crested just in time to interrupt the annual festivities that stave off winter’s darkness by gathering loved ones close: Thanksgiving, Hanukkah, Christmas, Kwanzaa. Escalating case counts, hospitalizations, and deaths have prompted mayors, public health officials and medical professionals to offer stern guidance in anticipation of the holiday season: “don’t do it.” Don’t travel. Don’t gather at grandma’s house. Don’t congregate inside houses, at all – set the table in the garage, or the back yard. Feast only with those who dine with you daily, the members of your immediate household. To be on the safe side, “Cancel Thanksgiving,” advises a recent issue of The Atlantic.

In keeping with the fractious spirit of our times, this particular piece of pandemic pedagogy has not been universally embraced. Families who vowed only a month ago not to argue about politics over the Thanksgiving turkey have engaged instead in heated disagreements about the viability of the observance itself. The tension between worldviews manifest in our recent elections is recapitulated in family Zoom sessions, phone calls and email exchanges, as parents and siblings negotiate new expressions of family ritual at a moment in which so many meanings and priorities have been upended. Is Aunt Jane an extremist if she declines to gather with the family this year out of concern for her health or that of others? Is cousin Jack behaving irresponsibly if he is determined to travel cross-country to reunite with loved ones? Yet again, this dystopian season reveals uncomfortable truths about the complicated tides of ambiguity and ambivalence that human beings must always navigate. Our inherited wisdom is subject to circumstance; our studied judgment is myopic at best; our cherished traditions cannot provide sure shelter from the storms of change; even our best efforts to care for one another can cause pain or discomfort to those we love, and to all whose lives are contingent upon our own.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that we have approached this Thanksgiving with anxiety and fear, especially hungry for the deep reassurance of the family table. We rely on these gatherings—their institutions, narratives and rituals—to help us mediate the complicated and contradictory experiences that are at the heart of human being, knowing and doing. For generations rituals of gratitude, in particular, have helped societies manage ambiguity and metabolize the loss and grief that are the shadow side of our desires for love and power. The ancient prophets and sages whose teachings still inform our life together invite lamentation and demand repentance before supplicants’ thanks-givings may be received. Long before the arrival of Europeans on our continent, its inhabitants understood and honored their debt to forces beyond their control—sun, rain, soil, and oceans—that allowed the people’s flourishing, or not. In the early days of our nation, colonists were often called to “Thank Days,” actively engaging in prayerful reflection when life seemed particularly tenuous, and their own contingency demanded sober acknowledgement.

Just a few months into his presidency, deep into the work of ratifying a constitution that would build a republic from wrangling colonists, George Washington called for a national day of thanks to be observed on the 26th of November. In a proclamation issued on Oct. 3, 1789, he called fellow citizens to “unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions; to enable us all, whether in public or private stations, to perform our several and relative duties properly and punctually; to render our national government a blessing to all the people, by constantly being a Government of wise, just, and constitutional laws, discreetly and faithfully executed and obeyed…”

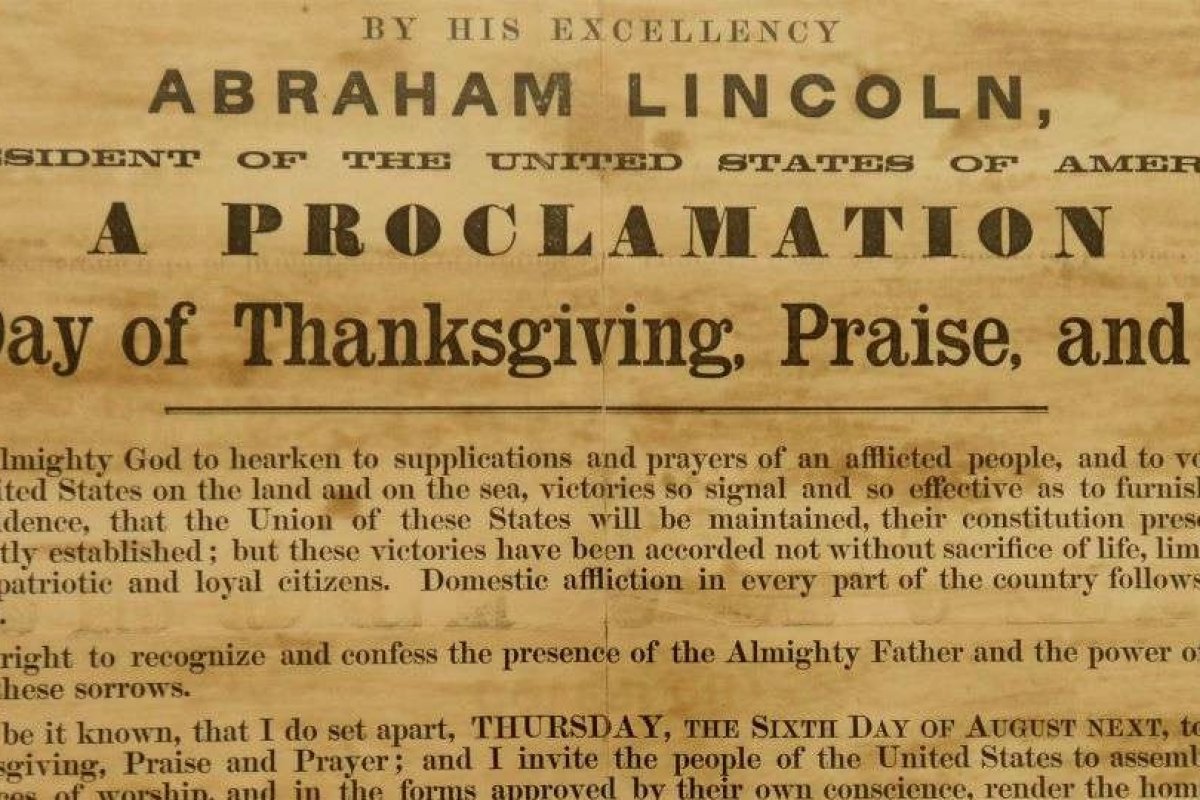

Abraham Lincoln’s better-known 1863 Thanksgiving Proclamation, emerging from the depths of the Civil War, was issued on the same day as Washington’s—October 3—and marked the same Thanksgiving Day, Thursday, November 26. Significantly, the 16th president’s call to thanksgiving also referenced the same complex sensibilities named by his predecessor: the troubling ambiguity and terrible cost involved in human project of nation-building. Lincoln called citizens to offer thanks in the midst of the country’s paroxysm of anger, fear, and grief. Such gratitude demanded humility and repentance, and was not aimed only to provide an occasion for counting one’s blessings, or celebrating individual successes, but to orient the community towards a renewed sense of solidarity, and to turn its desires and its prayers towards “peace, harmony, tranquility, and Union.”

In our own time, of course, many Americans respond with cynicism and distrust when our leaders appropriate religious language to ameliorate pain and discord in seasons of national crisis. But our contemporary political boilerplate, “God bless America,” bears little resemblance to these proclamations of our forebears that engage in confessing before requesting a blessing. As of this writing, our own president has not made a Thanksgiving proclamation, opting instead to record a proclamation that this week, November 22-28, be designated “national family week.” Four of the proclamation’s six paragraphs reproduce the campaign rhetoric that is characteristic of this president’s communication and his main concern—the words “I”, “my” and “we” appear over a dozen times. There is no acknowledgment of brokenness, no call to repentance. The word thanksgiving appears once, in a sentiment bent on flattery and self-congratulation: “In this season of Thanksgiving, we thank God for the wonderful families across our great Nation who are working to build brighter, better, and more prosperous futures.”

We are not wrong, in a year marked by uncertainty, unrest, and the twin pandemics of disease and racism, to long for a “real Thanksgiving.” Perhaps that very longing speaks volumes about the power of rituals that can hold us as we mourn alongside the quarter of a million families whose Thanksgiving gatherings are forever changed by the loss of a loved one to COVID-19, as we repent of the fear and distrust that separates families and communities and cultures from one another, and as we humble ourselves in preparation for the work of healing and rebuilding broken lives, broken cities, broken trust. Perhaps this quiet Thanksgiving—this unaccustomed Thanksgiving—this Thanksgiving spent in remembrance, and longing, and listening for what light and wisdom might yet come from our present trouble—perhaps this is indeed the Thanksgiving we need.

Image: Lincoln's 1863 Thanksgiving Proclamation, courtesy of The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.