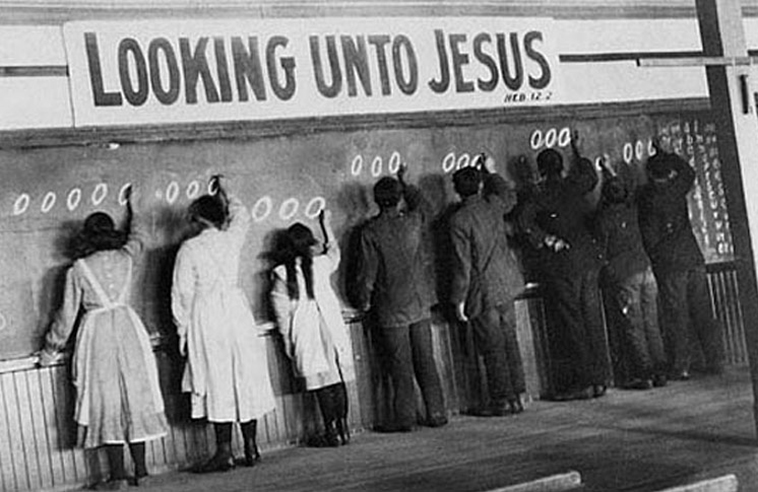

"Kill the Indian in the Child"

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has verified reports and testimony by survivors—they do not call themselves “graduates” or “alumni”—of First Nations schools, whose mission had long been announced: “kill the Indian in the child.” Following official policy, thousands of children were “taken out of their communities and away from their families” and sent to schools where they were to be forcibly “converted” or “civilized” into Canadian society

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has verified reports and testimony by survivors—they do not call themselves “graduates” or “alumni”—of First Nations schools, whose mission had long been announced: “kill the Indian in the child.” Following official policy, thousands of children were “taken out of their communities and away from their families” and sent to schools where they were to be forcibly “converted” or “civilized” into Canadian society. The survivors of the Shubenacadie Residential School told of how they had been “beaten,” “starved and locked up in cabinets,” recalling their “constant hunger and fear” and virtual slavery “in kitchens and laundries and at farm labor.” Many attempted to flee, though few escaped. Some died from injuries resulting from their cruel treatment.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has verified reports and testimony by survivors—they do not call themselves “graduates” or “alumni”—of First Nations schools, whose mission had long been announced: “kill the Indian in the child.” Following official policy, thousands of children were “taken out of their communities and away from their families” and sent to schools where they were to be forcibly “converted” or “civilized” into Canadian society. The survivors of the Shubenacadie Residential School told of how they had been “beaten,” “starved and locked up in cabinets,” recalling their “constant hunger and fear” and virtual slavery “in kitchens and laundries and at farm labor.” Many attempted to flee, though few escaped. Some died from injuries resulting from their cruel treatment.

We touched on the painful history and legacy of Canada’s residential schools for Native people in a recent Sightings column. So common are such stories, from many different cultures, that one can grow numb to them. Still, they demand our attention. Read, for example, Eileen Markey’s “The reckoning: Canadians, and Catholic religious orders, grapple with a history of ‘whitewashing’ indigenous children” (America, June 25 issue). The author provides an account of some of the residential schooling policies that were encouraged by the Canadian government.

One passage, in particular, immediately became locked in my mind and memory. Testifiers “told of being 5 or 6 years old and jeered at for wetting their beds, forced to carry their urine-soaked sheets on their heads through the dining room, their bare bottoms exposed in hospital gowns. There was sexual abuse.” Bringing up these horrors up north is not to isolate, attack, or pick on Canada, Catholic religious orders, or specific schools. In fact, Canada is doing better than some other nations—which shall remain unnamed here—whose leaders seem less interested in pursuing Truth or Reconciliation. Let us focus, instead, on a theological-political point that deserves to be sighted.

A question stands out: what can we learn from the people and incidents in Markey’s America magazine article, and from their, and her, calls for repentance, which—as so often in my use of that term—requires a “change of heart,” and then action? Sister Joan O’Keefe, president of the Sisters of Charity of Halifax, asks readers to dwell on this: “My goal is to continue to build … relationships and to respond to the invitation to be part of the process.” She continues: “We colluded in a racist system … It’s not enough to ask for forgiveness. The point is to listen to their stories … You can’t reconcile if you don’t know the truth.”

Catherine Martin, a Mi’kmaw woman who is a leader in this cause, observes: “The work and the time that is required for healing … will take the rest of the lives of those who were abused and those who abused and the rest of the lives of the people who inherited the aftereffects.” (Newsy side note: think of those children in “our” slave-kingdom, recently uprooted from their own families as a result of our government policies and practices.) Father Robert Schreiter, my neighbor in Chicago and professor of theology at the Catholic Theological Union, says of the Canadian project—which he helps to lead: “What we’re trying to do in a social reconciliation is not change the past but change our relationship with the past … In a sense it reverses time.”

The priest adds: “It was actually the theology that was violent … We need to look at the theology that blinded us and prevented us from seeing.” The “root sin” in the residential school system—which “made everything else possible”—“was the lie that European and Christian culture was superior to First Nations’ cultures.” May this Canadian story be helpful to anyone who would cherish the truth that people should be free wherever, and under whatever tribal names or religious auspices, they live.

Photo Credit: United Church of Canada Archives

Martin E. Marty (PhD’56) is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. Martin E. Marty (PhD’56) is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco (PhD’18). Sign up here to get Sightings by email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.