“It Is Music That Lifts Us Up from the Earth at the Very Moment of Death”: On the Transcendence of the Popular

Editor's Note: This essay is the final installment in our six-part series on religion and popular music

Editor's Note: This essay is the final installment in our six-part series on religion and popular music. The previous issues were "The Broken Grace of Leonard Cohen" by Paul DeCamp (April 13); "Being Hip-Hop, Being Job, and Being" by Julian DeShazier (May 4); "'No One Was Saved': The Beatles and Organized Religion" by Kenneth Womack (June 1); "Of Music and Martyrdom" by Nika Roza Danilova (June 22); and "Finding Evidence: Bruce Springsteen's Procession from Religion to Faith" by Eileen Chapman and Eileen Reinhard (July 20). Special thanks to all of our contributors!

“Sacred song is for the masses.” With this simple assertion in the 46th letter of his Theologische Schriften (1780/81), Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) drew together his writings on song and music from the 1770s, a remarkable series of volumes that channeled the histories of sacred and secular music from throughout the world into the common discourses of what he would call, for the first time, Volkslieder, “folk songs.” Turning his attention first to gathering “ancient songs” from history (in Alte Volkslieder, an unpublished manuscript from 1774) to an aesthetic exegesis of the biblical Song of Songs to the first German-language retrieval and translation of the Sanskrit Bhagavad Gita to the two volumes of Volkslieder at the end of the decade and beyond to his magisterial study, Vom Geist der ebräischen Poesie, which established the musicality of the Bible, Herder would alter the course of the history of popular music, from the late Enlightenment to our own day.

“Sacred song is for the masses.” With this simple assertion in the 46th letter of his Theologische Schriften (1780/81), Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) drew together his writings on song and music from the 1770s, a remarkable series of volumes that channeled the histories of sacred and secular music from throughout the world into the common discourses of what he would call, for the first time, Volkslieder, “folk songs.” Turning his attention first to gathering “ancient songs” from history (in Alte Volkslieder, an unpublished manuscript from 1774) to an aesthetic exegesis of the biblical Song of Songs to the first German-language retrieval and translation of the Sanskrit Bhagavad Gita to the two volumes of Volkslieder at the end of the decade and beyond to his magisterial study, Vom Geist der ebräischen Poesie, which established the musicality of the Bible, Herder would alter the course of the history of popular music, from the late Enlightenment to our own day.

Herder’s concern was to move toward an ontology of music arising from human experiences across time and space, the vox populi, sounding what he famously described as “the voices of the people in song.” Herder called popular music into being. And he did so not only as a philosopher and anthropologist, but also as a theologian and a pastor, who served the Protestant community of Weimar during the closing decades of his life.

With this brief introduction of Herder as the first scholar to reconnoiter the subject area shared by these essays on religion and popular music in Sightings I do not mean to reroute the series by shifting its historical focus by two centuries. Rather than narrowing the focus on the invention of popular music by a theologian, I seize the opportunity of this essay to broaden the focus, as did Herder, to search for religion in popular music on a global soundscape, freeing it from the purview of the privileged and allowing it to resound through the diversity of the masses.

For Herder, such refocusing was a response to theological motivations, and in this essay it is for me as well. In my teaching and research as an ethnomusicologist the sacred and the popular frequently—I might even say, insistently—converge. To understand American hymnody, for example, I have found it necessary to explore sacred song as a mass phenomenon, in which the hymns of Isaac Watts, or the shape-note hymns of the Sacred Harp, or the gospel hymns of Thomas A. Dorsey circulated widely and left a lasting impact on American popular culture. The very concept of a hymn, which draws the many rather than the few into active participation in a religious service, relies on the aesthetics of popular music: texts with meaning for the individual’s life; melodic and harmonic forms that give voice to the collective of worshipers; adaptability over time; the capacity to change; and, above all, making extensive use of covers.

I could easily adapt these criteria to the hermeneutic analysis of Tin Pan Alley or the fusion of folk and popular music during the Folk Music Revival. Just as easily, I could—and often I do—employ these criteria when studying religious musics in cultures other than those of North America. Over the course of the past quarter-century, for example, I have studied the music of pilgrimage, joining pilgrims on their journeys in Central and Eastern Europe, and in the Middle East and South Asia. Hindu bhajans or the songs fused into Muslim qawwali in India, to take well-known examples, require, but also inspire, the mass participation of pilgrims on the path toward or worshiping at shrines. As popular music, these religious songs are disseminated through every available and effective medium, from pamphlets filled with prayers to audiocassettes and CDs to Bollywood films.

Sacred popular music, local and global, is notable for its newness. Its efficacy lies in an ability to attract worshipers across the generations, but above all from a younger generation that has grown up in a youth culture in which the borders between the secular and the sacred are indistinct. Just as hip-hop became a cross-cultural and multilingual popular-music phenomenon at the end of the 20th century, so too has it become a stylistic medium borrowed for a multitude of religious purposes in the 21st. Jewish hip-hop, with internationally renowned Hassidic performers such as Matisyahu, moves across a vast landscape of Jewish subjects and resituates them in popular culture by addressing central issues of Jewishness. In the revival of several forms of Buddhism in East Asia, especially in Taiwan and mainland China, popular music and dance styles have engendered new sites for the celebration of ritual and engaged young Chinese Buddhists from sectors of society long regarded as secular.

One of the striking themes running through the essays that preceded mine in this Sightings series on religion and popular music has been for me the way in which religion, in content and practice, appeared in unexpected places, and paradoxically so. In the space remaining for me in the present essay, I should like myself to contribute to this theme, and I do so by drawing on my own ethnographic studies and turning to the largest single event in popular music worldwide: the Eurovision Song Contest. First staged in Switzerland in 1956, the Eurovision was an attempt to ameliorate rising political and military tensions at the height of the Cold War. Preparations for the annual event take place during the course of an entire year, leading to the grand final in May, which is broadcast internationally to live audiences that exceed 200,000 in many estimates. As a spectacle of popular culture and popular music, it stands alone. The Eurovision has expanded internationally each year until the present, adding new countries: at the end of the Cold War the nations of Eastern Europe, and in recent years an increasing number of nations that are not part of Europe, most recently Australia in 2015. For the past decade, an average of ca. 43 nations compete each year. Claims that Americans know little about the Eurovision are revisited and revised each year, especially since it is now possible to follow the events online.

The largest international spectacle of popular music and politics—nations compete against each other—would seemingly leave little room for religion, at least according to many observers. Whether because of the Cold War Realpolitik of a division between the Christian West and non-religious East, or because of the fear of Islam on the borders with the Mediterranean and western Asia, religion was largely absent in the popular parsing of Europe by the European Broadcasting Union, which organized the contest. Religious tensions were many, in local tensions on Cyprus, or in Ireland and Israel, and in the growing number of primarily Muslim countries—Albania, Azerbaijan, and Turkey, to name a few—as well as countries with diverse Muslim and other non-Christian populations.

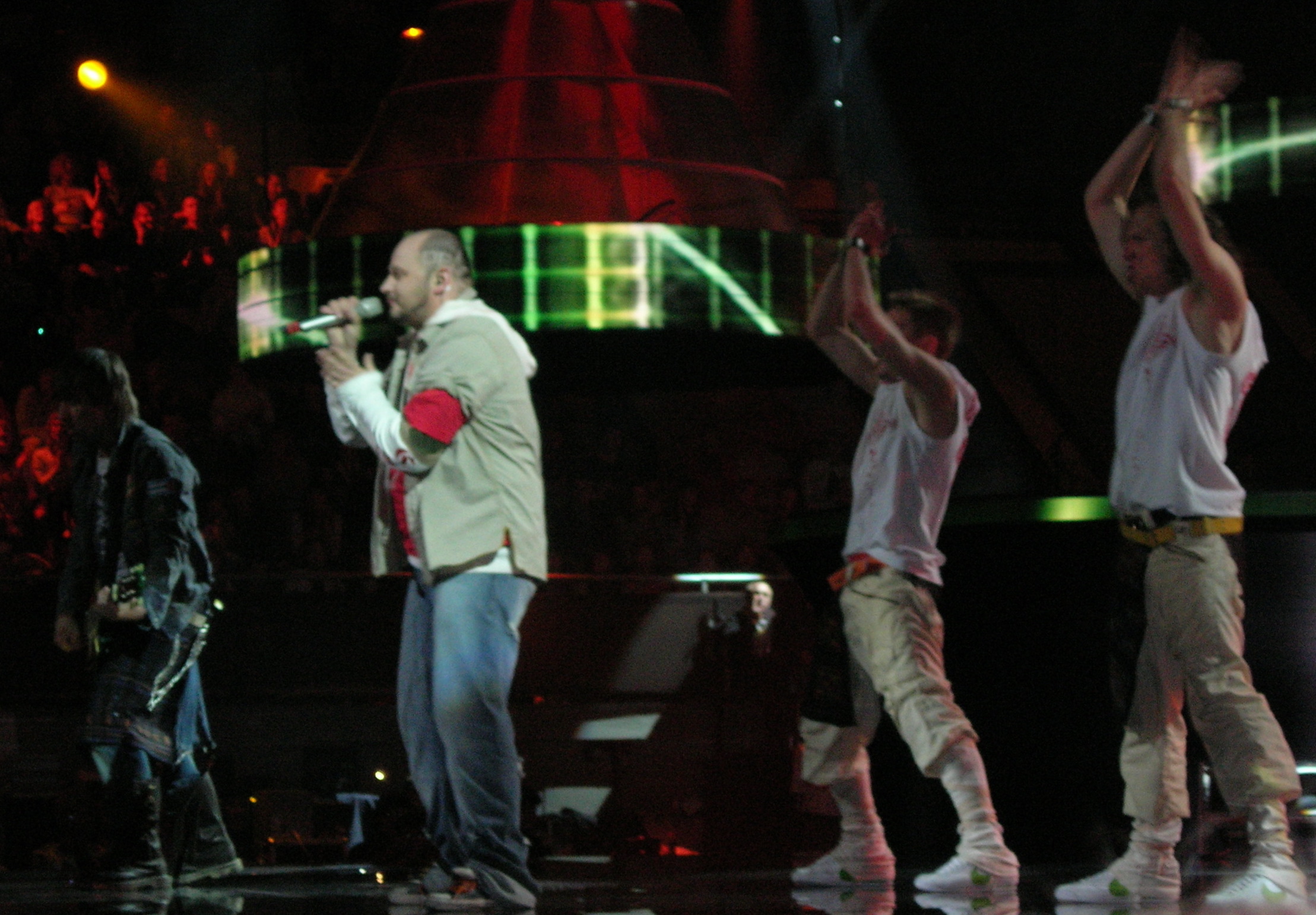

Religion did not, however, disappear from the imagination of European unity, but rather it reasserted its presence together with popular music. Religious themes have both direct and indirect forms in Eurovision songs, which is to say, song style and performance possibilities realize the ways in which religion gives voice to the people. There are songs that openly express religious themes. This was the case, for example, with the winning songs in the three consecutive years, 2006–8: Finland’s Lordi performing “Hard Rock Hallelujah” (heavy-metal); Serbia’s Marija Šerifović singing “Molitva” (“Prayer”; sevdalinka-style from the Ottoman ecumene); and Russia’s Dima Bilan performing “Believe” (Europop). There are songs that contain references to religion as identity, but express that identity subtly or overtly. References to Islamic musical styles—for example, use of Middle Eastern instruments—take place in the “bridge,” or “Middle Eight” section of the common popular-song style (AABA). Countries such as Armenia and Israel allow little equivocation when they integrate religious themes into lyrics and song form.

Critical to the ways in which religion enhances the presence of popular music in the Eurovision is that it is not ubiquitous. As a signifier of meaning its power accrues because of its specificity. As an exception, it highlights the exceptional. It was this power of religion, too, that Johann Gottfried Herder recognized when he gathered songs in anthologies, placing the religious next to the non-religious. No longer separated by time and place, joined instead to give voice to the many rather than the few, opening a moment coterminous for the sacred and the secular, popular music and religion converged to unleash a new transcendence. He believed—and he would hope we, too, might have inherited his sensibilities—that music and religion would enter the lives of all humanity in more powerful ways. It was to this belief that he returned again and again, underscoring it in the final sentence he would write on music, the conclusion of his essay, “On Music,” in 1800: “As we know so very well, it is music that lifts us up from the earth at the very moment of death.”

Resources

- Engelhardt, Jeffers, and Philip V. Bohlman, eds. Resounding Transcendence: Transitions in Music, Religion, and Ritual. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Herder, Johann Gottfried, and Philip V. Bohlman. Song Loves the Masses: Herder on Music and Nationalism. University of California Press, 2017.

- Tragaki, Dafni, ed. Empire of Song: Europe and Nation in the Eurovision Song Contest. Scarecrow Press, 2013.

- The official Eurovision Song Contest website: http://www.eurovision.tv/

Author, Philip V. Bohlman, is Ludwig Rosenberger Distinguished Service Professor in Jewish History in the Department of Music and in the College, and an associated faculty member of the Divinity School. At Chicago he is also the artistic director of The New Budapest Orpheum Society, a Jewish cabaret that is ensemble-in-residence at the Humanities Division. His research on music and religion ranges widely and includes Jewish music, music and Islam, vernacular sacred music in North America, and South Asian religious practice. His most recent work on music and religion includes Wie sängen wir Seinen Gesang auf dem Boden der Fremde: Jüdische Musik zwischen Aschkenas und Moderne (LIT Verlag, 2017) and the Grammy-nominated CD As Dreams Fall Apart: The Golden Age of Jewish Stage and Film Music, 1925–1955 (Cedille Records, 2014). Author, Philip V. Bohlman, is Ludwig Rosenberger Distinguished Service Professor in Jewish History in the Department of Music and in the College, and an associated faculty member of the Divinity School. At Chicago he is also the artistic director of The New Budapest Orpheum Society, a Jewish cabaret that is ensemble-in-residence at the Humanities Division. His research on music and religion ranges widely and includes Jewish music, music and Islam, vernacular sacred music in North America, and South Asian religious practice. His most recent work on music and religion includes Wie sängen wir Seinen Gesang auf dem Boden der Fremde: Jüdische Musik zwischen Aschkenas und Moderne (LIT Verlag, 2017) and the Grammy-nominated CD As Dreams Fall Apart: The Golden Age of Jewish Stage and Film Music, 1925–1955 (Cedille Records, 2014). |

SIGHTINGS is edited by Brett Colasacco (AB’07, MDiv’10), a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Sign up here to receive SIGHTINGS via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.