Hip Hop and Christian Conversion Narratives

What do Kanye and Hip Hop have to do with Augustine of Hippo?

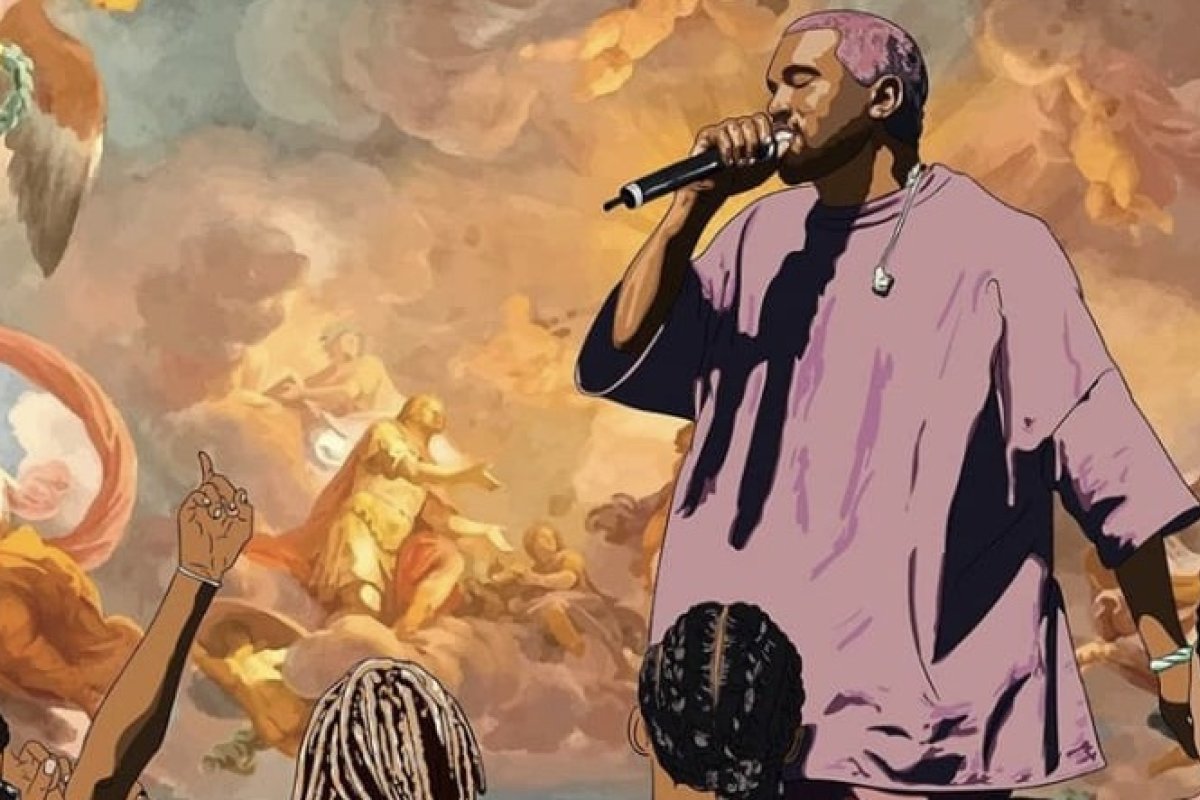

In 2013, Kanye West released the album Yeezus, the title of which combined Kanye’s nickname—Yeezy—and Jesus. Among the tracks on the album was a song entitled “I am a God.” The allusions were rather heavy-handed: Kanye portrayed himself in terms of a demigod.

Six years later, Kanye released Jesus is King. Radically diverging from his previous works, the album is replete with biblical references, gospel choirs, and songs such as “Jesus is Lord” and “Follow God.” According to Kanye, the album is a hip-hop account of his religious conversion to Christianity: “This album has been made to be an expression of the gospel and to share the gospel and the truth of what Jesus has done to me.”

Kanye’s religious conversion sparked a variety of reactions. Some celebrated. Some cringed. But all were curious.

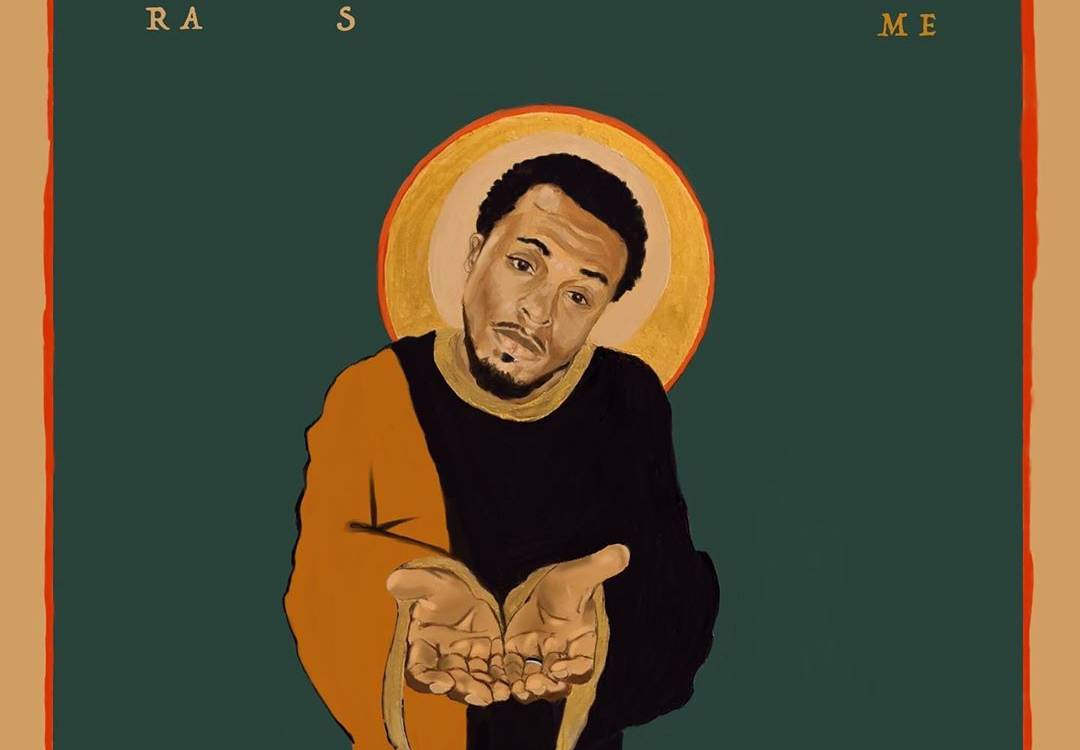

Last week, the Christian rapper Flame released a new album, Extra Nos, chronicling his theological conversion from Calvinism to Lutheranism. (Some might remember that Flame made headlines in July 2019 after winning a copyright infringement lawsuit alleging that Katy Perry had wrongfully copied elements from his song, “Joyful Noise.”)

Flame’s newest album includes a shout-out to a theology professor, intricate doctrinal distinctions, and copious amounts of Latin. For example, Flame raps about his journey away from Calvinism on a track titled “Scattered Tulips”: “I see scattered tulips, Come with me I’ll show you what I found, I be diggin' in the text, Funny what you find when you low to the ground.”

Hip hop has proven fertile ground for the telling of Christian conversion stories. And these artists and albums are deserving of a place in the long tradition of Christian conversion narratives. In fact, these hip-hop albums simultaneously draw from and seek to transform this tradition. Where conversion stories were once only shared orally or in print, they are now disseminated through a multitude of new media. These multimodal conversion stories are told by means of computers, software, turntables, mixers, drum machines, and other digital technologies. As they tell their religious conversion stories, rappers and hip-hop artists are inaugurating new religious communicative practices.

Adam Banks, in his book Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age, argues that rappers and DJs should be regarded as modern poets (Banks calls them “griotic figures”), drawing upon a network of rhetorical practices and traditions in order to tell their stories. According to Banks, technology is central to hip-hop rhetorical practices: “Because technology use, production, and design … are all so thoroughly embedded in rhetorical acts, one could argue that technologies themselves are rhetorical in nature.” The technologies—turntables, mixers, and digital audio software—that enable a hip-hop artist to chop, scratch, or loop a beat are all rhetorical tools for storytelling. Since hip-hop artists rely so heavily on these technologies to tell their stories, it is impossible to comprehend hip hop without considering the tools of the craft.

It might be helpful here to note a distinction between the literary and artistic forms chosen to tell stories of conversion and the technologies employed to communicate them. Yet, I would argue that technology and form are distinct-yet-connected matters, and maybe especially in this case. It is important to note that hip hop uses both new technologies and new literary and artistic forms for telling conversion narratives. While this essay focuses primarily on the influence of technology on hip-hop conversion narratives, form is not entirely disconnected from the conversation. New technologies open up new possibilities for transforming literary and artistic forms.

In the fourth century, Augustine had a limited number of tools for communication at his disposal. As such, Augustine told his story of conversion, Confessions, by using the media that was readily available to him. In the twenty-first century, significantly more tools for communication are now available. The age of digital media has made it possible for recent converts to tell their stories as media bricoleurs: posting videos on YouTube, sharing snippets of thought on Twitter, uploading audio podcasts and interviews, composing textual reflections, and conversing with others in digital spaces. Hip-hop artists, as they deploy unique rhetorical, technological, and multimodal techniques for communication, are on the vanguard of telling religious conversion stories through this new media.

Victor Del Hierro, a digital rhetoric scholar, has argued that hip hop provides a place for marginalized individuals to tell their stories: “As a culture that is known for not only being an outlet for disenfranchised youth, but also a place to tell stories from marginalized perspectives, what has sustained the growth of Hip Hop is the way the practices central to Hip Hop are transferred and localized both within and across communities.” Hip hop provides a space and community for marginalized individuals to compose and perform their conversion stories. Composing a conversion story through the conventions of hip hop may be more accessible (and more meaningful) to some individuals than telling the same story through written communication.

Will these albums from Kanye or Flame displace Augustine’s Confessions? Probably not. Nevertheless, these hip-hop conversion stories ought to have a place within the discourse about religious conversion narratives. While it might be possible to argue over which works are qualitatively better or more theologically profound, it is clear that Kanye, Flame, and others, are telling their stories of religious conversion in new and creative ways—and folks are listening. ♦

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.

Featured image: "Kanye's Sunday Service at Coachella" painting by Junko Abe. Body images: Extra Nos album cover by Flame; “La Conversion de Saint Augustine (The Conversion of Saint Augustine)” (c. 1435) by Fra Angelico (c. 1395-1455), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.