In Defense of the Liberal in the Study of Religion

Editor's note: In observance of the holidays, Sightings will be off next week

Editor's note: In observance of the holidays, Sightings will be off next week. We wish to thank all those who have contributed, read, shared, and responded to our columns this past year. See you in 2017!

Editor's note: In observance of the holidays, Sightings will be off next week. We wish to thank all those who have contributed, read, shared, and responded to our columns this past year. See you in 2017!

In the aftermath of the U.S. presidential election and the political divisions it highlighted, I noticed that Nicholas Kristof’s May 7, 2016, New York Times column, “A Confession of Liberal Intolerance,” began trending online. In this piece, Kristof argues that American universities, especially in their humanities and social science departments, are problematically dominated by liberal faculty and ideas. Himself an avowed liberal, Kristof suggests that the American academy should actively work to include within it conservative thought and, in particular, evangelical Christian perspectives:

The stakes involve not just fairness to conservatives or evangelical Christians, not just whether progressives will be true to their own values, not just the benefits that come from diversity (and diversity of thought is arguably among the most important kinds), but also the quality of education itself. When perspectives are unrepresented in discussions, when some kinds of thinkers aren’t at the table, classrooms become echo chambers rather than sounding boards—and we all lose.

Kristof goes on to cite statistics reflecting the low proportion of Republicans represented in American university faculties as well as social scientific data and anecdotal evidence of bias against Republicans and evangelical Christians in university contexts. (Kristof subsequently defended his view against his critics in his May 28, 2016, column, “The Liberal Blind Spot.” On December 10, 2016, he updated—and largely restated—his argument in light of the Trump election; see “The Dangers of Echo Chambers on Campus” under Resources below.)

Though Kristof’s special concern is not the academic study of religion, consideration of it might yield fruitful insights regarding his claims and proposed remedies. In his diagnosis of liberal bias, Kristof focuses on non-sectarian higher education—primarily public universities and private, non-religious universities. I will thus focus my attention there, even as I acknowledge that there is a significant number of confessional colleges and universities that this focus ignores and that, if considered, might reorient the discussion, at least in part.

As the quote above exemplifies, Kristof frames his consideration of diversity in the academy in terms of perspectives and kinds of thinkers. In both cases, his interest is content—what is thought and whether it is identifiably liberal or conservative. The good that Kristof seeks is a diversity of perspectives.

What Kristof omits is any consideration of method or, even more importantly, methodology. In the study of religion, this distinction between claim and methodology is a vital one, especially as it relates to the value of diversity. As a critical biblical scholar, my methods and methodology are shaped by the Enlightenment principles of empiricism and rational thought. I thus reject claims that appeal to authority—human or divine—rather than empirical evidence and reason. Such perspectives are not valuable to my work because they are founded in a fundamentally different set of principles for inquiry and argumentation. Kristof’s torchbearers of conservatism, evangelical Christians, have oftentimes championed religious authority rather than empirical evidence to support their claims. In such cases, critical scholars reject their perspectives.

Curiously, Kristof acknowledges precisely this issue but rejects its cogency. He notes that, in a Facebook discussion he initiated on this topic, one respondent wrote, “Much of the ‘conservative’ worldview consists of ideas that are known empirically to be false.” Kristof characterizes this response as “scornful” and the conversation overall as one that “illuminated primarily liberal arrogance.”

Yet insistence upon a shared set of methods and methodology (which are themselves constantly being challenged and refined), such as in critical biblical studies or the academic study of religion more broadly, hardly limits a diversity of perspectives. It instead makes discussion possible, clarifying a baseline for valid argumentation while leaving ample room for marshaling and evaluating different evidence, a process that inevitably leads to conflicting claims. These features of scholarly discourse also underscore that, notwithstanding Kristof’s assertion, the academy does not value an unqualified diversity; indeed, it never has.

Finally, I would note that insistence upon critical methods and methodology—or what we might term more generally, with Michel Foucault, “the critical attitude”—does not necessarily exclude those who hold conservative or specifically evangelical Christian views. All comers, whatever their political or religious persuasion, may engage productively on such terms and should be welcome to do so. At the same time, some may choose not to engage, preferring, for example, creed over critical inquiry. The academy need not exhibit hostility toward such individuals, but neither must it include their perspectives in its discourse.

Resources

- Foucault, Michel. “What Is Critique?” In The Politics of Truth. Ed. Sylvère Lotringer. Trans. Lysa Hochroth and Catherine Porter. Semiotext(e), 2007.

- Kristof, Nicholas. “A Confession of Liberal Intolerance.” The New York Times. May 7, 2016.

- —. “The Dangers of Echo Chambers on Campus.” The New York Times. December 10, 2016.

- —. “The Liberal Blind Spot.” The New York Times. May 28, 2016.

- Stephens, Randall J., and Karl W. Giberson. The Anointed: Evangelical Truth in a Secular Age. Belknap, 2011.

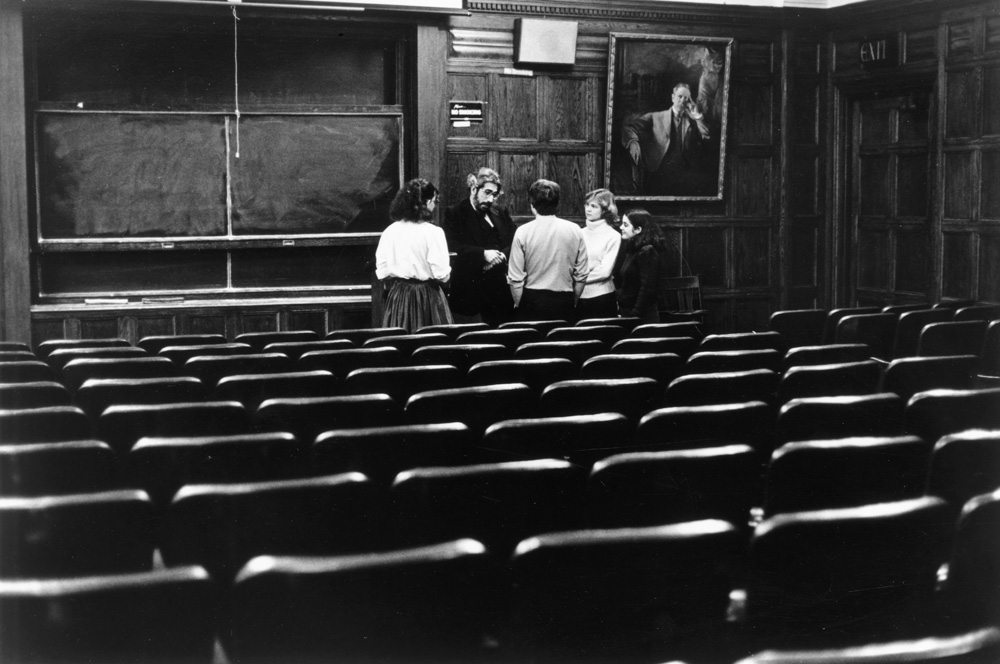

Image: Jonathan Z. Smith, the Robert O. Anderson Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the Humanities, pictured with a group of students. | Photo credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf1-07710], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Author, Jeffrey Stackert, is Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His most recent book, A Prophet Like Moses: Prophecy, Law, and Israelite Religion (Oxford University Press, 2014), analyzes the relationship between law and prophecy in the pentateuchal sources and the role of the Documentary Hypothesis for understanding Israelite religion. He is currently working on a monograph on the biblical Priestly religious imagination and is also coauthoring a commentary on the biblical book of Deuteronomy. Author, Jeffrey Stackert, is Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His most recent book, A Prophet Like Moses: Prophecy, Law, and Israelite Religion (Oxford University Press, 2014), analyzes the relationship between law and prophecy in the pentateuchal sources and the role of the Documentary Hypothesis for understanding Israelite religion. He is currently working on a monograph on the biblical Priestly religious imagination and is also coauthoring a commentary on the biblical book of Deuteronomy. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco, a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Click here to subscribe to Sightings as a twice-weekly email. You can also follow us on Twitter.