Connection and Celebration at the World's Parliament of Religions

At the height of racism in the US and Western colonialism, the Parliament was one attempt to mitigate human division and the sectarian passions nurtured and released by religious certainty.

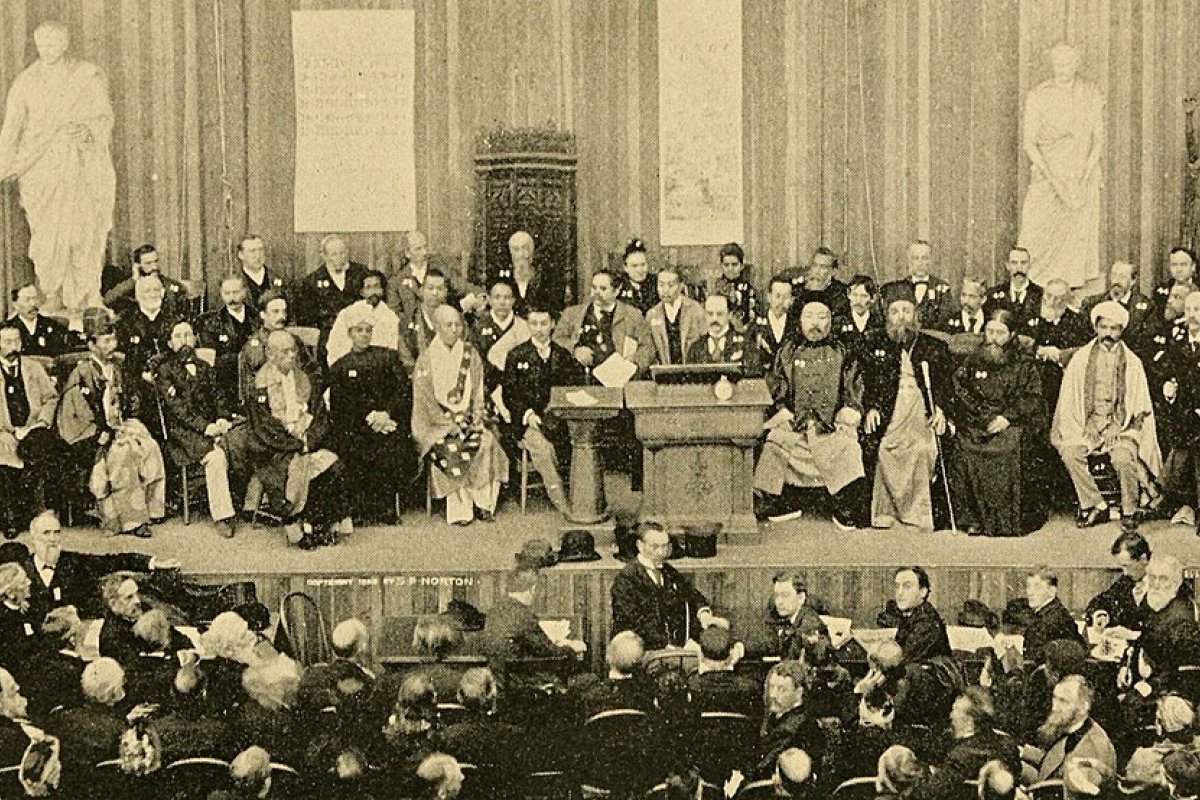

This summer, Chicago will host the Parliament of the World’s Religions. This will mark the 130th anniversary of the first World’s Parliament of Religions, which was also held in Chicago in 1893. The title of this year’s Parliament is, “A Call to Conscience: Defending Freedom and Human Rights.” The Parliament brings “together faith and religious leaders, academic and industry experts, and institutions and grassroots organizers committed to interfaith dialogue and action.” In an age of increasing ethno-racial appeals beyond national boundaries and with the rise of white supremacist violence in the US, it is helpful to revisit the original impetus of the first Parliament.

Much scholarship, including my Burden of Black Religion, has criticized the original Parliament for its Protestant supremacy, its exclusion of African American voices, and its negative and racist depictions of African peoples, among other things. Here, however, I highlight a more positive legacy of the Parliament by pointing to its enduring values of humility, respectful pluralism, and a theology of brotherhood1 that was bequeathed by the ecumenical tradition out of which the Parliament emerged.

Philip Schaff, a Protestant leader who had worked years for unification efforts within Christianity, argued that the Parliament would further his vision of Christian ecumenism based on “ethical unity” and “Christian freedom” by opposing a “spirit of pride, selfishness and narrowness.” Prince Serge Wolkonsky from Russia urged in his address, “Universal Brotherhood,” that attendees embrace an already existing human connection. He stated: “Human brotherhood is not a club where membership is needed to enjoy the privileges. Not by instituting societies or associations shall we inspire feelings of brotherhood, but in breaking the exclusiveness of those which exist.” Kaufman Kohler, a prominent leader of Reform Judaism, emphasized human unity, the divine image, and the “bonds of human brotherhood” in his talk. The repeated claims about the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of humanity have seldom been noted, but they are examples of multiple religious leaders (even beyond the Jewish and Christian traditions) who sought to expand the circle of human connection beyond blood ties, national boundaries, and even inherited religious traditions. At the height of racism in the US and Western colonialism, the Parliament was one attempt to mitigate human division and the sectarian passions nurtured and released by religious certainty.

Historians have produced a lot of scholarship on the negative implications of the Parliament, especially for the study of comparative religions. The Parliament's organizers were operating under the pervasive cultural assumption of Anglo-Saxon superiority and the higher achievements of American and European cultures over "primitive" peoples. Yet, two positive consequences of the Parliament are relevant to our current context: first, its nascent grasping for a robust form of religious pluralism, and second, its efforts to reduce religious conflict and hatred by emphasizing wider human connections even in the face of competing truth claims. Historian William Hutchison rightly notes that the Parliament was unprecedented in “promoting understanding and mutual respect among all the ‘great religions’” and just in bringing together Jews, Catholics, and Protestants in the US. Roughly two hundred representatives of a dozen religions were present. The emphasis on religious pluralism would lead in time to more respectful comparative studies of religions over time. Flowing from the ecumenical impulse was also an incipient theology of brotherhood that would flourish more fully by the 1920s and later in ecumenical organizations such as the Federal Council of Churches.

The theology of brotherhood followed from this more robust support for religious toleration and attempts at lessening sources of bitterness and division within Protestantism. The theology of brotherhood was a positive affirmation of the unity of humanity, the common bond of Christians in the church as the body of Christ, and the fatherhood of God as the basis for human kinship. This more capacious vision rejected invidious distinctions between the races, repudiated the hierarchical ordering of races, and rejected white supremacy and its purported grounding in a divine order. In practice, this theology urged Christian churches to fight against racial oppression within churches and in the broader society, to affirm their shared humanity and common link to Christ as head of the church, and to welcome people of other races into their inner circles. Specifically, it meant the rejection of segregation; affirmation of the dignity of the human person regardless of race, ethnicity, or national origin; the right to vote for black Americans; and the removal of discrimination from all aspects of American society. The ecumenical impulse at its best did not deny or trivialize real cultural, political, and social differences, but it sought to render human diversity and religious pluralism as potential sources of strength and creativity rather than as forces to be tamed or controlled.

In reflecting on the consequences of these ecumenical efforts, historian David Mislin argued that “one legacy that remained was the sense that America’s religious communities had more that united them than separated them.” The embrace of uncertainty and doubt by that generation of liberal Protestants and an ensuing emphasis on humility and limitations are some of the more enduring features of the ecumenical tradition that gave rise to the Parliament. Perhaps it was that spirit that inspired Reinhold Niebuhr’s prayer that we be permitted to “survey the ages in our brief hour, and to claim our kinship with the noble living and the noble dead, to find our place in the long sad and majestic history of our race and to see our duties and responsibilities in ever-widening circles of human relations.” The Parliament was a very real and earnest attempt to come to terms with and celebrate distinct religious traditions while lauding our deeper human connections. That legacy is all the more important and urgently needed in our current context of racial and religious violence.

Image: World's first Parliament of Religions, held in Chicago in connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Image from public domain, via Princeton Theological Seminary Library.

--

1 There are legitimate concerns about the gendered nature of "brotherhood" and "fatherhood," since these are male terms and they may sound exclusionary to women. As I discuss in greater length in my forthcoming book A Theology of Brotherhood, historically these expressions and their intended meaning included men and women, and I cannot really find a replacement for them. They expressed a more capacious notion of human connection and kinship. But to find a substitute term that is acceptable to modern sensibilities would be anachronistic and problematic in its own ways.