Common Sense and the 2020 Election

How do screens change our sense of national community?

Stumps and porches were once the tools of presidential campaigns. Candidates traveled by rail, stood on stumps, spoke to crowds, and even rolled a giant paper ball from town to town. Or, in the case of James Garfield, tree stumps were swapped for front porches; Garfield’s presidential campaign relied on crowds of people traveling by rail to his house in Ohio to hear him speak from his own front porch.

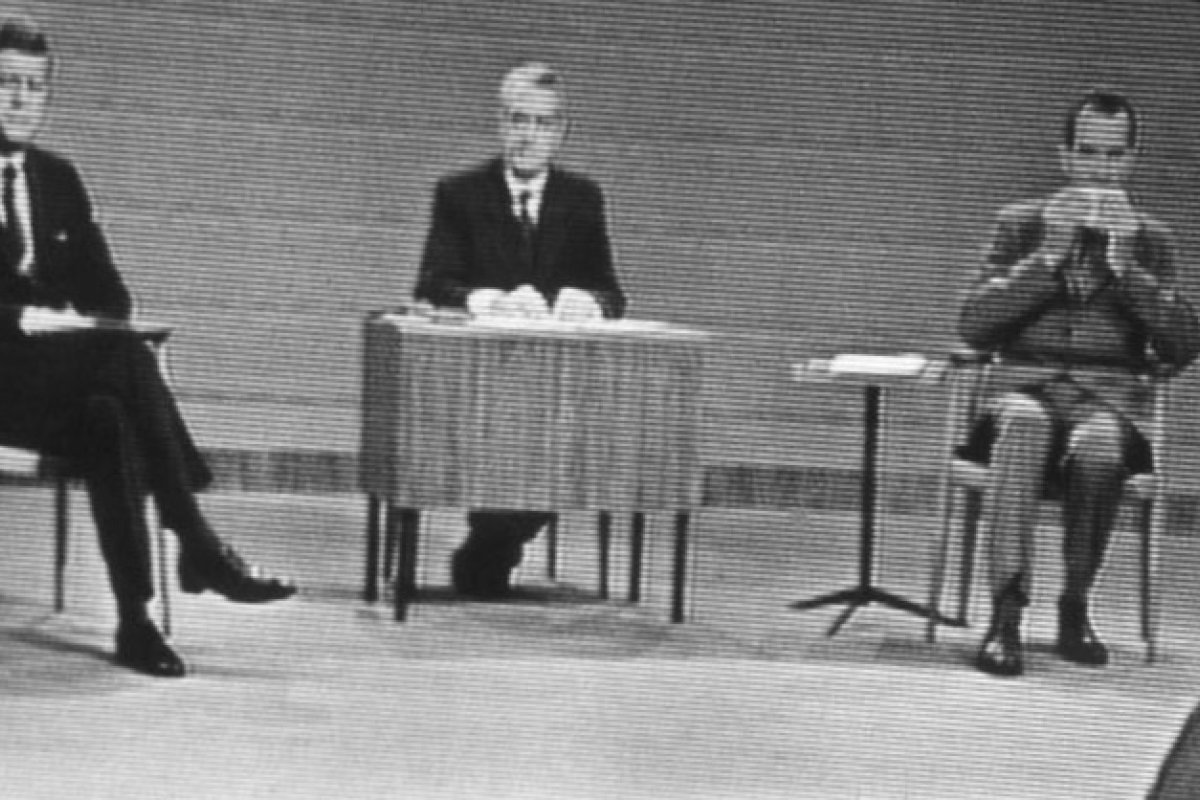

For the past sixty years, screens have supplanted stumps and front porches. Beginning with the Kennedy-Nixon debates in 1960, stumped voters could sit on their own front porches and watch the presidential debates. And while subsequent presidential campaigns have still given priority to in-person appearances, the coronavirus pandemic has forced the 2020 election to be even more heavily mediated by electronic media through television and computer screens as the only safe means of political engagement.

The 2020 Presidential debates are an example of this phenomenon. The first debate, which took place on September 29 at Case Western Reserve University, included an inconsequentially small onsite audience. The rest of the world was forced to view the debate as a visual product through a screen. In the absence of a physically present audience – the kind of audience that Walter Ong described as, “acting here and now on one another and on the speaker”[1] – the candidates largely fixated on one another.

This election year—more than any other in American history—is lacking in both common sense and communion. Among several other important factors, electronic screens are playing a large part in eroding our sense of ourselves as a national community this election year. While socially distancing is of course a necessary safety measure in the midst of a pandemic, and while it is only one aspect of a much larger issue, this technology-induced disintegration is ripe for religious reflection.

The ancient notion of sensus communis, from which the term common sense derives, has to do with the unity of the bodily senses. Discussions about the bodily senses appear in Plato’s Theaetetus, in which Socrates declares, “The senses are variously named hearing, seeing, smelling; there is the sense of heat, cold, pleasure, pain, desire, fear, and many more which have names, as well as innumerable others which are without them.”[2] Aristotle, in De Anima, further explored the bodily senses, proposing an integrated perception of the physical world known as koiné aesthesis, or common sense.

While various scholars have disagreed on the nuances of sensus communis, there is widespread agreement that the sense-organs are vital instruments for apprehending and interpreting the external world. The communion of the bodily senses – touch, sight, hearing, smell, so forth – are integral for knowledge and perception.

The media theorist Marshall McLuhan can help us understand why this election year is particularly lacking in common sense. McLuhan argued that bodily senses are reoriented by media. Various forms of media prioritize one bodily sense over the other and result in a disintegration of the senses; watching television gives priority to sight over other bodily senses. According to McLuhan, “The extension of any one sense alters the way we think and act – the way we perceive the world.”[3]

Losing all sensible bodily presence and passively receiving a candidate’s face and voice through a screen alters our perceptions. Sights and sounds, not flesh-and-blood embodiment, reign supreme. This makes it difficult to recognize the embodied concerns of others. With our radically altered sensibilities, flesh-and-blood encounters with our fellow citizens take on a new shape; what we have already seen and heard through screens overrides our perception of the embodied neighbor that is our fellow citizen.

This election year, with its sparsely filled debate halls and omnipresent visual products, is prioritizing some of our senses over others. What happens when we can only see candidates on a screen? Who controls what we see and hear? What are we not seeing or hearing? The mediation of the screen – and the people who manufacture the image it broadcasts – give us a disintegrated sense of each of the candidates.

And it is not only the candidates who are ideologically and physically screened off from one another; citizens are, too. Koinonia, the religiously rich notion of fellowship, communion, and impartation, is lost without a common sense. Sharing together in conversation, taking part in discussion, and participating in democracy is especially difficult to do exclusively through screens. In the broad sense of the term, it is difficult to commune with candidates and fellow-citizens by way of screens.

Certainly, these issues have been a problem at least since the televised Kennedy-Nixon debates of 1960. However, the 2020 presidential debates are adding greater exigency to these issues. Maintaining common sense and communion when it comes to candidates and fellow citizens is a formidable challenge this election year. How does one go about fostering any degree of common sense and communion in this digital age?

The words of Martin Luther in the Small Catechism are surprisingly applicable here. In his explanation of the first article of the Apostles’ Creed, Luther declares, “I believe that God has made me and all creatures; that He has given me my body and soul, eyes, ears, and all my members, my reason and all my senses, and still takes care of them.”

As we engage the presidential debates in these coming weeks, Luther’s words remind us to consider which of our senses are being engaged and which of our senses are being neglected. Being an informed voter requires us to remember that there is a living, breathing human being behind every comment on social media. We are indeed more than just our eyes and ears; religion reminds us to interrogate what it means to be wholly human creatures with the ongoing communion of body and soul, eyes, ears, members, reason and senses.

[1] Walter J. Ong, S.J., “The Writer’s Audience is Always a Fiction” (PMLA 90 [1975]: 9-21), p.11.

[2] 156b, trans. Benjamin Jowett.

[3] McLuhan, Marshall, The Medium is the Massage (New York: Random House, 1967), p.41.

Image: The 1960 Nixon-Kennedy debate, the first presidential debate to be televised (courtesy of Granger Academic).

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.