Bad Faith History: The End of Roe v. Wade and The Supreme Court’s Myth about Abortion in the United States

The world that the Court’s opinion imagines is intimately (and frighteningly) consonant with a white, Christian nationalist vision of our nation.

Last week, The United States Supreme Court ruled in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, upholding the state of Mississippi’s recent ban on abortions performed after a fetal age of fifteen weeks. The court’s ruling reversed Roe v. Wade, the nearly fifty-year-old precedent that made access to an abortion a constitutional right. Writing for the majority opinion, Justice Samuel Alito rejected federal protections for abortion on the basis that “the right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and tradition.” Throughout the opinion and the draft that was leaked last month, Alito makes frequent recourse to “history” as a significant factor in the Court’s decision-making and as a justification for its conclusions.

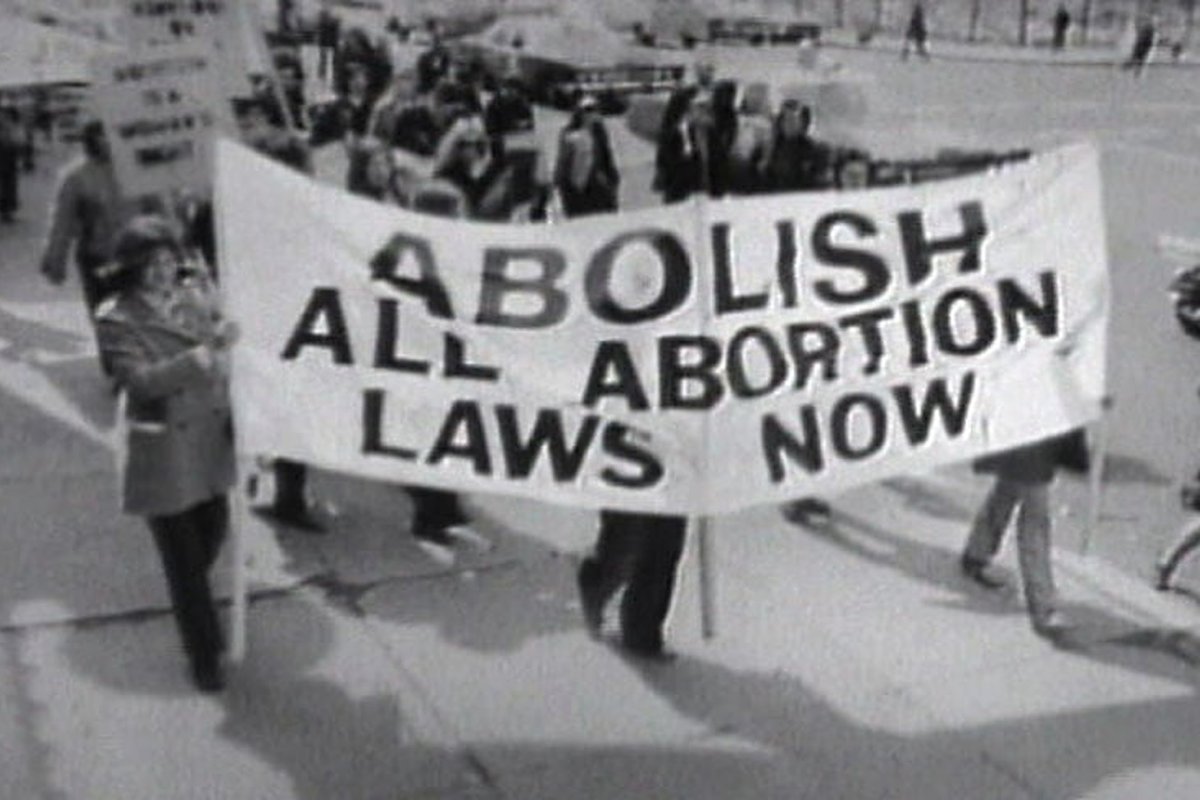

In the days surrounding the ruling, countless responses have offered incisive critiques of the Court’s inaccurate history of abortion in American life. For instance, some have shown that until the mid-nineteenth century most states and their citizens understood abortion to be both morally and legally acceptable until the point of “quickening,” the stage when the pregnant person is able to discern fetal movement (typically well into the second trimester). They have argued that practice on the ground did not always adhere to legal prohibitions on the books; people did perform and receive abortions even when and where they were criminalized. Still others have undermined the assertion that ending a pregnancy has historically been a “critical moral question” or religious issue in the United States by showing that this perspective actually emerged from a coalition of conservative politicians and Christian groups formed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Numerous other criticisms have been leveled at the opinion’s use of history—that it is idiosyncratic and contradictory; that it excludes oral (and therefore non-majority) histories; that it relies too heavily on the ideas of Sir Matthew Hale, a seventeenth-century jurist whose claim to fame is the denial of marital rape and a letter of over two hundred pages in which he mansplains to his granddaughters.

These and other interventions present a formidable critique of the Court’s “bad history” of abortion in the United States. Still, we gain a fuller picture of the motivations and consequences of the Court’s ruling if we consider it through not only the lens of history but also of myth. As Bruce Lincoln has argued, myths are “ideology in narrative form.” That is, myths are stories that people, especially those in power, produce and reproduce in order to reflect and legitimize their values and prerogatives. Myths are cast by their tellers as history—an ostensibly neutral account of the past—when they are actually about the present moments in which they are created and re-told. They are cast as stories produced, authorized by, or anchored in a force greater than humanity—God, the gods, the sacred, tradition—when they are actually created and preserved by and for human beings for their own ends.

The Dobbs opinion is not simply bad history; it is bad faith history, because it is not actually an attempt at history at all. The story it tells of the American relationship to abortion is not an accurate account of the past but rather a partisan narrative presented as an accurate account in order to suit the ideological agenda of the nation’s political and religious conservatives. It projects into the American past a perspective on abortion that reflects the priorities of the twenty-first-century religious right. “This is how we used to be—a nation of moral, upstanding people,” the Court’s opinion implies. “This is who we once were and should be again. We’ve never really been a nation that approved of abortion. It has never really been deeply rooted in our history. And so we must return to this better, purer way of being.” In other words, “We must once again be who we never were.”

Reading the Court’s opinion through the lens of myth offers critics a necessary tool to understand (and therefore challenge) its decision. Without this conceptual work, we risk missing the ways that Dobbs and the fall of Roe v. Wade are connected in both method and nature to other recent Supreme Court rulings about the establishment of religion, the rights of incarcerated people, the racist gerrymandering of voting districts, and the degradation of the environment, to name but a few. We miss the ways that the Court’s language, while not explicitly what we might call “religious,” connects to and supports white, Christian nationalist claims about who we should be as a country. We do dissent a disservice when we argue only or primarily at the level of historical nuance because the Court’s majority and far right politicians (including but not limited to former president Donald Trump) are not interested in historical accuracy. They are interested in ideological fidelity. It matters less that the stories they tell reflect actual events that occurred in the past than that they reflect—and at the same time, obscure—the goals and interests of a particular, powerful set of politically and socially conservative Americans.

The stories we tell about ourselves (and, perhaps more importantly, the stories we are told about ourselves) shape the ways we are able to imagine and make the world—what we think is possible, what we hope for, what we are willing to accept or take from others. The world that the Court’s opinion imagines is intimately (and frighteningly) consonant with a white, Christian nationalist vision of our nation. In this vision, gender is binary and complementary, women’s reproductive labor is a natural and moral obligation (I write “women” because such a vision expressly denies the possibility of pregnant people who are not women), and pregnancy is something that happens to a person, to a body, regardless of consent. The violation of the bodily autonomy and human rights of pregnant people presages the destruction of countless other hard-won rights that make possible the safety, security, and flourishing of American citizens.

The Court’s invocation of “history” is not surprising. It is what people with power do in order to sustain the conditions required to ensure the continuation of that power. It is what communities—religious, legal, political, social, or otherwise—have likely always done and will continue to do. But for scholars of religion, who are ostensibly trained to find the patterns and problems in the use of mythic narratives, accepting such stories at face value would be a failure of professional responsibility. It is not enough to prove that the religious right gets the details wrong; we must do more, in every venue and on every register, at the general and the specific, without fail and without doubt. Otherwise we risk laboring in the dark.