Andy Warhol’s Iconicity

Exploring the religious dimensions of the exhibit, "Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again," currently on display at the Art Institute of Chicago

“From A to B and Back Again,” the superbly curated retrospective of the artistic career of Andy Warhol from the Whitney Museum currently on display at the Art Institute of Chicago, is mapped out to be a pilgrimage. Over 400 items displayed in multiple, intersecting rooms dictate a pace that commences with giddy anticipation and easy recognition, then gradually but inexorably slows to considered (and reconsidered) contemplation. The cumulative experience is at once exhausting and exhilarating.

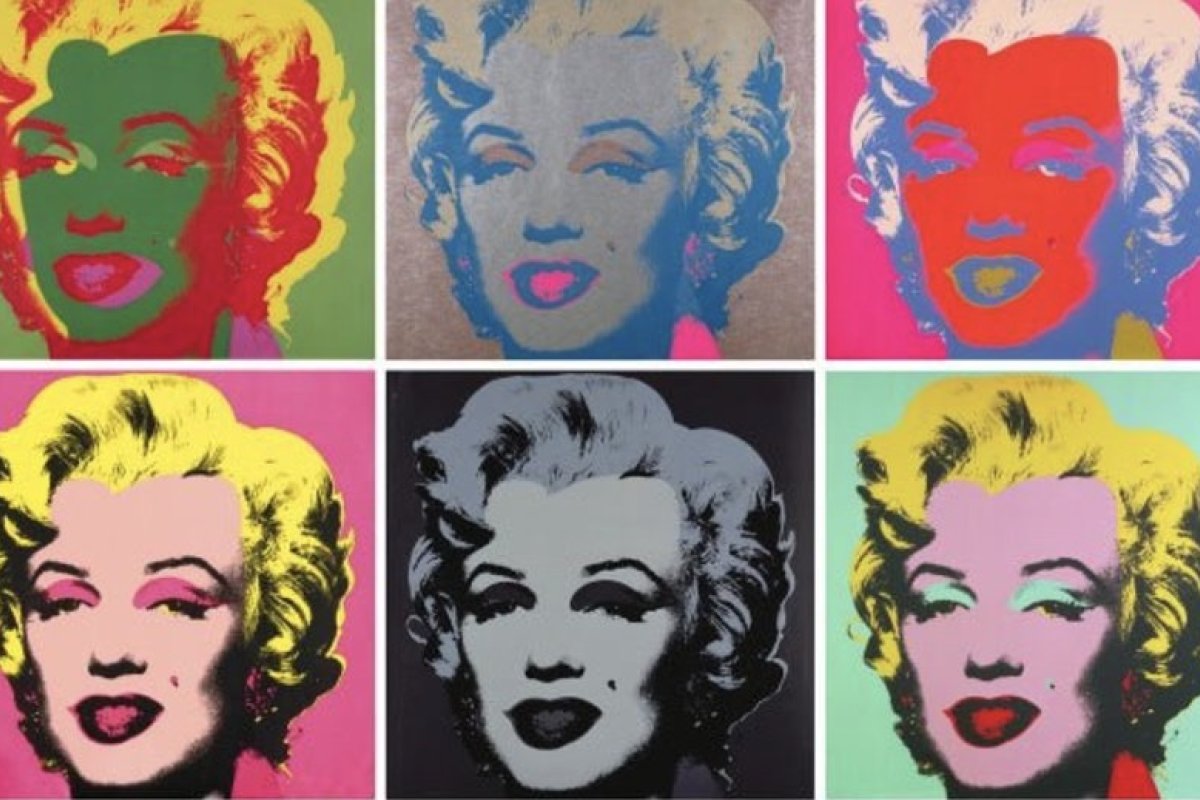

This is perhaps counterintuitive to many, for whom the experience of Warhol’s art presciently anticipates our experience in the world of digital imagery: the ease of reference, the quick glance, the pithy comment, all couched in anticipation of what will come next. Warhol may not have envisioned the cell phone, but he certainly recognized, explored, and exploited the human propensity for a certain kind of iconicity that was at once knowing and fleeting. And Warhol linked this propensity to the twin American icons of capitalism and celebrity: the Coke cans, the silkscreens of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, are all emblematic of “fifteen minutes of fame.”

The exhibit makes the powerful case that this understanding of Warhol is reductive, at least to the degree that it renders Warhol either its unreflective pawn or, perhaps more tellingly, its ready and willing participant. Taking into view his remarkable range of work across a sequence of rooms arranged by angles and half walls that serve at once to foreshadow what would come, and to keep the viewer mindful of what had been done, underscores and nuances Warhol’s intent (and his intensity). Inserted almost (but not quite) unobtrusively into the transitional corners and apertures throughout the exhibit are works that conform to its chronological arrangement but that Warhol never displayed—most memorably an ongoing series of exquisite, intimate, line drawings of the hands and feet of friends and lovers.

This arrangement leads the viewer to consider the unmistakable but not necessarily intuitive connections between Warhol’s early, unsigned work in advertising, his signature presence as self-promoting avatar of American pop in the 1960s, and the elegiac and culminating final expression of a life of boundless artistic productivity.

The first two stages of Warhol’s career—in advertising and in pop—reflect keenly honed talent and tenacious integrity. Viewed in the aggregate, the Coke cans and the celebrities and everything else prove unsettling: they examine us as much as we examine them. The subsequent turn to Warhol’s third stage serves not just to reinforce that experience but ups the ante. The exhibit informs us—too briefly, at least from the perspective of the scholar of religion—that Warhol was a Byzantine-rite Catholic who attended daily Mass but chose to keep his religion (like his sexuality) as far removed as possible from public display.

The final stage includes striking work about endings. Three works especially underscore this effect, while unmistakably deploying Warhol’s signature methods. We are presented with “The Last Supper,” one of approximately one hundred silkscreens and drawings of Da Vinci’s masterpiece that Warhol executed on commission for an exhibition in Italy. Fashioned from an encyclopedia photograph of the painting, Warhol has superimposed upon it a patina of battle fatigue material, through which we glimpse the recognizable iconography of da Vinci’s painting studded with the now-familiar advertising imagery. The discordant mix of broadly familiar with specified particularity in this wide, rectangular format obliquely but unmistakably invokes the Byzantine iconostasis, the altarpiece in Orthodox churches that juxtaposes images telling the story of sacred history with those of local piety. Warhol’s own brew of classic religious scene, advertising logos, and religious convention in this “The Last Supper” together forge, the longer one gazes, a meditation on the impending oddity of the locution, a “Christian America.”

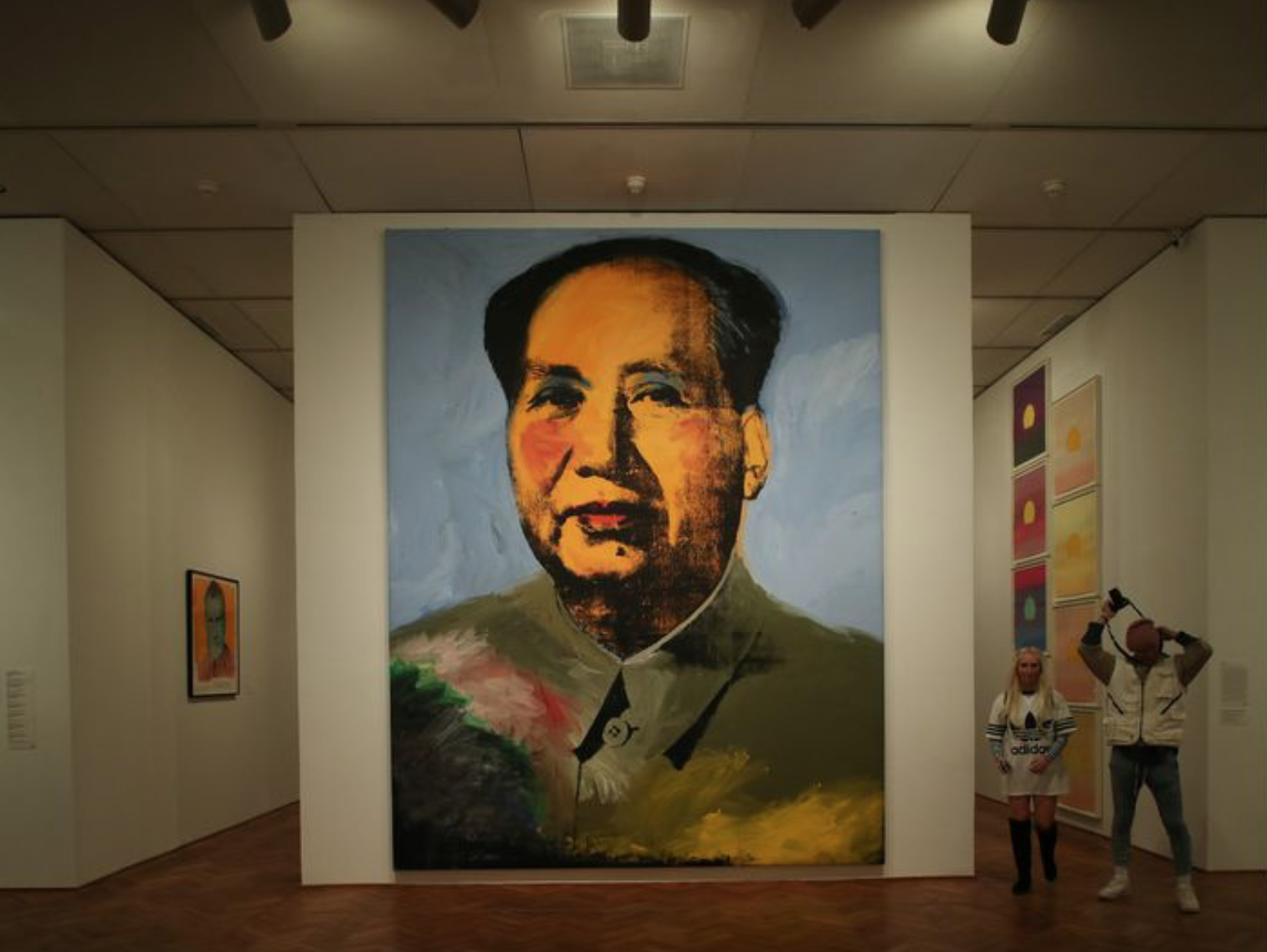

Looming over the exhibit is its largest image, Warhol’s late portrait of Mao Tse-Tung. Here he takes his signature silkscreen medium global. A metonymy for China, Mao is literally enlarged to personify the celebrity of charismatic power. Charisma and celebrity are seen to be continual at the same time that they are now continually ironized. By striking contrast, one of the more understated images on display is a set of nine photographs of one of Warhol’s pet subjects, Jacqueline Kennedy, taken at three moments on November 22, 1963: iterations of the iconic First Lady in moments of celebratory acknowledgment of the crowd from the motorcade, of horrified recognition, and of inconsolable grief.

The title of the exhibit—“From A to B and Back Again”—is taken from Warhol himself, who claimed the phrase encapsulated his aesthetic. Crafted like his art to be disarmingly straightforward, it is anything but that. For viewers, it immediately displaces the much more widely cited “fifteen minutes of fame” as the appropriate coda for Warhol.

Invoking the thematic of pilgrimage, “From A to B and Back Again” is at once direct, simple, and recursive. Here direct and simple bespeaks the way that images become iconic, and Warhol’s enduring cognizance that, as an American artist, that process of becoming is aesthetically interesting yet readily available to the blandishments of commercialism and celebrity. That may be what Warhol meant by “From A to B.” Aesthetic practice, at least in America, cannot avoid these. To pretend otherwise is artistic hypocrisy.

Then there is “And Back Again.” The viewer concludes the pilgrimage recognizing that this aspect of Warhol is easy to underestimate, even to ignore: his repetition is innately religious, and partakes of ritual’s insistence that we remember what we would otherwise readily overlook or even forget. Warhol unmasks our willingness to ignore the depth of the icon—its capacity for social comment, and for grappling with the decisive fact of human finitude.

This strikes me as consonant with Warhol’s emergent aesthetic, but it risks eliding a signpost of his art’s protean, repetitive, secondhand nature: it is constantly on guard against self-assured commentary. Image takes us to icon, but it also takes us “back again.” What to say in front of art that speaks at once so eloquently yet also so ambivalently? “From A to B and Back Again” underscores Warhol’s mordant sense of the relation of finality to fixed meaning. ♦

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.

Images: Feature image: Andy Warhol, "Marilyn Monroe," 1967, screenprint. Body images: An installation shot of "Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again" at the Art Institute of Chicago (Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago); Warhol's "Mao" is displayed as part of "Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again" at the Art Institute of Chicago. (Photo: John J. Kim)