The Acquittal of "Patient Zero"

In the midst of the tumultuous vitriol of the recent election and its aftermath, it was unfortunate that a significant story regarding a once virulent legend of the AIDS epidemic went relatively unnoticed—a story that returns us to the apogee of the AIDS crisis in the United States.A new study, bolstered by the genetic analysis of thousands of 1970s blood samples, has acquitted Gaëtan Dugas, the gay French Canadian flight attendant once erroneously identified as “Patient Zero” for the transmission of HIV in the U.S., and charged with having personally transmitted HIV to hundreds, even thousands, of American men before his death in 1984

In the midst of the tumultuous vitriol of the recent election and its aftermath, it was unfortunate that a significant story regarding a once virulent legend of the AIDS epidemic went relatively unnoticed—a story that returns us to the apogee of the AIDS crisis in the United States.

In the midst of the tumultuous vitriol of the recent election and its aftermath, it was unfortunate that a significant story regarding a once virulent legend of the AIDS epidemic went relatively unnoticed—a story that returns us to the apogee of the AIDS crisis in the United States.

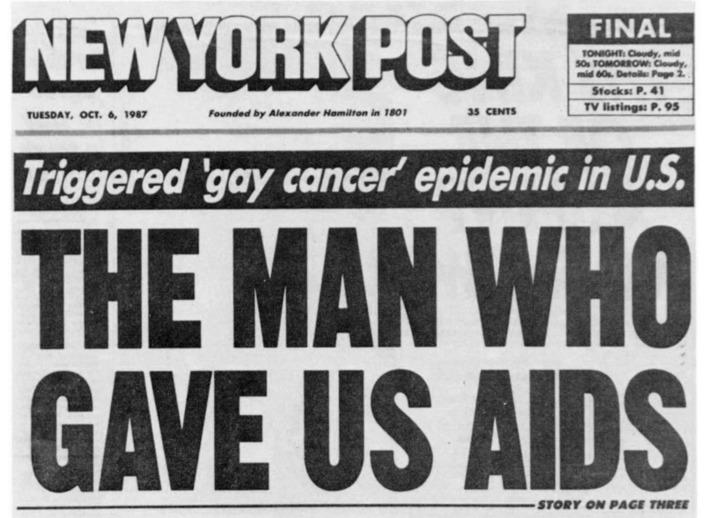

A new study, bolstered by the genetic analysis of thousands of 1970s blood samples, has acquitted Gaëtan Dugas, the gay French Canadian flight attendant once erroneously identified as “Patient Zero” for the transmission of HIV in the U.S., and charged with having personally transmitted HIV to hundreds, even thousands, of American men before his death in 1984. Dugas once proved such a seductive scapegoat that the New York Post even labeled him in a headline as “The Man Who Gave Us AIDS,” while Time magazine followed with a story called “The Appalling Saga of Patient Zero.” But now the new study, published in the journal Nature, demonstrates that Dugas’s blood, sampled in 1983, possessed a viral strain already present in New York years before Dugas started to frequent gay bars in the city in 1974. Without question, there is no way that Dugas could have been “Patient Zero.”

The saga of the slander against Dugas largely began with the 1987 book And the Band Played On, written by Randy Shilts, an investigative reporter in San Francisco. The book examined why AIDS was permitted to spread unchecked in the early 1980s, and in the midst of his research at the Centers for Disease Control Shilts stumbled upon a certain “Patient O,” originally identified as such to designate “outside California.” But somewhere along the way someone at the CDC confused the “O” for a zero and began to refer to this figure mistakenly as “Patient Zero”—a designation that Shilts (and the media) found all too attractive. The patient was, of course, Gaëtan Dugas. Shilts further villainized Dugas as a deliberate, even sociopathic, spreader of the disease who cold-bloodedly ignored a doctor’s demand to desist from having unprotected sex. Dugas was soon unwittingly cemented in public consciousness as the face of, and scapegoat for, a horrific new epidemic.

Dugas’s misidentification occurred at an unfortunate moment, when the American public was desperately in search of such a scapegoat. As historian Phil Tiemeyer remarks: “This character, Gaetan Dugas, has every trait of a villain that America is looking for in the AIDS crisis. He’s gay and unashamed about it. He’s beautiful. He’s even a foreigner who speaks with this seductive accent. He’s the perfect villain.” On the one hand, Dugas was ensnared by the Scylla of homophobia, especially the anti-gay vitriol of Jerry Falwell and President Reagan’s speechwriter Pat Buchanan, both of whom considered AIDS a just punishment for the “sin” of homosexuality. On the other hand, Dugas was simultaneously engulfed in the Charybdis of xenophobia, as a non-American introducing AIDS into the country found a fitting echo in the Cold War rhetoric of the “virus” of communism.

While the public’s uncertainty and anxiety about AIDS had many troubling consequences—notably the barring of 14-year-old Ryan White, a hemophiliac who contracted AIDS by a blood transfusion, from attending public school—the disease was stigmatized early on as the consequence of a “homosexual lifestyle.” In fact, the early view of the disease as a “gay problem” has often been cited as the reason why the disease was virtually ignored in policy and politics for so long. The unfortunate intertwining of religion, homophobia, and politics arguably hampered the initial response to the AIDS epidemic by the Reagan administration. Such dysfunction was especially evident in the internal strife between the administration and Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, as well as in the ineffectual Presidential Advisory Commission on HIV/AIDS, frequently criticized as being too conservative and light on expertise.

But the dangerous specter of stigma has far-reaching consequences—particularly when that stigma has originated in the alchemical combination of religion and fear over a mysterious new epidemic. Only in 2009 was the Obama administration finally able to overturn an immigration and travel ban against people with HIV. In fact, no major international AIDS conference had been held in the U.S. since 1993 because HIV-positive activists and researchers could not enter the country. Now, like that ban, the myth of “Patient Zero” has finally been put to rest. One hopes that humanizing Gaëtan Dugas will help further de-stigmatize HIV/AIDS.

Although, with the pending confirmation of Jeff Sessions—whose religious convictions have made his position on HIV/AIDS, not to mention contraception and LGBT rights, complicated at best—as U.S. Attorney General, it remains to be seen whether religion, homophobia, and politics will once again become toxically entangled.

Resources

- Doucleff, Michaeleen. “Researchers Clear ‘Patient Zero’ From AIDS Origin Story.” NPR. October 26, 2016.

- McNeil, Jr., Donald G. “H.I.V. Arrived in the U.S. Long Before ‘Patient Zero’,” The New York Times, October 26, 2016.

- Petro, Anthony M. After the Wrath of God: AIDS, Sexuality and American Religion, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

- Worobey, Michael, et al. “1970s and ‘Patient 0’ HIV-1 genomes illuminate early HIV/AIDS history in North America,” Nature, 539 (October 2016): 98-101.

Image: Front page headline from the Tuesday, October 6th, 1987, issue of the New York Post

Author, Mark Lambert, is a PhD student in Theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School. He previously completed a BA at Truman State University (2010) and an MA at the University of Chicago (2013). His scholarship focuses on the theological ambiguities of medieval attitudes about leprosy in an effort to understand the stigmatization of illness, whether Hansen’s Disease, HIV/AIDS, or mental illness. Author, Mark Lambert, is a PhD student in Theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School. He previously completed a BA at Truman State University (2010) and an MA at the University of Chicago (2013). His scholarship focuses on the theological ambiguities of medieval attitudes about leprosy in an effort to understand the stigmatization of illness, whether Hansen’s Disease, HIV/AIDS, or mental illness. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco, a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Click here to subscribe to Sightings as a twice-weekly email. You can also follow us on Twitter.