On Academic Time

Addressing new students at the Divinity School during orientation this year, Dean David Nirenberg talked about the university as a place in which it is possible, even necessary, to live in a different kind of time

Addressing new students at the Divinity School during orientation this year, Dean David Nirenberg talked about the university as a place in which it is possible, even necessary, to live in a different kind of time. Academe is fueled by the exploration of questions the answers to which may take months or years to develop, or might never be found at all. The moments spent in such a community as a student are therefore a precious gift.

Addressing new students at the Divinity School during orientation this year, Dean David Nirenberg talked about the university as a place in which it is possible, even necessary, to live in a different kind of time. Academe is fueled by the exploration of questions the answers to which may take months or years to develop, or might never be found at all. The moments spent in such a community as a student are therefore a precious gift.

Similarly, in his own address to our entering students, Professor Paul Mendes-Flohr reflected on the pride of a scholar in his footnotes, the fruits of long and sustained intellectual labor. Exhorting the incoming class to appreciate the weighty and serious work of the scholar, Mendes-Flohr cited Nietzsche’s The Dawn of Day, in which he defines scholarship as “that venerable art which exacts from its followers one thing above all—to step to one side, to leave themselves spare moments, to grow silent, to become slow—the leisurely art of the goldsmith applied to language: an art which must be carried out slowly, fine work, and attains nothing if not in lento.”

Both Nirenberg and Mendes-Flohr called on our new students to appreciate, savor, and serve as custodians of this culture of slow, methodical, accretive work. And both positioned that culture as standing in some fundamental ways over and against the “real world” in which we live, a world Mendes-Flohr characterized as typified by “fast food, high-speed internet connections, FedEx, and super-fast bullet trains.“

Of course, this conception of the research university—both in what it is imagined to be, and in how that idea stands in relation to a conception of the world outside the university—is nothing so new. Powerful social currents have been speeding up, becoming smaller, and chafing at the venerable, the old, and the slow since John Henry, Anna Karenina, Gutenberg, and even further, and university cultures have often resisted such pressures. But, as Nirenberg reflected, the pace of change itself today is becoming palpably faster. It feels harder and harder to keep up. The image of slow, methodical scholarship—spending an entire twenty-week semester on the first three pages of the preface to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, as Mendes-Flohr recounted from his first semester as a graduate student—seems downright quaint.

The stark relief in which “academic time” stands was made all the more evident by current events. At precisely the same time as these remarks were being given, Senator Jeff Flake was in the midst of trying to slow down a seemingly inexorable process, by first voting to confirm Judge Brett Kavanaugh and then, after what the New York Times reported as a breathless series of events, dramatically demanding a pause in order for the FBI to investigate allegations of sexual misconduct against the Supreme Court nominee. And this, of course, came on the heels of a memorable day in the life of the country, when questions of time and memory—of the relationship of past, present, and future; of sin, truth, justice, and forgiveness—were brought into a dramatic, painful, shattering focus.

For me, all of this also came amid the fall Jewish holidays, a time during which I and many others have lived in two calendrical registers: going to work for a few days, doing our shopping, taking care of business, and then taking off two days for Rosh Hashanah, a day for Yom Kippur, two days for Sukkot, and two more for Shemini Atzeret (the Eighth Day of Assembly). Since all of these days fell on weekdays this year, we can also add the regular weekly cycle of Shabbat to the count. Thus in the month of September fully twelve out of thirty days have been ones in which many American Jews were off email and social media, attuned to a different rhythm. While the fall holidays generate this sense of discontinuity with the general culture every year—how could they fail to do so?—in this year the sense of a split-screen life felt even more pronounced than usual. And yet, despite the hustle and bustle and stress living in these two time worlds can generate, the quiet I find is, in my view, a cousin to academic time.

In her closing reflection at our welcome ceremony, my colleague Cynthia Lindner invited those assembled to take one last sip of the cup of quiet and slowness that, even within academic time, is unusually present at that kind of communal gathering. Clearly our bodies and souls need it. But, the world seems determined to remind us, our individual and collective minds need it too.

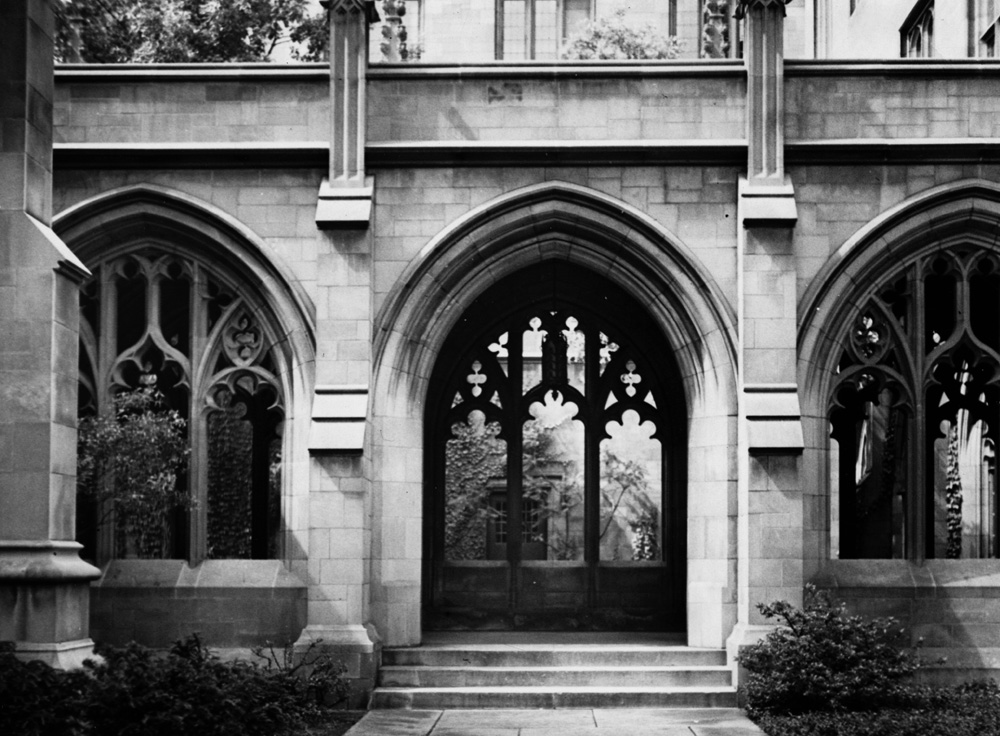

Image: Swift Hall, cloister, pictured in 1937 | Credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf2-08053, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Joshua Feigelson is Dean of Students at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

Joshua Feigelson is Dean of Students at the University of Chicago Divinity School.