The 1776 Report: Mind the (Religion) Gap

The revealing omissions in Trump's revisionist history of American Christianity

On January 18, 2021, two days before the end of Donald Trump’s presidency, his administration published its “1776 Report” to the White House website. (It was promptly removed at noon on January 20.) Trump described the Report as a “historic and scholarly step to restore understanding of the greatness of the American founding.” As others have noted, the Report is neither “historic” (it likely won’t be widely adopted) nor “scholarly” (the commission included no trained American historians). However, while many have dismissed the 1776 Report as a poor attempt to counter the 1619 Project or laughed it off as a lost-cause initiative of the Trump presidency, paying attention to its treatment of religion, and especially Christianity, reveals it to be a troubling, and even potentially dangerous, document.

One of the never-ending tasks for those of us who study American religious history is trying to correct what has been described as the “everywhere and nowhere” problem of religion in the narration of American history—that is, accounting for how religion is everywhere in American history but seemingly nowhere in American historiography. Jon Butler playfully described this problem as “jack-in-the-box faith,” wherein religion appears only episodically, popping up “colorfully” here and there and then disappearing: “momentary, idiosyncratic thrustings up of impulses from a more distant American past or ... foils for a more persistent secular history.” I’ve found Butler’s “jack-in-the-box” approach—paying attention to the ways religion is both invoked and omitted in rehearsals of American history—to be a helpful rubric for evaluating various attempts to re-narrate American history toward particular political ends, whether religiously motivated or not.

So where does religion pop up and disappear in the 1776 Report?

If one looked only to the main body of the Report, religion is treated in a surprisingly pluralistic manner, one of a variety of identities in a “melting pot” depiction of the United States. In relation to the Constitution, the ideal of “religious liberty” is repeatedly stressed, and there is even a statement about how divisions in Christianity posed a challenge to achieving political unity in the young republic. Then, the report cites “The Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” to rebut John C. Calhoun’s proslavery argument (p.12). All in all, religion is pretty much absent in the body of the Report, and the coverage it does receive is relatively benign.

However, when one turns to the appendices—half of the full Report—the drafters treat religion, and specifically Christianity, like a jack-in-the-box toy in the hands of a toddler on a sugar high.

In Appendix II (“Faith and America’s Principles”), the pluralistic notion of religion that the Report had employed up to this point gives way to a considerably more exclusive treatment of religion as Christianity. This shift is subtle but significant. The section argues that Christian faith was fundamental in the founding and early success of the nation. Without Christian leaders, the American Revolution might not have succeeded (p.26), and Christian principles proved “essential to the new experiment in self-government and republican constitutionalism” (p.27). While all faiths are entitled to religious liberty, it is “biblical faith” that undergirds the “proposition of political equality … [and] is the deepest reason why the founders saw faith as the key to good character as well as good citizenship, and why we must remain ‘one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all’” (p.28).

Throughout all the appendices, Christianity pops up only ever as a force for good in American history, then immediately disappears in any attempt to diagnose the “Challenges to America’s Principles.” Nowhere is this more evident than when the Report discusses the abolition of slavery and the movement for African American civil rights.

In the Report’s telling, Christianity and its God were squarely on the side of the abolitionists and civil rights marchers as they battled against otherwise secular foes—“white supremacists” (no mention of religious affiliation) and the “forerunners of identity politics.” Abolitionists, for example, “drew on the Bible” in their “crusade against race-based slavery in the colonies” (p.26). The drafters of the Report also take great pains to absolve the founders from any connection to slavery: “Yet as we condemn slavery now, we learn from the founders’ public statements and private letters that they condemned it then. One great reason they published the Declaration’s bold words was to show that slavery is a wrong according to nature and according to God. With this Declaration, they started the new nation on a path that would lead to the end of slavery” (pp.34-5). Nowhere is there mention of the fundamental role of Christian proslavery arguments that provided the intellectual framework for the institution of slavery in the antebellum South, nor of the theological crisis that ensued in Christian churches as a result of the Civil War.

When the Report comes to the Civil Rights Movement, it suggests that the “tireless effort to end Jim Crow and extend civil and voting rights to African Americans and other minorities was driven by clergy and lay faithful of a multitude of denominations, including most prominently the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.,” to whom more religious significance is given than any other figure in the Report. In fact, the Report makes the bold claim that “America’s greatest reform movements have been founded or promoted by religious leaders and laypersons reared in faithful home environments,” providing several examples—all of them Christians. Once again, there is no mention of the considerable opposition that segregationist theology posed to the Civil Rights Movement.

Indeed, for all the references the Report makes to Frederick Douglass (seven times) and Martin Luther King Jr. (eight times) surrounding the issues of slavery, racism, and civil rights, its drafters conveniently left out their repeated and biting critiques of White Christianity and its complicity in the sins of slavery and anti-Black racism.

In the end, the “jack-in-the-box” game the Report plays with religion is not just sloppy historical scholarship by a committee of untrained historians—which it certainly is—but a subtle-but-sinister revision of American history vis-à-vis Christianity. Unlike the “everywhere and nowhere” problem with professional American historians, which results mostly from a lack of appreciation for the role of religion in shaping American history, the jack-in-the-box faith of the 1776 Report is not an accident or oversight. Rather it seems to be a calculated attempt to wed a purified version of the nation’s founding—absolving the founders of the sin of slavery and sacralizing its founding documents—with a triumphant vision of Christianity as foundational and faultless in the project of American exceptionalism. The end result is a Report that lays the groundwork for a version of American history that reflects the concerns, beliefs, and anxieties of Christian Nationalism.

Published by the Trump administration less than two weeks after the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, the 1776 Report effectively gives a nod of approval to the Christian Nationalists who rioted on the Capitol Building’s steps, invaded the People’s House, and then prayed together on the Senate floor. Held up against the standards of historical scholarship, the Report is laughable, but this doesn’t mean we can therefore ignore it or that it’s not dangerous. History, when responsibly studied—providing a balanced and honest record of humanity’s achievements and shortcomings—has the potential to help us “form a more perfect Union.” It can expand our minds and our hearts, but it can also be weaponized to narrow them.

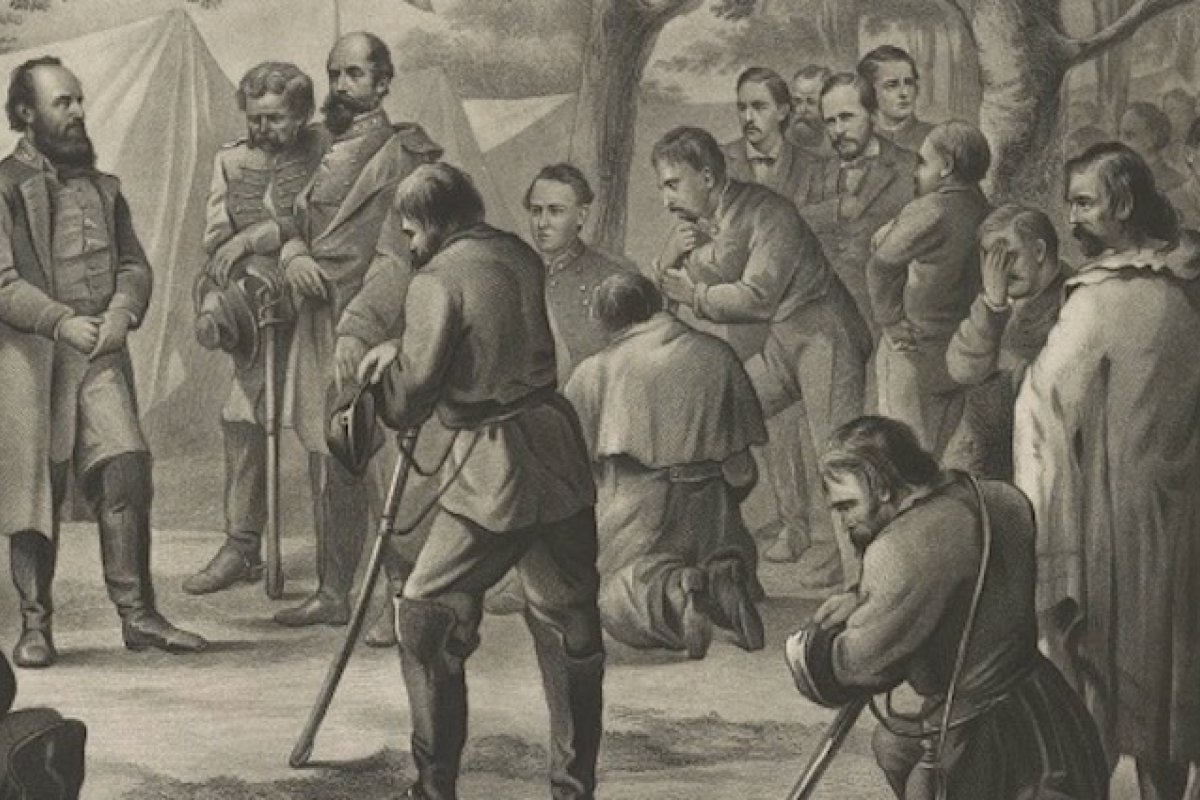

Image: "Prayer in Stonewall Jackson's camp" (J.C. Buttre, 1866, via Library of Congress); engraving depicting a scene from the Confederate States Army Revival.

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.