What's Ressentiment Got to Do with It

Should our republic and, with it, its kin in Western Europe survive, any and all attempts to transcend the current chaos will have to begin with, or at least include, diagnosis and analysis of what got us here

Should our republic and, with it, its kin in Western Europe survive, any and all attempts to transcend the current chaos will have to begin with, or at least include, diagnosis and analysis of what got us here. Whoever reads the internet messages, editorials, and serious books on our culture(s), whoever listens to the pundits, philosophers, and ranters, will come across numberless references to inter-class (and other “inter-”) phenomena such as “revenge, hatred, malice, envy, the impulse to detract, and spite.” These are not new in politics, religion, or culture, but, taken together, they appear to be grounded in profound, bone-deep, soul-destroying resentment, and are efficiently mobilized by modern media, on the internet, and with expensive advertising. The analysts point to the special character of our current explosions and often render their view technical by using the French word ressentiment.

Should our republic and, with it, its kin in Western Europe survive, any and all attempts to transcend the current chaos will have to begin with, or at least include, diagnosis and analysis of what got us here. Whoever reads the internet messages, editorials, and serious books on our culture(s), whoever listens to the pundits, philosophers, and ranters, will come across numberless references to inter-class (and other “inter-”) phenomena such as “revenge, hatred, malice, envy, the impulse to detract, and spite.” These are not new in politics, religion, or culture, but, taken together, they appear to be grounded in profound, bone-deep, soul-destroying resentment, and are efficiently mobilized by modern media, on the internet, and with expensive advertising. The analysts point to the special character of our current explosions and often render their view technical by using the French word ressentiment.

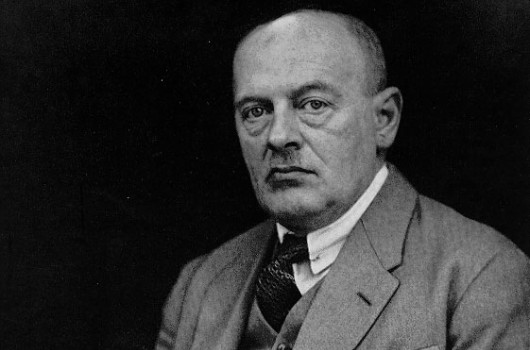

Modern-day users of that term draw upon big-deal thinkers such as Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Weber, and Sartre, but prime among them is the German philosopher Max Scheler (1874-1928), author of the 1912 book Ressentiment, which has most informed my outlook through the years since it first came out in English in 1961. Scheler’s widely quoted definition of ressentiment, one that illuminates an important aspect of the world of political, cultural, religious, and social leaders and folk, reads: “Ressentiment is a self-poisoning of the mind... It is a lasting mental attitude, caused by the systematic repression of certain emotions and affects which, as such, are normal components of human nature. Their repression leads to the constant tendency to indulge in certain kinds of value delusions and corresponding value judgments. The emotions and affects primarily concerned are [as quoted above] revenge, hatred, malice, envy, the impulse to detract, and spite.”

So much for tolerance, civility, empathy, mutuality, and dialogue!

Examples: people in one class or region or situation, encouraged by their chosen leaders, nurture ressentiment as “the repeated experiencing and reliving of a particular emotional response reaction against someone else.” International Islamophobia is one instance of this. Scapegoating globally is another. People will even vote against their own interests, or redefine their most cherished religious beliefs, because they are victims of ressentiment. “Populist” and “elitist” are the emergent names favored by workers, voters, academics, and religious people with reference to others. One finds evidence of this in international Catholic controversies, which the Pope is trying to cool. In the United States it is manifest even in fracturing Evangelicalism. “Populists” who suffer job losses because of automation, changes in marketing, the closing of mines, and “globalization” look for villains to blame, and turn to those who promise easy solutions. “Elitists” take refuge in celebrity worship, which fails them, and, as tastes change, ressentiment takes over. Read the spiritual and mental temperatures that led to Brexit, and which have only begun to afflict once civil nations that now see themselves as being overrun by refugees, who are regarded as terrorists, not to mention the charges leveled at their domestic hosts and welcomers.

Again, if our republics survive, they must welcome analysis, but they will also need more. In these years of chaos, Sightings sees as ever more urgent the work of civil volunteers, humanitarians, religious providers of opportunity, humane activists, plus re-readers and expounders of the texts that first denounce those situations which give rise to ressentiment and then manifest what one scripture calls “the more excellent way” of love. These appear here and there, against all odds, and deserve fresh and sustained hearing and response.

Resources

- “Ressentiment (Scheler).” Wikipedia. Accessed February 5, 2017.

- Scheler, Max. Ressentiment. Ed. Lewis A. Coser. Trans. William W. Holdheim. Marquette University Press, 1994.

Image: Max Ferdinand Scheler (1874-1928)

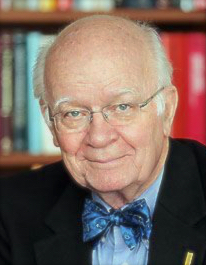

Author, Martin E. Marty, is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. Author, Martin E. Marty, is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of the History of Modern Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School. His biography, publications, and contact information can be found at www.memarty.com. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco, a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Subscribe to receive Sightings in your inbox twice a week. You can also follow us on Twitter.