Will D. Campbell: An Unconventional Approach to Racial Reconciliation — Jeff Jay

Several events this past summer brutally reminded everyone that race is still a volatile issue in America fifty years after Dr

By Jeff JayOctober 10, 2013

Several events this past summer brutally reminded everyone that race is still a volatile issue in America fifty years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. Tense conflicts followed one after another: food-show host Paula Deen's use of racist language, the Supreme Court's invalidation of part of the Voting Rights Act, and then (as if these events were not staggering enough) George Zimmerman's acquittal for shooting Trayvon Martin.

Several events this past summer brutally reminded everyone that race is still a volatile issue in America fifty years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. Tense conflicts followed one after another: food-show host Paula Deen's use of racist language, the Supreme Court's invalidation of part of the Voting Rights Act, and then (as if these events were not staggering enough) George Zimmerman's acquittal for shooting Trayvon Martin.

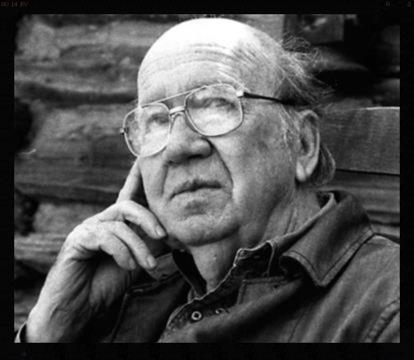

Still another event, one that strongly evoked the fight for civil rights, though far less noted in the media than the others, is deserving of reflection—the death, at 88, of the Reverend Will D. Campbell on June 3, 2013. News coverage of Campbell's death rightly extolled him as a major civil rights activist and significant writer whose Brother to a Dragonfly was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1978.

Yet many analysts as well as his friends are also grappling with what the New York Times calls his "knot of contradictions." The coverage in the news describes him variously (yet accurately) as a "profane minister," "a Southern Baptist who drank moonshine with the Catholic nuns he counted as his friends," and a "country boy…uttering streams of sacred and profane commentary."

At the heart of this knot is the fact that he was, in his close friend Bernard Lafayette's words, "the civil rights chaplain for the Ku Klux Klan," which was enough in the 1960s and 1970s to inspire hate from conservatives and liberals alike.

Campbell's impressive record as an activist more than confirms his right to the title of "civil rights chaplain." In 1957 he was the only white participant who joined Dr. King at the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. Soon afterwards Campbell escorted black students through angry protestors decrying the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. He also joined the Freedom Riders in 1961 and accompanied Dr. King for the marches in Birmingham in 1963 and in Selma in 1965.

And yet Campbell's record equally certifies him as the bona fide "chaplain for the Ku Klux Klan." He is remembered for visiting the noted racist, James Earl Ray, in prison after Ray assassinated Dr. King in 1968.

How did Campbell hold these contradictions together? The media coverage is quick to highlight the incongruity, but rarely ventures into Campbell's rationale.

Central for Campbell was the concept of "reconciliation." He developed this concept in regular contributions to Katalagete: Be Reconciled, the flagship journal for the Committee for Southern Churchmen, of which Campbell was the director. Claiming as his own a "ministry of reconciliation," a phrase he borrowed from 2 Corinthians 5:18, Campbell argued that social change does not come solely through legislation and government-led initiatives. Lasting justice, he held, can prevail only on the basis of genuine reconciliation between people who are normally at odds.

Once challenged by a friend to summarize the Christian message in ten words or less, Campbell emphasized God's unconditional love, "We're all bastards, but God loves us anyway" (Brother to a Dragonfly, 220).

Campbell took this vision of reconciling with bastards and put it into action, ultimately allowing it to shape his provocative position on the KKK. It became necessary in Campbell's view to extend compassion, grace, and forgiveness to everyone, including bigots, especially violent ones. Members of the KKK deserved compassion, he explained, because many of the Southern whites who flooded its ranks were themselves the victims of dire poverty, which he terms "the redneck's slavery." Campbell argued that theirs was a tragic history of a repressed people, who were, notably, also Campbell's own (he grew up in rural Mississippi during the Depression).

At one point Campbell went uncomfortably far when he wrote of poor rural Southern whites: "They had been victimized one step beyond the black." Elsewhere, he declared, "I'm pro-Klansmen because I'm pro-human being" (Brother to a Dragonfly, 226, 244).

Is this taking "reconciliation" too far?

Or is this what truly made Campbell, as former President Jimmy Carter described him, "a minister and social activist in service of marginalized people of every race, creed and calling"?

One of Campbell's fellow Freedom Riders, John Lewis, who is black, is now a member of the U.S. Congress (D-Georgia). In 2009, Rep. Lewis met in his Washington office with Elwin Wilson, who had supported the KKK and had joined a group that attacked a bus of Freedom Riders in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Wilson asked Lewis for forgiveness, which Lewis granted. Reportedly, tears fell from both men's eyes.

It was a "Campbellian" moment. Is such a moment still possible in today's climate?

References:

Anderson, David E. "Feisty Civil Rights Activist Will Campbell Dies at 88." Washington Post, June 5, 2013. Accessed October 7, 2013. http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/on-faith/feisty-civil-rights-activist-will-campbell-dies-at-88/2013/06/05/b752fed4-ce1a-11e2-8573-3baeea6a2647_story.html.

Campbell, Will D. Brother to a Dragonfly. New York: Continuum, 1977.

Campbell, Will D. Writings on Reconciliation and Resistance. Edited by Richard C. Goode. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2010.

Johnson, M. Alex. "Civil Rights Warrior Will D. Campbell Dies at 88." NBC News, June 3, 2013. Accessed October 7, 2013. http://usnews.nbcnews.com/_news/2013/06/05/18762081-civil-rights-warrior-will-d-campbell-dies-at-88?lite.

McFadden, Robert D. "Rev. Will D. Campbell, Maverick Minister in Civil Rights Era, Dies at 88." New York Times, June 4, 2013. Accessed October 7, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/05/us/will-d-campbell-maverick-minister-and-civil-rights-stalwart-dies-at-88.html?pagewanted=all.

Pitts, Leonard. "Proof That Love Can Overcome Evil." Tampa Bay Times, April 3, 2013. Accessed October 7, 2013. http://www.tampabay.com/opinion/columns/column-proof-that-love-can-overcome-evil/2112908.

Image Credit: Religion News Service.

Author, Jeff Jay, is Visiting Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at St. Norbert College in De Pere, Wisconsin, and a graduate of the University of Chicago, Divinity School (Ph.D., Bible, 2013).

Author, Jeff Jay, is Visiting Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at St. Norbert College in De Pere, Wisconsin, and a graduate of the University of Chicago, Divinity School (Ph.D., Bible, 2013).

Editor, Myriam Renaud, is a Ph.D. Candidate in Theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School. She was a 2012-13 Junior Fellow in the Marty Center.

Editor, Myriam Renaud, is a Ph.D. Candidate in Theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School. She was a 2012-13 Junior Fellow in the Marty Center.