This is the Way: Daoist Themes in Star Wars

Return of the Jedi resonates with themes, ideas, and symbolism from real-world religious traditions.

Today is May 4th, celebrated widely as Star Wars Day. May the Fourth be with you.

This month, Star Wars enthusiasts—and their begrudging-but-supportive partners—have the opportunity to go to theaters to watch Return of the Jedi (1983) on the fortieth anniversary of its release.

The epic conclusion of the original Star Wars trilogy, Return of the Jedi may not seem at first glance like it has much to do with religious studies (except, perhaps, for the scene where the Ewoks worship C3PO). Nonetheless, Return of the Jedi resonates with themes, ideas, and symbolism from real-world religious traditions, in particular Daoism.

This may not just be happenstance. George Lucas, creator of the Star Wars universe, said that he tried to distill elements from various religions to craft the mythology of the Star Wars films. The character Yoda (whose name likely comes from the Sanskrit word for “warrior”) was inspired by George Lucas’s time with Buddhist monks in India as well as mentor characters in Japanese samurai movies. Lucas drew not only from his own Methodist upbringing but from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which retells and reinterprets stories from several religious and folkloric traditions.

If Lucas’s goal was to craft a new myth that resonated with the old myths, he has been successful. As he observed, “When the film came out, almost every single religion took Star Wars and used it as an example of their religion; they were able to relate it to stories in the Bible, in the Koran, and in the Torah.” My students and I explore these parallels in the class “Star Wars and Religion,” putting stories of saints, sages, and bodhisattvas into conversation with the most popular film franchise of the last half-century. Though we are much less confident than Lucas and Campbell that religions teach generally the same truths or that hero stories share the same structure, we find that Star Wars movies serve as a helpful point of comparison for the moral and metaphysical emphases in Christianity, Buddhism, and Daoism.

Classical Daoist texts like the Daodejing, the Zhuangzi, and the Liezi can be interpreted many different ways, and yet some thematic links emerge when one reads these texts together. One point is how apparent opposites tend to transform into one another. Day is always in the process of turning into night, and night is always turning into day. The logic of opposition by which we customarily make sense of the world leads us astray. The sage moves in tune with the shifting rhythms of the world rather than trying delusively to cling to one side of a dichotomy.

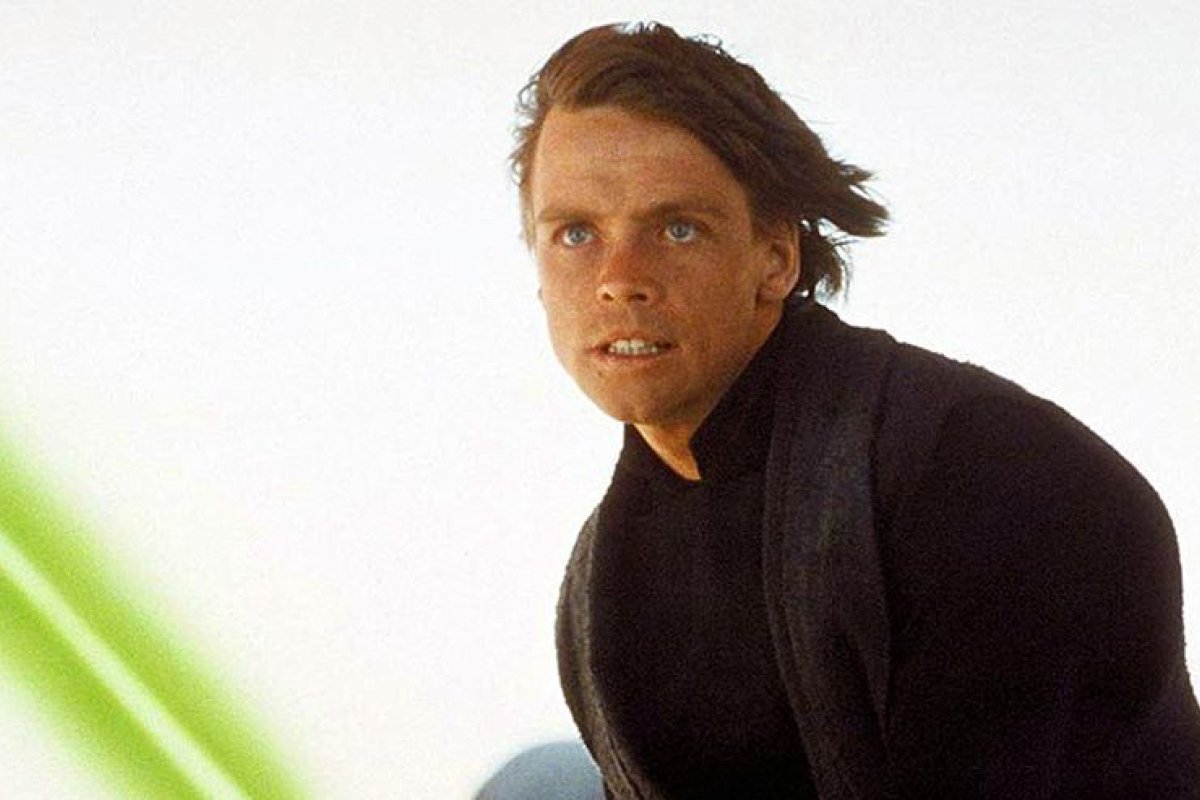

At the beginning of Return of the Jedi, the hero Luke is more like the villain Darth Vader than ever before—he’s wearing black, and he uses the Force choke, Vader’s signature move. Viewers also see a scene where Luke’s mechanical hand is exposed after being shot on Jabba’s barge, the mechanical hand that symbolically links him to Vader. The effort to overcome the Dark Side has made Luke more like his enemy than ever before.

A principal exhortation in Daoist literature is to abandon the illusion of having control over outcomes. Chapter 7 of the Zhuangzi says, “Not doing, not being a repository of plans and schemes. Not doing, not being the one in charge of what happens.” The way of the sage is much closer to improvisational jazz than to the execution of a predetermined plan. In Return of the Jedi, the Emperor, the archvillain of the film, continually talks about “destiny.” He is confident that everything will turn out exactly as he has foreseen it, that his plans will come together, and that he is in control of exactly what is happening. In this is his undoing—as Princess Leia said in an earlier film, “the more you tighten your grip, the more star systems will slip through your fingers.”

Daodejing 43 says “The softest things in the world run roughshod over the firmest things in the world.” In contrast to the controlling, technological Empire, the unexpected champions in Return of the Jedi are the Ewoks, who live in harmony with the natural order. The notion that the natural has more power than the mechanical can be found in classical Chinese thought more generally and Daoism in particular, as can the idea that what is devalued can triumph over what is valued.

Finally, and most significantly, the climactic moment in Return of the Jedi is Luke’s choice to turn off his lightsaber. At the end of the film, Luke looks down at the severed robotic hand of his father, then at his own robotic hand, recognizing that there’s greater similarity between himself and his apparent opposite. (Think about the bit of yin within yang and the yang within yin in the well-known Taiji diagram.) In that moment, the logic of opposition ceases to dictate the conflict. When facing Darth Vader for the last time, Luke refuses to keep fighting, just like Obi-Wan did on the first Death Star. He turns off his lightsaber and casts it aside. Here, the most important doing is a non-doing, wu-wei in Chinese.

The Zhuangzi says, “The mass of men, regarding something as unnecessary, try to force it to conform to how they think things must be, and thus they always need many weapons…. But thus to rely on weaponry and war is to destroy oneself.” The Emperor promises Luke one kind of power, the power to control the galaxy, but Luke’s power, his te or virtuosity, comes from not resisting. Luke acts by not acting, and the Empire collapses in on itself. Chapter 69 of the Daodejing says, “There’s nothing worse than attacking what yields. To attack what yields is to throw away the prize.” This is the lesson Luke has learned. By refusing to fight, he wins the battle.

Image from Star Wars press kit