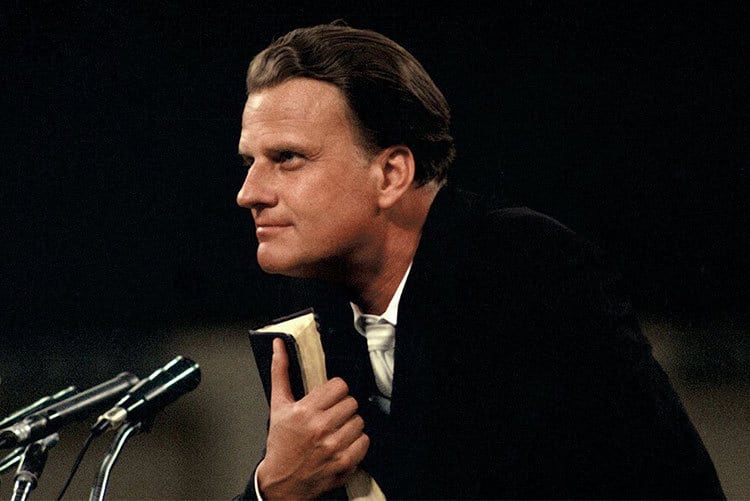

They Called Him Billy

Several years ago, my wife, Katherine, and I spent a week researching letters that Americans sent to the evangelist Billy Graham, who died in 2018 at age 99

Several years ago, my wife, Katherine, and I spent a week researching letters that Americans sent to the evangelist Billy Graham, who died in 2018 at age 99. One day we stumbled on an undiscovered cache of children’s messages. They provide a window into Graham’s remarkably wide appeal.

Several years ago, my wife, Katherine, and I spent a week researching letters that Americans sent to the evangelist Billy Graham, who died in 2018 at age 99. One day we stumbled on an undiscovered cache of children’s messages. They provide a window into Graham’s remarkably wide appeal.

Most of the letters’ authors were seven to eleven years old, and often addressed the evangelist with his full name, but also very often, just as Billy. He offered them a safe space for sharing their fears and hopes. And he played multiple roles in their lives, including friend, confidant, and trusted advisor.

Indeed, when Graham appeared on television in their living rooms, he became not just a friend but part of the family. Kids shared detailed information about themselves (weight, height, exact age, down to the month) as well as their siblings and parents. They also shared family trade secrets. One author, Russ, let Billy know that his whole family was “going organic.”

Not surprisingly, pets held a warm spot in the hearts of these children, and they wanted to share those feelings with Billy. Matt happily reported that his dog had “just turned Christian.” But worries arose too, especially when it came to their beloved pets’ deaths. Andrea said it as simply and clearly as language permitted: “I hope my cat went to heaven.”

But Billy was more than a friend. He was a confidant, and some openly aspired to follow in his steps. “Almost every day I crave to preach in front of one million people,” John allowed. “I might be another Billy Graham.” No wonder. Not a few believed that Graham had a special relationship with the Lord. “How is God doing?” little Shirley wondered. “Jesus is lucky to have a man like you,” Scott judged.

And then there was the role of advisor. The young folk who wrote to Graham trusted him to tell them the truth. Hilton needed clarification. “You said on your show that to love the world is a sin. I love animals and the animal world, is that a sin?” At first glance, some questions seemed superficial but at bottom proved to be weighty ones of theodicy. Karen wondered: “what do you do when you pray and your fish does not get well?” The issue was not trivial. It demanded a response. “Write me back.”

None of the children used the word “epistemology,” but children needed assurance. Alice cut to the heart of the issue. “I know that if the lord was not real how could we move. I know the Lord is real for I can feel him in my blood.” Not fancy, but concise and clear.

Many letters could be slotted into the chapters of a textbook in systematic theology. Sin figured large, not sin in the abstract, but sin in their own hearts. Lois, a rising teenager, was a bit older than most but spoke for many. “[My life] was routen. I use to talk with boys that sware and say bad words and lie. I did things I shouldn’t.” But if sin abounded, so did grace. “I love everyone but I love Jesus more,” said one young soul, barely able to contain her joy.

All this was good news, and it was meant for everyone. “God loves white and red and black and brown,” one earnest heart shared. David invited Graham to hold a crusade at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia—located at Broad Street and Pattison Avenue, he carefully noted—because, “Who needs it better than Philadelphia?”

Young authors felt the inevitable passing of time. “I pray that God will keep you alive for a hundred years,” wrote Danielle. Kate put the point as precisely as possible: “Don’t die until there’s someone to take your place.” In their innocence kids somehow sensed that Graham was unique—and irreplaceable.

The closings that children used for their letters spoke volumes about their feelings for Graham. “Your buddy.” “So long.” “Praise you.” “God bless you.” “Your unknown friend.” “A Grate fan of yours.” But by far the most frequent one consisted of just one word: “Love.”

We know that in the United States, at least, the majority of Graham’s followers were white lower-middle-class residents of small or medium-sized towns in the South and Middle West. Kids too. Their letters represented only a slice of American public life, but a slice rich with religious meaning.

Martin Marty recently said that on the Mt. Rushmore of American religious history, four figures hold a secure spot: Jonathan Edwards, Martin Luther King, and Billy Graham. (Marty added, with a characteristic wink, that he had not yet decided on the fourth.)

No wonder. Among many contributions, Graham offered millions a message of a second chance. He helped children know that no matter how badly they—or their parents—had messed up their lives, they still had an opportunity to make things right. He also helped them know that God loved them. They called him Billy because they sensed that he did too.

Author, Grant Wacker, is the Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Christian History at Duke Divinity School, and he is the author of the just-released biography, One Soul at a Time: The Story of Billy Graham (Eerdmans, 2019), from which this essay was adapted with permission by the publisher. Author, Grant Wacker, is the Gilbert T. Rowe Professor Emeritus of Christian History at Duke Divinity School, and he is the author of the just-released biography, One Soul at a Time: The Story of Billy Graham (Eerdmans, 2019), from which this essay was adapted with permission by the publisher. |

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in America at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email.