Smart Sightings | The Religious Experience of Mark Rothko

Can art and the experience of art be divine? Mark Rothko's "No. 2" offers alternative ways to think about religion.

“Smart Sightings”is a new partnership between the Marty Center and the University of Chicago's Smart Museum of Art. This series invites readers to contemplate the many connections between art and religion through written reflections on pieces in the Smart’s exhibition, Calling on the Past: Selections from the Collection, on display at the museum from March 21, 2023 to February 4, 2024. Featuring illuminating pairings of objects from the museum’s permanent collection, Calling on the Past encouraged viewers to see the collection—and themselves—with fresh eyes.

Mark Rothko’s “No. 2,” 1962 is a key object in the Smart Museum of Art’s permanent collection and a central piece in its recent exhibition Calling on the Past. Although it may not seem so at first glance, the painting and Rothko’s work more generally offer a productive opportunity to reflect on the study of religion.

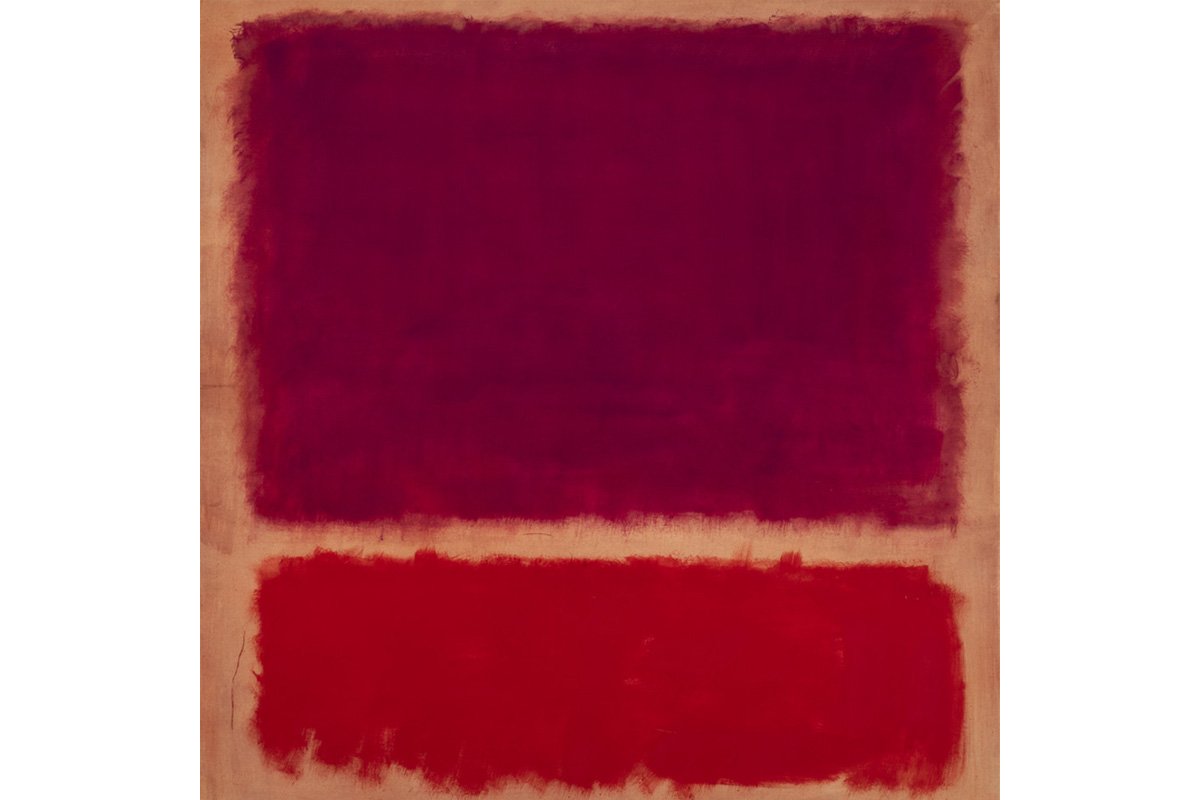

As with so much of Rothko’s work, “No. 2” immediately confronts the viewer with its size and color. The large canvas is painted in two vertically-aligned rectangular forms—an almost square block of electric magenta over a thinner block of vibrant red. These hyper-saturated shapes float against a bright field of golden tan. From afar, each of the colors appears internally uniform, while the shapes appear to have sharp boundaries. As one moves toward the canvas, variations in the depth of color and the soft imprecision of those boundaries become visible. Some areas of the canvas are slightly translucent, allowing glimpses of the background through the purple and red, while others are so saturated as to be nearly opaque. This is evidence of Rothko’s color wash technique, in which very thin applications of paint are layered unevenly over one another to create texture and luminosity.

For many viewers, the visual confrontation with Rothko’s paintings is followed by the emotional impact of that confrontation—an affective response to the abstract collaboration of color, tone, size, shape, depth, structure, and composition. The first time I saw one in person, I was surprised to find myself utterly overwhelmed with emotion. I felt engulfed in a way that was at once comforting and startling, intimate and yet immense, limitless. The lack of familiar contours and context—no figuration, no narrative, no explanation or suggestion of where to begin or end—evoked a visceral sense of wonder and possibility. It was only when a stranger asked me if I was okay that I realized I was crying.

Rothko was aware that his paintings evoked deep emotion in his viewers and it was this fact, more than the formal compositional elements of his pieces, that held meaning for him as an artist. He reportedly once said to art critic Selden Rodman, “I am not an abstractionist… I’m not interested in relationships of color or form…. I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on—and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions… The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you… are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point!”

Rothko’s mention of a “religious experience” is interesting and deserves further reflection. The idea of “religious experience” has been important to scholars of religion for centuries. Many have considered it to be religion’s most essential feature. The German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, for instance, defined religion as the occurrence of a feeling of “absolute dependence” on God. For Rudolf Otto, religion was the experience of awe, dread, terror, and fascination in the face of “the numinous,” an entity that is entirely other than oneself. In The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James writes that religion is “the feelings, acts and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider divine.” For Mircea Eliade, religion was defined as “the experience of the sacred,” a personal confrontation with a universal, more-than-human force that animated reality and history.

For these scholars, the core of religion was a confrontation with the divine, the sacred, or the more-than-human that produced an individual, internal, transformational experience, one often characterized by overwhelming emotion. Religious experience was the antidote to disenchantment, the enemy of alienation. It was beyond the rational, unavailable to scientific investigation, inaccessible to critique.

Rothko’s idea of religious experience simultaneously borrows from and resists these sorts of definitions (definitions that tend to emerge where frameworks of thought and language are deeply entwined with Protestantism). On the one hand, he maintains that religious experience is an internal, non-rational, highly emotional encounter. But unlike the theorists discussed above, Rothko does not characterize the object of that encounter as God, the divine, the sacred, or any entity posited as more than human. Instead, for Rothko religious experience (at least in the above quotation) is explicitly human. It is human emotion, born from the encounter with something entirely of this world: wood, canvas, water, and paint brought together by human hands and human creativity.

What I find intriguing about Rothko’s usage is that it offers us the opportunity to think beyond an essentialist notion of religion that requires a conventional higher power. It thus inspires all kinds of fascinating questions: Can art and the experience of art be divine? Can human emotion? Do we need only the best qualities of the self—creativity, generosity, openness, humility—to experience the sublime? If art can be a site of “religious experience,” do we need the other, institutional trappings of religion.

Rothko was raised in an atheist Jewish family and was heavily influenced by myth, mysticism, and Christian art. His work was often described by critics as spiritual or sublime and one of his last commissions was for an interfaith chapel. Still, his concern for “religious experience” is not bound to a specific tradition. Our understanding of his work need not be, either. Instead, Rothko’s “religious” paintings can allow us to re-think and re-imagine religion as a broader conceptual category, one that extends beyond conventional Protestant definitions. Religious experience might include transformative enchantment in the face of beauty, moments of self-transcendent or profound self-knowledge, or feelings of intense belonging in a larger social or cosmic whole. Or it may simply mean that the experience of art is “sacred” in the most basic sense of the word: that it is “set apart,” distinct from the mundane and the everyday. What’s most important to me as a scholar of religion is that paintings like “No. 2” offer us data for examining our own and others’ assumptions about what religion is and is not, and what such assumptions might tell us about who we are, what we hope for, and what kinds of worlds we want to make possible.

Featured image: Mark Rothko, No. 2, 1962, Oil on canvas. Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Gift of Mrs. Albert D. Lasker, 1976.161.