Sharpiegate, or the Origins and Ends of Democracy

What does #Sharpiegate teach us about the place of religion in the future, or the end, of democracy?

During the summer hiatus of Sightings, the world kept spinning while hunger, poverty, horrific natural disasters, like Hurricane Dorian, continued to trammel human life. Politicians continued to vie for power, the Amazon burned and the planet heated up, while thousands poured into the streets of Hong Kong struggling for self-determination. President Trump tweeted and retweeted, ordinary folks kept working, a trade war bore down on farmers with some driven to take their lives, and there was the fear of “Christian replacement” by immigrants and others. Such are the realities of everyday life, and each reality can be seen, with a little perspective, as a “sighting” of religion.

So where is a Sightings columnist to begin? “Sharpiegate”?

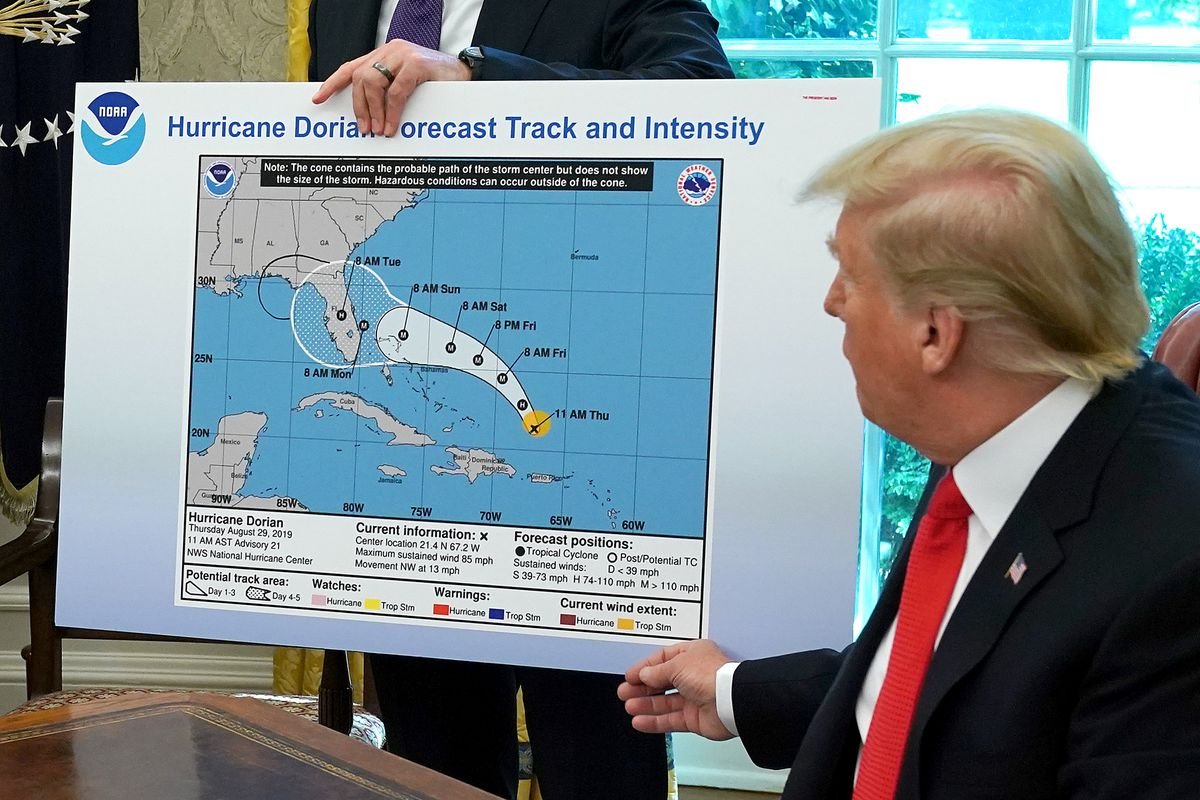

The rise of populism within democratic states has provoked endless discussions about the “end” of democracy. Drawing on the work of Steven Levitsky and Daniel Zieblatt in How Democracies Die, a work which traces in various nations the erosion and collapse of institutions meant to safeguard democratic governance, the economist Paul Krugman has recently extended the analysis to the United States. One instance of institutional erosion he highlights is the bizarre set of events surrounding President Trump’s apparent altering of a map that projected the path of Hurricane Dorian. Critics and comics responded caustically to “Sharpiegate,” as it was dubbed. “But,” wrote Krugman, “it stopped being any kind of joke on Friday, when the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued a statement falsely backing up Trump’s claim that it had warned about an Alabama threat.” Also dangerous is the attack on automakers who are trying to hold onto environmental standards for gasoline mileage set during the Obama administration. Even clean water is now under assault. Because environmental and other institutions seem corroded, people around the world worry about the durability of democratic self-governance.

The main threat nowadays to democratic governance is not from, say, an “external” invasion, but the internal corrosion of institutions meant to stave off tyrannous forces. Recall that thinkers like Alexis de Tocqueville and others argued that democracy in America relies on institutions (like the press), specific vocations (like lawyers), and the mores of the culture continuing to draw strength from religious traditions. As Anne Applebaum has put it, “The crisis of Western values has many aspects, many faces. There is a decline in faith in liberal democracy, a loss of confidence in universal human rights, a collapse in support for all kinds of transnational projects.” Some evangelicals cling to the idea that Trump is a modern King Cyrus while among other folks, progressive and conservative, “liberal” has become a dirty word.

Ancient thinkers believed that any democracy would undo itself. Aristotle, for instance, held that rule by the people, the demos, would undercut the rule of law. An aristocracy was thereby a more stable form of governance, especially if the “best” ruled the rest of the citizens. The deeper question before us, it would seem, is whether or not people actually want self-rule, and, further, if the current “dying” of democracy is in fact people’s answer to that question.

Yet if one casts an eye to the global scene, it would seem that we are, in fact, witnessing not one but two “ends” of democracy. One end is the dying of democracies in the grip of populism (in fact a plutocracy). The other “end”—a goal—is on the streets of Hong Kong and among young people working for stricter gun laws and sane environmental policy. Here the “end” of democracy is the aim of actual self-governance.

Aspects of the debate about the ends of democracy have pervaded public conversation for some time now. What grabbed my attention recently is where those conversations intersect with another pervasive topic, the political origins of American democracy. There are advocates of different stories about the origin of democracy in this nation. Some champion its Puritan origins and the search for religious freedom. Others note the grounding of central ideas within European Enlightenment thought, broadly understood. And still others point to Roman Republicanism. So, disputes about the place of “religion” in the struggle for self-rule range from those who ardently deny its role to those who hold that we have been and must remain a “Christian Nation.” Of course, no single line of thought tells the whole story, but at issue is the place of religion, of whatever sort, in democratic public life here and around the world.

Recently, a new voice has joined the debate. Eric Nelson, Harvard political scientist, argues that Christian and Enlightenment thinkers admired and drew on Hebrew thought—the division of the nation into tribes, a kind of balance of power, equality of peoples created by God from the four corners of the earth, and the rule of law—in order to develop their own political theorizing. If this is right, and there is an excellent case for it, then the origins of modern Western democracies are richer and more diverse than is often granted. (See also this piece by Eric Herschthal.)

What about the overlap of these ideas about origins and ends? Could it be that sightings of religion in debates about the origins of democracy are a distraction? After all, the origin of some political conception does not assure its truth or livability. Debates about origins can easily sideline the pressing question of which end we are racing towards. What is more, claiming a place in the story of origins elides the question of whether or not religious sources can once again fund the struggle for the self-rule of peoples or if they pave the path of subservience to demagogues and tyrants where the best do not in fact rule the rest. We need to look for sightings of religion in the muddle of everyday life, and not just in mythological origins or apocalyptic ends.

Amending Reinhold Niebuhr, therefore, we might say that the human drive for self-rule makes democracy possible while human complacency makes it necessary. The question played out around the world is whether religions energize or sedate peoples’ capacities to conduct their own lives.

| Columnist, William Schweiker (PhD’85), is the Edward L. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of Theological Ethics at the Divinity School. |

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School, with assistance from Nathan Hardy, a PhD Candidate in the History of Christianity at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.