The Return of Franz Bibfeldt

Bibfeldt’s return invites us to remember that there is an essential place for the occasional fit of laughter in even the most scholarly house.

A Note From the Editors: Protests from Bibfeldtians – from the bemused to the mildly dismayed – have prompted the author to acknowledge that much of the material in this essay is drawn from The Unrelieved Paradox: Essays on Franz Bibfeldt, ed. Martin E. Marty and Jerald C. Brauer, 18th (or perhaps 19th) Anniversary Revised Edition, published by the venerable Eerdman’s Press in 2006. This is particularly true of the author’s earlier Forschungsbericht, “Franz Bibfeldt: The Life, and Scholarship on the Life,” included therein.

The chief academic sin is arrogance, and its best corrective is laughter. As a graduate student grappling with the authoritative emergence of deconstruction in the early 1980s, no novel was so tonic – or taught me so much – as David Lodge’s Small World, a knowingly hilarious send-up of the regnant theoretical gambit among literary critics at the time. Like Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim for historians of an earlier generation, Small World participates in its moment and does not age as well as, say, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. But Lodge, Amis, and Swift each aimed to address the foibles and faults of their context that complexly balanced respect for institutions with an eye on their failures to live up to their ideals. Each also assumed that goal would be best accomplished by eliciting laughter.

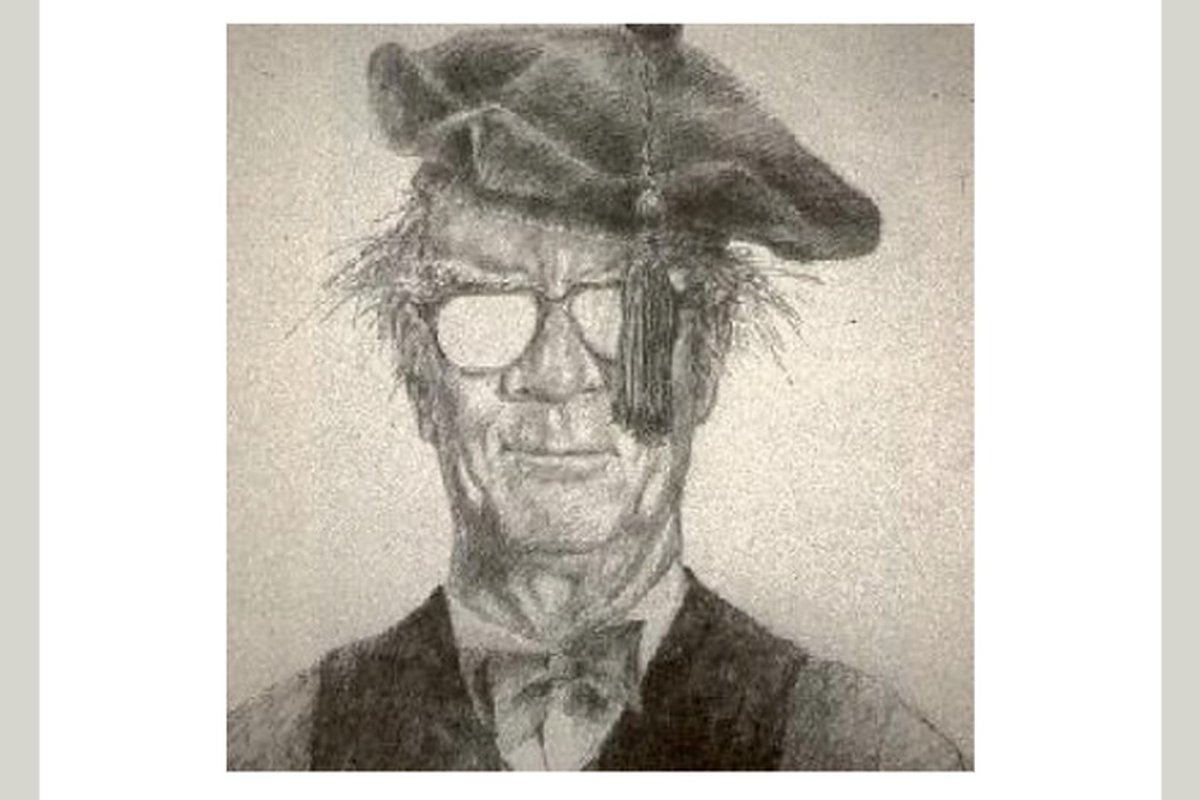

Sightings' most enduring and significant contributor, Martin E. Marty, embodied this impulse as a seminarian in the late 1950s when he and several of his colleagues began to insert cards in the library’s card catalog and footnotes in their course papers citing the writings of Franz Bibfeldt. Soon a reference point in classroom discussion and the seminary’s student newspaper, Bibfeldt was invoked by credulous faculty and students eager to be up-to-date with the most current scholarship in an amazingly wide variety of fields (theology, biblical studies, the history of Christianity, effective modes of pastoral care, etc.).

The emergence of Bibfeldt in that campus’s life quite nearly cost Marty his hoped-for appointment as a Lutheran pastor. If Bruce Lincoln is correct that irreverence is a scholarly virtue, it was not recognized as such at Concordia Seminary. Happily, when Marty joined the faculty at the University of Chicago Divinity School (after serving as a Lutheran minister and completing his Ph.D.), Bibfeldt decided to come with him and was reborn in Swift Hall, where he has enjoyed an appropriately intermittent, not to say checkered career over the last fifty years. Major books of Bibfeldt that have been discovered, by students and occasionally by faculty:

- Philemerbrief. Bibfeldt’s massive commentary on the Epistle to Philemon, a multi-volume treatise that devotes at least one paragraph to each word of the letter. It is the longest commentary in the history of biblical scholarship on the shortest letter in the canonical corpus.

- A Pragmatist’s Paraphrase of the Sayings of Jesus. Bibfeldt became an interdisciplinary scholar at Chicago, and his studies in the University’s Department of Economics prompted him to formulate what alumnus Joe Price described as a “Hermeneutic of Reversism” in which any saying of Jesus which is too hard to follow simply means the opposite of what it says. Not content to remain merely theoretical, Bibfeldt re-translated the Gospels accordingly. This too is a multi-volume work, but selections from the Sermon on the Mount will give a sense of how Bibfeldt applies it:

Matt 5:3: “Blessed are the rich in money, for they can build bigger and better churches. Who cares about the Kingdom of God?”, and

Matt 5:8: “Blessed are those whose external appearance and behavior is impeccable, for they shall look nice when they see God.”

- The Minister as Mortician. This single volume – a rare case of brevity in the corpus – collects Bibfeldt’s speculative essays on the future of pastoral care. (This is a notable case of collaborative scholarly detective work involving a number of Chicago alums, including Otto Dreydoppel, Katie Dvorak, and Janet Summers.) It is sorted into sections on care for the dead and for the living. Regarding the dead, Bibfeldt emphasized the liberties available to the counselor and was especially concerned with matters of ennui and depression. The essays on the living stood apart and subsequently were published in a separate volume, I’m Okay; You’re a Cretin, or a Slob.

- The Kierkegaard Volumes. Bibfeldt read Soren Kierkegaard’s Either/Or and immediately penned a rebuttal, also in two volumes, under the title Both/And. When, to Bibfeldt’s consternation, reviews were unfavorable, he offered his rebuttal in a second volume: Both/And And/Or Either/Or. It was also at this time that Bibfeldt constructed his coat of arms, which features Proteus rampant on a weathervane, and the phrase Ego saltare ad tune quod suus “played” as his motto –translated with feeling by former Dean David Nirenberg as “I dance to the tune that is played.”

Marty always held that, true to his origins, Bibfeldt shows his best self at moments when students judge that the time is ripe for his soon to be latest appearance. So, it was a halcyon occasion this past Friday when the officers of the Divinity Students Association, led by current president Izak Santana, announced a gathering to herald the return of Franz Bibfeldt to the Divinity School on Friday, April 1. To great approbation, Dean James T. Robinson announced that the School was redevoting all of its resources to the study of Bibfeldt. Reports on Bibfeldt’s failed proposals to the American Academy of Religion (Bradley Hanson), Bibfeldt’s just unsealed political correspondence, including a promise from former President Carter to award him the Congressional Medal of Freedom during his second term (Lydia Herndon), and his quixotic efforts to place his work on the internet (Mandy Burton), were followed by an extemporaneous rumination (Jean-Luc Marion) suggesting that the thorny theological dynamic of absence and presence might be best illuminated via comparison of Bibfeldt with historian of religions Wendy Doniger.

The evening’s sole discordant note occurred when Mr. Santana, apparently plagued by second thoughts about his initiative, asserted that everyone knows that Bibfeldt is not real. He was summarily booed and, following shouts of “heresy!” was removed immediately from the premises.

All of this activity, past and present, took place in the Divinity School Common Room, a communal space that was unoccupied during the Covid epidemic and where laughter is typically light and at most mildly ironic. Bibfeldt’s return invited the Common Room, and not incidentally all of us who occupied it, to remember viscerally that there is a place – perhaps an essential place – for the occasional fit of outright laughter in even the most scholarly house.