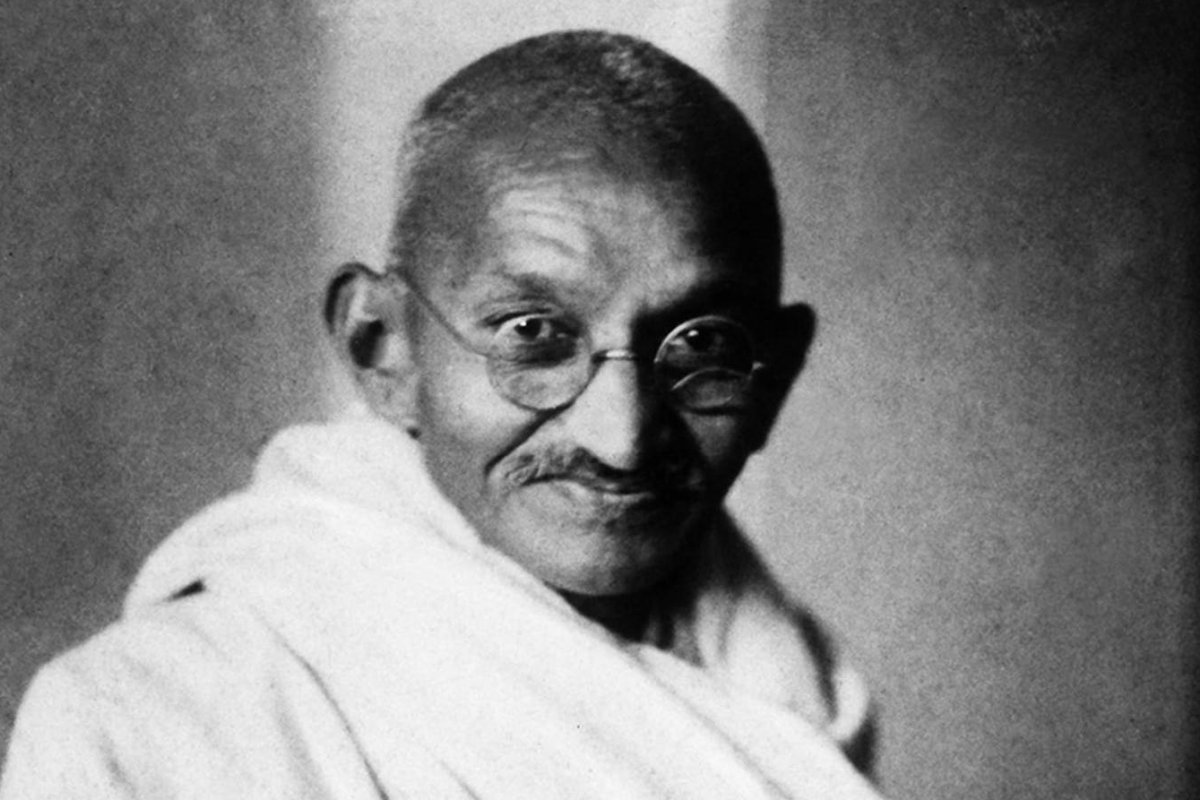

Remembering Gandhi in a Critical Age

Gandhi insisted on the power of each individual to contribute something to the realization of truth and freedom.

On the 150th anniversary of Mohandas Gandhi’s birth, let us take a moment to celebrate the great religious leader who won India’s independence from English colonial rule, who won the Nobel Peace Prize, and who said, “Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

Except ... none of those things are true. Or at least, not quite true. Gandhi played a major role in winning Indian independence, but the decisive factor was World War II and not Gandhi’s nonviolent campaigns. He never won the Nobel Peace Prize, though the Nobel Committee did withhold the prize in 1948 in his honor. And Gandhi never said those oft-quoted words, though the sentiment can be found throughout his writings and speeches.

By now, we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that the inspiring story we were told growing up was oversimplified and that what we thought we knew turned out to be false. In the cultural moment in which we live, it has become common to be told that one person’s actions are insignificant in the face of global problems, to discover that the people we put on pedestals do not belong there, and to treat with suspicion everything we read on the internet.

We are living in a critical age. This is not a bad thing. (To critique our culture for being overly critical would be ironic, to say the least.) Criticism is an essential part of making the world a better place. We need to challenge false assumptions, expose hidden injustices, and disrupt ossified ideologies if we are to bring about a more equitable, truthful society. Suspicion, doubt, and complexity—the dominant notes in the humanities and social sciences today—have inestimable value.

In order for positive social change to happen, though, the critical must be joined by the constructive. We need projects of imagination and recovery, resulting in positive courses of action and models for emulation. The critical and the constructive work together like a scalpel and stitches.

Unless accompanied by hope, trust, and a plan of action, criticism can all too easily lead to cynicism and despair. Without a constructive vision of a better world and steps that ordinary people can take to build it, criticism seems nihilistic. Some people refuse to take criticism seriously because they refuse to live in a world without heroes, without answers, and without dreams. Others double down on criticism, leading to the excesses of call-out culture on the left and the politics of distrust that has come to define the right. Others, convinced that global problems are too deeply rooted to be resolved, focus only on carving out a good life for themselves and those close to them. In this critical age, it can seem naïve to put one’s faith in anyone or anything, to insist that steps can be done to make things better, or to have confidence in our commitments.

At present, the critical has outpaced the constructive, and the constructive needs to catch up.

Gandhi is an ally in this effort. Though he is remembered for his acts of resistance, he reiterated that these were only part of his “Constructive Programme” for making India—and through India, the world—a more interdependent and equitable place. Gandhi’s “no” to British colonial rule was encompassed by a broader “yes” to a comprehensive vision of freedom he called purna swaraj and an abiding faith in the power of satya, truth-in-action.

Gandhi insisted on the power of each individual to contribute something to the realization of truth and freedom. In Gandhi’s ethics, we should ask of our actions not whether they are adequate to the problems we face, but whether our actions are the best we can do. This is how Gandhi interpreted the classical Hindu concept of varnashrama dharma: each person has a role to play and should concentrate their efforts on discovering and fulfilling that role. This outlook is only possible in the context of trust, whether trust in the divine or trust in a larger movement of other individuals fulfilling their roles. Gandhi’s reading of the Bhagavad Gita reinforced this conviction. A person finds the power to care for those in need, not by imagining that everything depends upon them, but by realizing in faith that it does not. Freed from the crushing weight of responsibility for the world, Gandhi maintained, a person is able be more active in working for the good.

Gandhi argued that compassionate action ripples out into the world, and that one should concentrate first on the local level. Global change begins with spiritual work on oneself and selfless work for those in one’s immediate community. It can be easy to see the small actions for peace in our everyday lives as insignificant in the shadow of chronic social crises, or worse as distractions from the real issues. Gandhi reminds us that these small acts are part and parcel of the overarching struggle for peace in the world. The cornerstone of Gandhi’s philosophy is that small actions taken by ordinary people—like spinning yarn at a wheel, wearing Indian-made cloth, and treating marginalized people with respect—are the very building blocks of revolutionary social change.

The path to a better world always has a degree of uncertainty, and every proposed plan has its dangers and shortcomings. In a critical age, we are often reminded that the best-laid plans have unintended consequences, received wisdom is only half-true, and the traditions we rely on have unsettling histories. To prevent criticism from resulting in inertia, Gandhi emphasized the experimental nature of human action. “The golden rule is to act fearlessly upon what one believes to be right,” he said, adding that we should expect to make mistakes and learn from them (p.202). When one acts upon what one believes, criticism refines rather than hinders. “For that person who has the strength of spirit to act upon what seems certain to him,” Gandhi argued, “there is no such thing as defeat. If he goes on acting in that spirit, even his errors will be corrected in the course of time” (p.233).

Finally, Gandhi reminds us of the necessity of hope, even if a chastened hope. He wrote, “The law of love governs the world. Life persists in the face of death. The universe continues in spite of destruction incessantly going on. Truth triumphs over untruth. Love conquers hate” (p.173). In a critical age, this may sound naïve. But Gandhi’s life, flawed and limited though it is, stands as a testimony to the constructive, world-changing power of truth and love.

|

Author, Russell Johnson (PhD’19), is a Teaching Fellow at the University of Chicago. His research focuses on antagonism, nonviolence, and the philosophy of communication. He is currently teaching "Religion and the Nobel Peace Prize."

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School, with assistance from Nathan Hardy, a PhD Candidate in the History of Christianity at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.