A Recalcitrant Influence

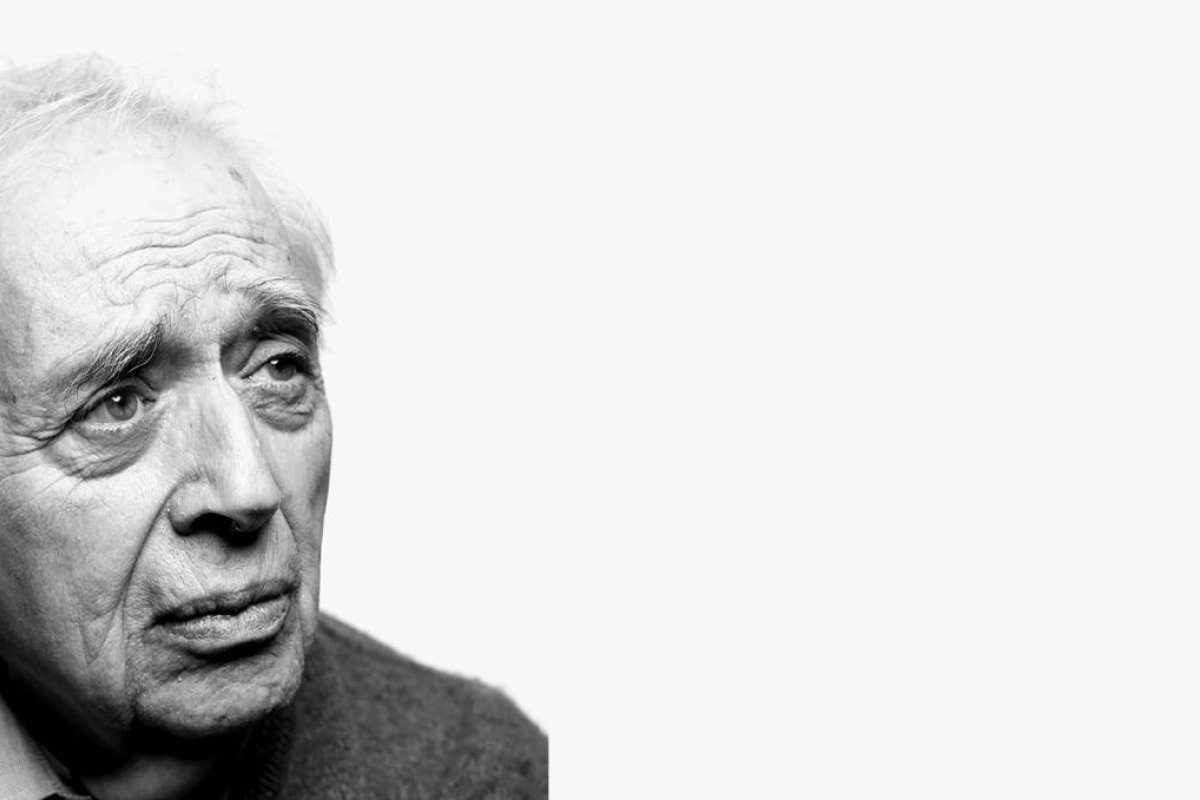

Matthew Creighton writes about the legacy of Harold Bloom

Last week the literary world bade adieu to Professor Harold Bloom, the most prodigious and well-known literary critic of the second half of the twentieth century. Looking back over approximately fifty years of writing, we conclude that one of the recursive and unifying features of his extensive output is the insistence upon regarding sacred works as rhetorical products, along with the attunement to the theological dimensions of imaginative fiction. In creating a model of how to construe the relationship between religion and literature as modes of cultural activity, Bloom fused the insights of two formidable precursors. From the minister-cum-scholar Northrop Frye, he began to view the totality of literary creation as an organic and interconnected whole, a “great code” founded on and decipherable with the aid of Scripture. From M.H. Abrams, his undergraduate adviser at Cornell, he learned not just that poets too were preoccupied with spiritual concerns, but that every instance of poetic communication necessarily involves four components: author, text, world, and audience.

Nevertheless, we can also speak of three discrete stages of Bloom’s criticism. The first is crystallized in the oft-misunderstood book The Anxiety of Influence (1973), in which he used Freudian psychoanalysis as a method for understanding the dynamics of artistic creation. In essence, he argued that one could trace a common process whereby young poets rebel against the literary forbearers that simultaneously and paradoxically shape and nourish their artistic sensibilities, in order to carve out a space for their own originality and yearning for greatness. Such indebtedness produces not encouragement but anxiety because the poet has to overcome the fear that he is all too late to the game, that he has no contribution of his own to make because it’s all been said already. The third stage, built on the project undertaken in the second, is marked by both a broadening of subject matter, and a move away from writing intended for the academy and towards a more general readership—if by “general” he meant an audience who was as well-read and well-versed as he was, and less interested in the strain of elucidating works of literature than in desultory, labyrinthine musings about them.

Yet it is the second period for which Bloom will be most remembered—either with regard or with disdain—its tendentiousness the fulcrum on which his legacy has been and will continue to be appraised.

Using a term from religious contexts that refers to the selection and consolidation of sacred texts deemed authoritative, Bloom pointed to a “canon” of Western literature that stands at the apex of human artistic endeavor, a treasury of great works whose inclusion is secured on the basis of their aesthetic value. The argument for the existence of and necessity for a canon was underlaid by the presupposition that not all art is created equal or is worthy of equitable consideration. Yet Bloom also insisted that the demand to be discriminating and exercise judiciousness in matters of taste derived from the limitations of the human estate. In other words, canons would be unnecessary if we lived forever; it is our mortality that pressures us to choose the best.

The pantheon Bloom erected wonderfully confirmed the bias of the antagonists he had in mind while constructing it. The canon had come to be regarded by many on the left as “an instrument of cultural, hence political, hegemony—as a subtle fraud devised by dead white males to reinforce ethnic and sexist oppression.” No small wonder for Bloom’s opponents, then, that his canon was comprised exclusively of white males. Seeking to expose power wherever they could find it and guided by a spirit of democratic leveling, these critics called not only for the incorporation of hitherto “oppressed” voices, but also for a fundamental rethinking of the criteria of aesthetic merit along more superficial conceptions of identity. Bloom deplored this shift in outlook because he thought that it sacrificed the recognition of artistic achievement for political sensitivity. Judging from the range of books and authors that he came to cherish, these cultured despisers overlook that a canon can include as much as exclude, can be dynamic and flexible instead of fixed and static, and that diversity will be achieved naturally rather than artificially if one really reads far and wide. Yet even without this expanded canopy, to see the canonized simply as “white” males is not merely an inaccurate and inadequate description of their identity as human beings—it altogether belittles their singular contributions in and to the realm of the imagination.

The “canon wars” of the 1980s and 90s in which Bloom was embroiled have their roots in the dual rise of multiculturalism and identity politics, movements extending back to the 1960s that rapidly permeated the halls and hearts of the academic and non-academic literary worlds. But in a very real sense, Bloom has never been more relevant than the current moment. Increasingly our gaze is but skin deep, and individuals more and more are reduced to the group(s) to which they belong—cultural trends that are correlated to elusive but no doubt prevalent prejudices inside and outside the academy concerning the nature, valuation, and purpose of art. For many on the progressive left, two aesthetic assumptions have risen to axiomatic status. The first assumption is that “[P]ersonal identity plus political position equals aesthetic value,” that “a good work of art is made of good politics and that good politics is a matter of identity.” Often this suspect estimation takes the form of white=bad, non-white=good. The related and equally dubious proposition is that the function of art is to “empower” historically marginalized groups and, by acknowledging their status as outsiders, begin to redress it. One can register the pervasive grasp of this claim in the move in the implied usage of “representation” away from the mimetic and towards its socio-political connotation, both in terms of inclusivity as well as of the artist who projects himself as standing in and speaking for the voiceless collective.

What unites these assumptions is their evasion of aesthetic content, of privileging accidents of birth over accomplishment. With Bloom’s passing we have lost one of the most impassioned challenges to this dramatic shift. He never pretended to have discovered a universal standard for beauty—only to advance the notion that elevating literary giants also enhances our own lives. There are many who, for the reasons adumbrated above, impatiently waited to bid him adieu, and the hyperactivity of the twenty-four-hour news cycle certainly expedites their wishful forgetting. But Bloom’s stance touches on some of our most pressing national questions about identity, unity, and merit, thus bearing serious implications beyond tastefulness.

Editor's Note: As with every Sightings column, the views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editors. That said, we would be remiss to publish this piece without noting that Harold Bloom was not only a polarizing figure for his scholarly contributions—especially for his argument for a “Western Canon,” as noted in the column above—but also that his legacy is a complicated one, not least because of credible allegations of sexual harassment that have been made against him. We encourage readers to consider this essay as the beginning of a conversation about Bloom’s legacy, and we invite you to share your thoughts with us.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School, with assistance from Nathan Hardy, a PhD Candidate in the History of Christianity at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.