Questions in a Nuclear Age

Editor’s Note: Sightings will be on “holiday hiatus” until Thursday, January 4

Editor’s Note: Sightings will be on “holiday hiatus” until Thursday, January 4. We would like to thank our readers and contributors for their continued support and engagement this past year, and we look forward to bringing you more of the very best commentary on religion in public life during the year ahead.

How should we use our power? When is violence justified?

How should we use our power? When is violence justified?

In my role as a parent to three children, such questions come up regularly. When my children were younger, these revolved around how to carry themselves when faced with threats of violence on the playground. “If a guy is about to hit me,” one of my sons might ask, “can I hit him first?” “If I see someone picking on another person,” another would ask, “how should I stop it?” In our family, as I imagine in many, these questions are grounded in an ethical sensibility informed by our religious tradition.

With the world standing closer to nuclear confrontation than it has seemingly been in decades, my children are asking new questions—which are variations on these smaller-scale rehearsals. “If North Korea is going to attack the United States with nuclear weapons,” they have asked, “shouldn’t the U.S. hit them first?”

Inherent in these comparisons is a tension: how far can we extend moral and ethical considerations from discourses about interpersonal conflicts or even Just War theory before we are forced to contemplate aspects that make nuclear war qualitatively different from a playground brawl?

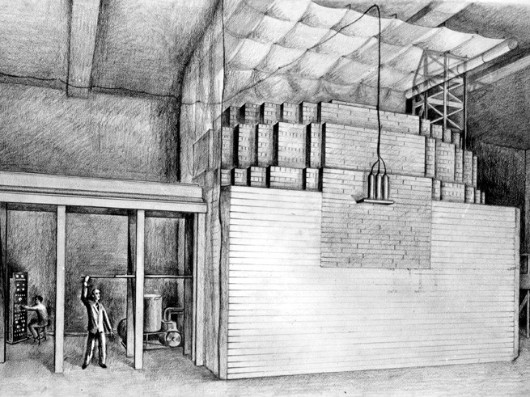

These aren’t new questions, of course. They have been asked since at least the first successful atomic chain reaction, conducted in Hyde Park seventy-five years ago. Here are two examples.

In the spring of 1948, less than three years after the dawn of the atomic age, Archbishop Richard J. Cushing of Boston addressed the clergy under his charge. “There are two possible approaches to the world,” Cushing told the group. “The one is dominantly, if not exclusively materialist; the other is essentially spiritual. The materialist pyramid has reached its apex in the atomic bomb. That theory has uttered its last word of Power—and has produced its ultimate reaction: Fear.”

In this early religious response to the realities of atomic power, Cushing, who would go on to officiate at both the wedding and funeral of John F. Kennedy, drew on well-worn categories. At root, according to Cushing, the challenges of the atomic era weren’t fundamentally different than the ancient tension between the material and the spiritual. “We have to choose between the dominance of material Power or that of Spiritual Values,” he said. While the atomic bomb created a difference in the degree of material power available, the basic questions it posed were the same as those faced by Cain: how should we use our power?

Other religious leaders saw things differently. While of course some basic questions are the same whether one is talking about a fistfight or thermonuclear war, it’s also obvious that something is different. Writing in 1981, John C. Bennett, a former president of Union Theological Seminary and leading civil rights and antiwar activist, highlighted one aspect of this discontinuity. Catholic Just War theory includes the concept of a “double effect” which recognizes that noncombatants can wind up as victims of even legitimate military strikes, Bennett reflected. This consideration leads to the notion of proportionality in Just War theory: a military strike must account for the noncombatants who might be harmed, and must make serious efforts to limit such casualties.

Nevertheless, Bennett observed, “when the side effect consists of 10 million to 20 million casualties, many of them noncombatants, there is no possibility of justifying the action.” In addition, Bennett reminded his readers, “nuclear war would produce many indirect or delayed side effects which have never entered into the traditional discussion of the ‘just’ and ‘unjust’ war.”

How do the responses of Cushing and Bennett help me frame the discussion for my children? Bennett’s approach strikes me as sober and realistic, acknowledging the unique destructive capacity of nuclear weapons while attempting to draw on Catholic Just War teaching. Combined with the thought of realists like Reinhold Niebuhr, it can help us maintain a moral vision of eradicating nuclear weapons along with war altogether, while also operating in the world as it is.

At the same time, what is new in the current discussion, and seemingly unaccounted for by the historical examples of previous public discussion, is the notion that nuclear weapons could be wielded by less-than-rational actors. What happens when impulsive, irrational leaders wield unchecked authority to carry out first-strike nuclear attacks? Previous theories have rested on the notion that mutual assured destruction would prevent a nuclear war. In the current war of words between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un, that notion seems downright quaint.

And that brings me back to Cardinal Cushing and his emphasis on the basic continuity of the questions of moral formation, whether we’re talking about a schoolyard scrap or an international nuclear crisis. In a later passage in the same talk, Cushing laid out his charge to his parish priests: “The production of saints is the principal contribution the Church can make to the redemption of society,” he said. “No age has ever needed saints in every walk of life as does this Atomic Age. Only saints can be trusted with secrets potentially so disastrous!”

As a parent and a citizen, I can’t possibly disagree.

Resources

- Bennett, John C. “Countering the Theory of Limited Nuclear War.” The Christian Century. January 7-14, 1981.

- Cushing, Richard J. “A Spiritual Approach to the Atomic Age.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Vol. 4, No. 7 (June 1948): 222-224.

Image: Drawing of the atomic pile erected beneath the west stands of the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field. With this, a group of scientists achieved the first self-sustaining chain reaction, a controlled release of nuclear energy, on December 2, 1942. | Credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf2-00503], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Author, Joshua Feigelson, is Dean of Students at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Author, Joshua Feigelson, is Dean of Students at the University of Chicago Divinity School. |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco (AB’07, MDiv’10), a PhD candidate in Religion, Literature, and Visual Culture at the University of Chicago Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.