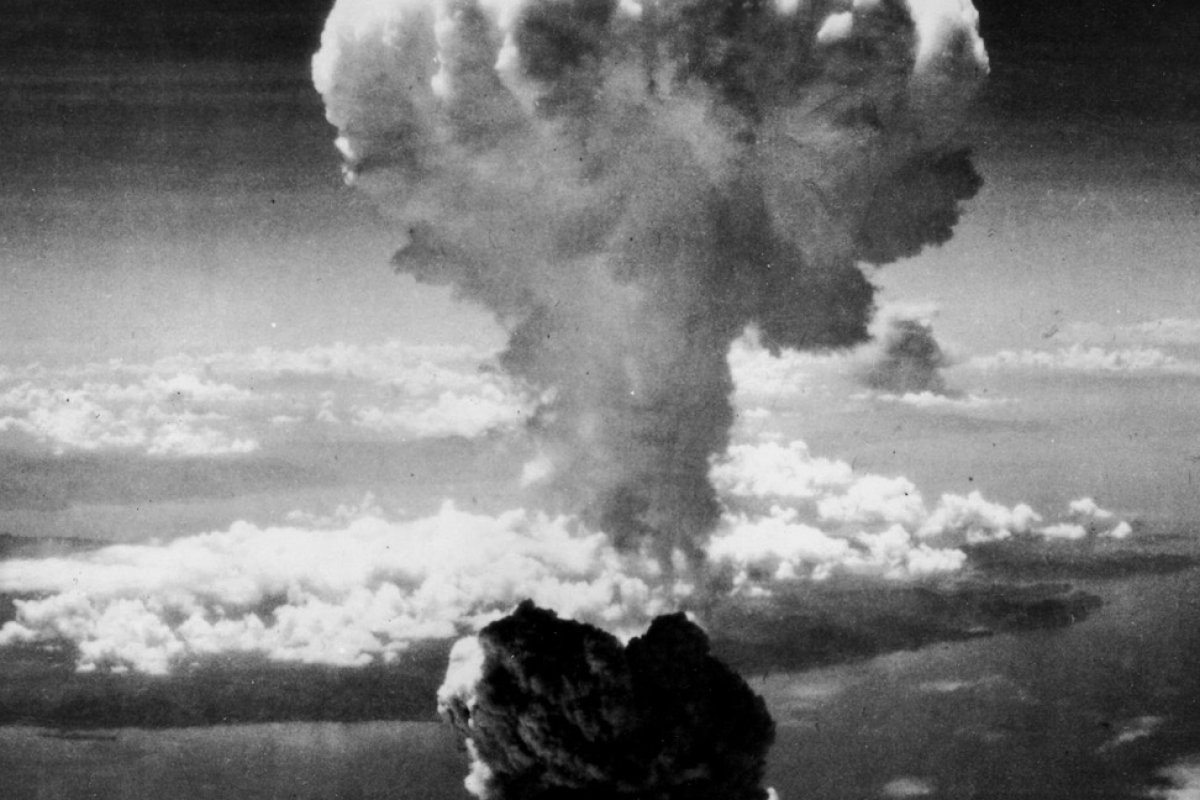

Moral Reckoning Under a Mushroom Cloud

How the upcoming 75th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki might help us better understand and address some of today's most pressing moral dilemmas

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima, Japan. Nagasaki was similarly bombed three days later. The Hiroshima death toll, immediate or in the bombing’s wake, reached 140,000—fewer than the current coronavirus death count in the United States, but more terrifying in detail. With so much already on our divided minds—the pandemic, financial devastation for many, racism and policing, school openings (or not), and more—it may seem too much to think back on what took place seventy-five years ago in Japan. Still, it can be a moment of needed learning and even grace.

If Chicago is not now one of the epicenters for the pandemic, the city, including the university in Hyde Park that bears its name, could (and probably should) be an epicenter for what some call a “reckoning,” or what Socrates called “the examined life,” as we approach this year’s anniversary of the bombing. The examination will be difficult, but, fortunately, it is “open book.” If we read the signs of the times and reread the past with humility and honesty, if we read or listen carefully to the words of others, we may find answers or at least clues regarding meanings, values, and actions—religious and otherwise—fit for troubled times and the days ahead.

On December 2, 1942, under the bleachers of the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field, where the “Monsters of the Midway” had played, Enrico Fermi and his Manhattan Project team were building a monster of another kind. The first self-sustained nuclear reaction that day was a crucial step. Geographical proximity does not determine identity, but as we approach this 75th anniversary of Hiroshima with racial reckoning on our minds, it may aid our reflection to note that the Henry Moore commemorative sculpture, near East 57th and Ellis, is much closer to one-time redlined neighborhoods, food deserts, and the street where Laquan McDonald was struck down than it is to the fabled Fermilab. On the other hand, the Barack Obama Presidential Center may soon be nearby, an open book on community organizing, constitutional law, relations between races and nations, and more.

But Chicago geography aside, race, racism, and Hiroshima may not be far apart. We cannot say for certain just what tipped the balance in President Truman’s mind towards his morally questionable decision to drop the bomb. Military leaders such as General Eisenhower did not think the bombing was necessary to end the war, and some involved in the Manhattan Project itself had grave moral misgivings about this new terrible weapon. But in this moment of racial reckoning, we might at least reconsider historian and ethnographer Ronald Takaki’s argument, some twenty-five years ago, that Truman’s racism, shared with others and extending to the Japanese (recall the internment camps), likely contributed to a decision on which Truman never looked back—even if we are called upon today to do just that. We might note, too, with reference to today, that, for Takaki, Truman’s wanting to appear “manly,” and not weak, might also have played a role.

But racism and other closely related biases cannot be the sole topic of our reckoning. Especially at this moment, the role of science also requires examination. Peter Parker, bitten by a radioactive spider, is not the only one to have understood that “with great power comes great responsibility.” Whether scientists have always done the responsible thing is not so certain. Indestructible plastics now clutter the seas, and the opioid crisis makes us wonder if, sometimes at least, scientists, or at least their employers, have been breaking bad. Years before Hiroshima, Nobel Prize-winning German chemist Fritz Haber did wonders with nitrogen-based fertilizers but also put his genius to work on gas warfare. “In times of peace, humanity; in times of war, the Fatherland,” was Haber’s point of view—the sort of conviction that, in the words of Richard Rhodes, contributed to “the long grave, already dug” that received the dead of World War I and of the years leading up to Hiroshima. Haber’s convictions drove his chemist-wife to suicide, and his poison gas led the soldier-poet Wilfred Owen to lament “the old lie” told to British schoolboys: “Dulche et decorum est pro patria mori” (“It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”)—a piece of poetry, incidentally, that presses the need in education for the humanities to help ensure that the sciences are humane.

With the mixed morals of science or scientists in mind, it is no wonder that Rhodes uses, as an epigraph for The Making of the Atomic Bomb, words from J. Robert Oppenheimer: “Taken as a story of human achievement and human blindness, the discoveries in the sciences are among the great epics.” The death and suffering of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were indeed epic in this sense. As for Oppenheimer with his pacifist leanings, scholars of religion may still ponder just why Donne’s poems so moved him to call the bomb’s testing “Trinity,” or why his reading of the Bhagavad Gita, joined to a notion of “complementarity” whereby a terrible weapon could both destroy and save, could lead him to justify development and then use of the bomb. After all, Mahatma Gandhi read the Gita, too. Maybe scholars of hermeneutics can sort things out and place their answers on Japanese graves.

Having witnessed the hell of Hiroshima, made possible by their genius, and taking due responsibility, some thoughtful people established in Chicago the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in 1945. The Bulletin’s Doomsday Clock has warned since then of disaster if we do not get our collective act together. The nuclear threat, climate change, and disruptive technologies have moved the clock’s hands ever closer to midnight in recent years. Especially pernicious and apparent now, the Bulletin warns, is a “new abnormal” of attacks on facts and the notion of truth itself that makes wicked problems even more difficult to address. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel put it with regard to the topic much on our minds, “You cannot fight the pandemic with lies and disinformation any more than you can fight it with hate or incitement to hatred. The limits of populism and denial of basic truths are being laid bare.” “Science is Truth,” Dr. Anthony Fauci has said, though always only with careful caveats about what science can and cannot know and do. Religion, with its truths, might do well to follow his bold-yet-humble-and-circumspect example.

The characters in the book open to us for answers to the test that Socrates proposed are many. Some are local; some, like the late John Lewis, may not be so near; and some, like fossil fuel tycoon John D. Rockefeller, who put divinity at the center of a great university with its many Nobel Laureates in science and economics, may be more problematic and difficult to parse.

In any event, as August 6 approaches, with all its messages about war and peace and human relations gone horribly wrong, I suggest we look for guidance to a teenaged marine (sent packing for lying about his age), then sailor and soldier, a high school dropout who became a college professor and later the nation’s longest-serving majority leader in the U.S. Senate. Early in Mike Mansfield’s term as ambassador to Japan, a U.S. Navy nuclear submarine surfaced in violation of international law and ended up sinking a Japanese fishing boat that resulted in loss of life. With cameras rolling at his insistence, Mansfield personally delivered to the emperor a note of apology, with a deep below-the-waist bow. I cannot help but think that this humble and principled man, who once taught Asian history to college students in Montana, and later opposed the Vietnam war, was apologizing, too, for taking lives that mattered in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Even if unintended, I think Mansfield was offering America and the world a free lesson in the examined life. A leader with strong religious convictions who did not trumpet his religion, perhaps he was also witnessing to that about which America’s first black president and those attending George Floyd’s funeral sang: the “Amazing Grace” that, little by little, can change human hearts and behavior, even of the slaver-“wretch” who wrote the hymn. Those adept at “sightings” may discern that very grace at work all around us, even today. But Mansfield’s brief-but-deep act of contrition, on behalf of a nuclear power like no other, may also be a stern warning that if some amazing grace is to save us, or even buy us time, that same grace will not in any sense be cheap.

References

“A new abnormal: It is still 2 minutes to midnight,” Doomsday Clock, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/.

James A. Hijiya, “The Gita of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 144/2 (June 200): 123-167.

Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, 25th Anniversary Edition, with new forward by Richard Rhodes (New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1986; 2012).

Ronald Takaki, Hiroshima: Why America Dropped the Bomb (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1995).

Images: Feature: A photo of the mushroom cloud over Nagasaki, August 6, 1945, taken by Charles Levy from one of the B-29 Superfortresses used in the attack. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Archives); Second: The remnants of a building destroyed by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.