Monuments, Memorials, and the Resacralization of Space

The landscape of public space shapes collective understandings of the past

Identity is relational. Who and what we are depends on those surrounding us, a mix of our interactions with our alrededores/environments, with new and old narratives. Identity is multilayered, stretching in all directions, from past to present, vertically and horizontally, chronologically and spatially.

-Gloria Anzaldúa, Light In The Dark/Luz En Lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality

During the summer of 2020, I received a grant from UNC-Chapel Hill’s Center for the Study of the American South to visit sites around the South where the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) has worked with local communities to raise awareness of lynchings that took place during the 19th and 20th centuries. Their work takes several forms: the raising of a historical marker that tells both a local and national history of white violence; research into, and organization of, a memorial ceremony for the victim, commemorating what is known of their life and their death; and identification and collection of soil from the site where the lynching took place, the soil acting as both witness and representation of violence and victim.

Collecting soil and raising historical markers gives physical representation to concealed histories of violence that are often absent from mainstream understandings of what the United States is and how it came to be. EJI works to change the visible histories of towns and cities, to transform and reshape the visual history of the landscapes we inherit and inhabit. Their work—which includes the Community Remembrance Project, the Legacy Museum and Peace and Justice Memorial in Montgomery, and efforts to reform America’s racist criminal justice system—brings together fractured histories of white violence and subjugation and Black suffering and endurance in order to reckon with an incomplete and deceptive story of America.

If, as suggested by Katherine McKittrick, we can understand domination as a visible, spatial project in which power seeks to cement itself as static and unchanging, a process that involves the concealment and erasure of subaltern counternarratives, we can then see the work of the EJI (and the communities they support) as a challenge to dominating white narratives of history. It is one part of the broader, ongoing work to challenge the normative histories, symbols, and mythologies that claim sacred and foundational status.

It is difficult to challenge the present through a reckoning with the past. We have seen this in Trump’s 1776 Commission and his condemnation of “angry mobs” attacking the “sacred memorials” and “treasured legacies” of the nation; in his statement that protests against police brutality and anti-Black racism were part of “a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values, and indoctrinate our children”; and in the Confederate flags carried inside the US Capitol on January 6th, 2021. The American sacred—a blurring of whiteness, Christianity, and American nationalism—remains a force to be reckoned with.

What became apparent early on in my travels was that, often, these violent and racist local histories had not just been erased and obscured, but were often visibly replaced by the symbols and mythology of the Lost Cause, in the form of Confederate monuments and memorials.

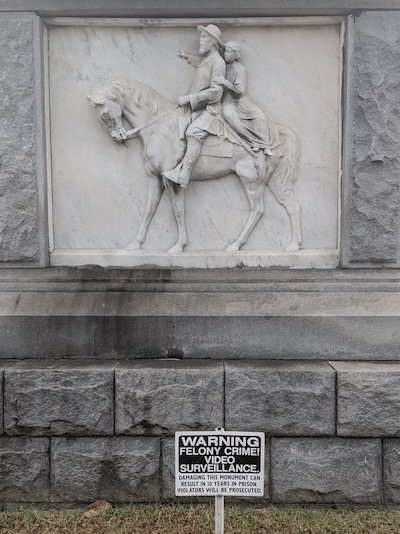

In Gadsden, Alabama, for instance, EJI worked with the city and local organizations to erect a historical marker in 2016 that detailed the lynching of Bunk Richardson on February 11, 1906. Richardson was murdered by a mob outraged that one of Richardson's Black friends, who was convicted of raping and murdering a white woman, had had his death sentence commuted to life in prison. The marker is located roughly 500 feet from a statue of Emma Sansom, a young white Alabama farm girl who is venerated for assisting Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest; this statue was erected in 1906, the same year that Richardson was lynched. When I visited in August of 2020, a sign in front of the statue warned that any attempt to damage the monument could result in extended imprisonment.

Similarly, in Charles City County, Virginia, the site where Isaac Brandon was lynched in 1892 was located a short distance downhill from the county courthouse, where a Confederate obelisk was erected in 1900. And in Abbeville, South Carolina, the “Birthplace and Deathbed of the Confederacy,” a historical marker placed in front of the town’s Opera House in 2016 recognized the 1916 lynching of Anthony Crawford and the expulsion of his family from the state after he cursed at a white man. The lynching occurred across the street from a large confederate obelisk in the center of downtown, erected in 1906 and replaced in 1996.

While these landscapes have recently been altered to commemorate the victims of lynching, EJI’s recovering and revealing this history forces us to contend with difficult questions. What did it mean to visit these spaces before a historical marker acknowledging the lynching was erected, when the only visible monument was dedicated to the Confederacy? What did it mean for those who knew this erased history and experienced its silence? What was it to see murder and monument juxtaposed with one another – the absent presence of Black death and white violence, the physical presence of white narrative and control?

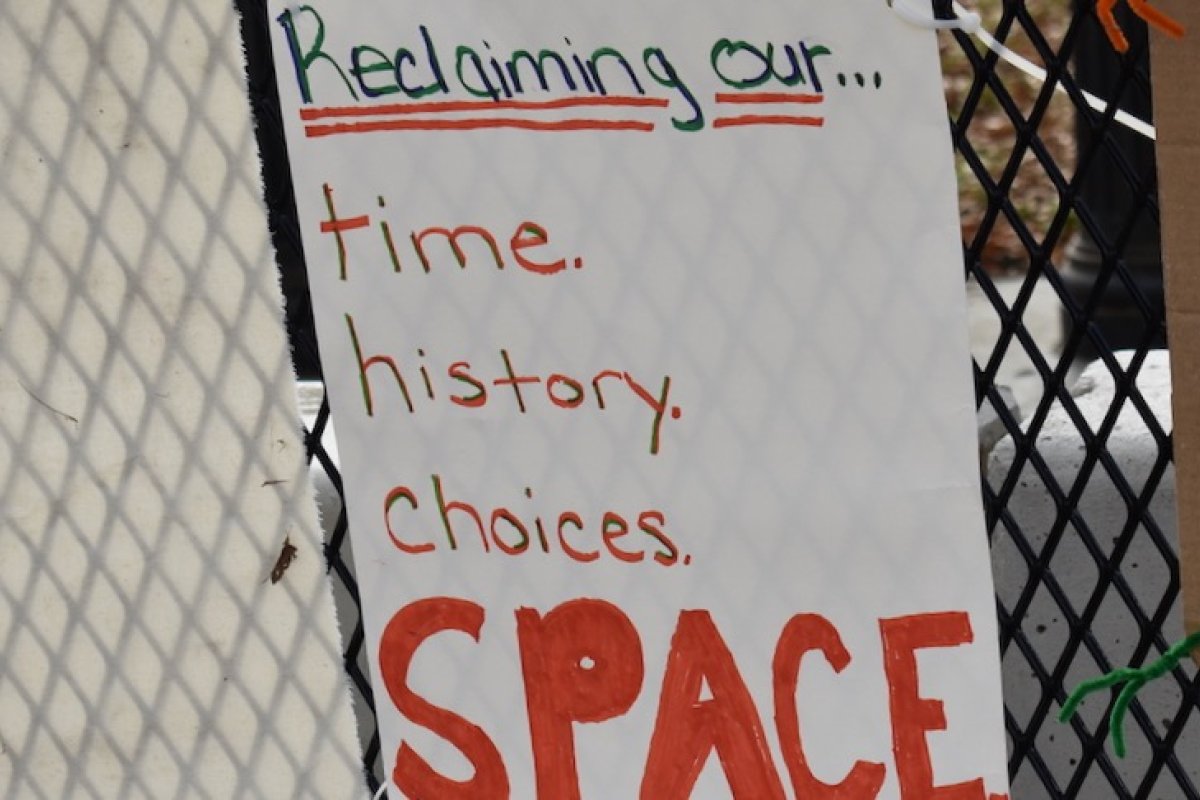

There are consequences that come with denying and fragmenting the histories of white violence that have brought us to this point; January 6th, 2021 was one of these consequences. But I would argue we are also in a moment of expanded historical contestation and reclamation. These re-narrations of local and national histories were not solely confined to historical markers; they could be seen in many aspects of the 2020 protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. Throughout the South, those who recognized the continued racial injustice marring the American landscape made sure that this was not only highlighted, but that its broader lineage could be explicitly perceived.

In Richmond, Monument Avenue continues to be transformed, reclaimed, and dismantled by locals who condemn the continued veneration of the confederacy. In Alexandria, protestors had attached signs saying “A MAN WAS LYNCHED BY THE POLICE. WHAT ARE YOU DOING ABOUT IT?” to city signs near the lynching sites of Joseph McCoy (†1897) and Benjamin Thomas (†1899); up the hill, the Confederate monument installed on Washington Parkway in 1899 had been removed in early June of 2020, leaving only an empty pedestal. And in Louisville, down the street from another empty pedestal, Highland Baptist Church filled their front yard with crosses bearing the names of victims of police violence.

How we move through and understand space and place informs our sense of right and wrong, of worth and worthlessness, of what histories we should recognize and respond to. We form our individual and collective identities through what we see and experience, what we remember and pass on, what we forget or deny, what histories are excavated or remain buried. History, space, and soil are never neutral, and it is up to each of us to unearth the past and cultivate transformative futures.

Images: Feature: One of countless signs attached to the fencing around Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C., after the 2020 presidential election was called for Joe Biden. (Photo by author, 18 November 2020) Second: A sign at the base of the Emma Samson Confederate monument in Gadsden, AL, warns against defacement. (Photo by author, 3 August 2020) Third: Highland Baptist Church in Louisville, KY, placed over 100 crosses on its lawn mourning Black people killed by police in the US. (Photo by author, 27 June 2020)

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.