Martin Buber’s Hope in Polarized Times

The important lesson a midcentury speech by the Jewish philosopher holds for “this hour”

A major news story of the last year—or rather, a recurring theme among many news stories—is the rising tide of polarization in U.S. politics.

Polarization should not be confused with disagreement. Disagreement, even to the point of disruptive protest, has been a vital part of American political culture for centuries. Democracies thrive on healthy conflict, the voicing of disparate opinions, and struggles to discern the most just and equitable policies. In a room of one hundred people who disagree, you might hear a hundred different viewpoints, but people can understand each other and hash out their differences.

Polarization, by contrast, occurs when people with differing viewpoints coalesce into two mutually opposed groups. As a society becomes more polarized, these groups become increasingly suspicious of one another. The diversity of viewpoints gets condensed into a simplified “us versus them,” and the pressure to defeat “them” fosters greater homogeneity on each side. In a room with one hundred people who are polarized, you’ll hear only two viewpoints, expressed antagonistically by groups who can’t stand one another.

Polls show that hostility and suspicion between Republicans and Democrats are much higher than in recent memory. However, this situation is far from unprecedented, and we may find insight and hope from how past luminaries analyzed polarization in their time. Now, as so often, the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber offers words of wisdom. In a rarely discussed speech, Buber gives an analysis of widespread distrust that speaks to the contemporary cultural-political divide.

At Carnegie Hall in 1952, Buber gave a lecture titled “Hope for this Hour.” His goal was to give an honest assessment of life during the escalating Cold War. He announced, “The human world is today, as never before, split into two camps, each of which understand the other as the embodiment of falsehood and itself as the embodiment of truth.” Buber does not advocate a centrist position between these two camps, nor does he here weigh in on the disputed points between them. Rather, Buber analyzes how this disagreement over economic philosophies is a site of polarization. He makes three points that are relevant for “this hour” in our social landscape.

First, we need to be critical of the way disagreements are framed. In polarization, Buber says, a person is “more than ever inclined to see his own principle in its original purity and the opposing one in its present deterioration, especially if the forces of propaganda confirm his instincts in order to make better use of them.” He continues, “Expressed in modern terminology, he believes that he has ideas, his opponent only ideologies. This obsession feeds the mistrust that incites the two camps.” Put differently, polarization attenuates critical thinking, making us all too easily satisfied that our commitments are right because they are superior to those of our opponents. We also become less sensitive to distinctions and concerns of the other side, since we think we already know what really motivates their political behavior. Mistrust snowballs, then, as each side believes the other side is intentionally misrepresenting reality. The first thing we need in polarized times, Buber writes, is “criticism of our criticism.” Unless we hold ourselves to a high standard when inferring the motives and concerns of the other side, suspicion will get the better of truth.

Second, we need “individuation,” which means not treating the other side as a monolith but recognizing that each person has unique convictions. This idea is central to Buber’s philosophy of dialogue. One effect of polarization, he argues in “Hope for this Hour,” is the transformation of ordinary mistrust into “massive mistrust.” It is normal and even necessary to treat with suspicion the claims of a person who has shown themselves to be untrustworthy. We should be leery of an individual who has made a pattern of playing fast and loose with the truth. However, any transition from distrusting an unreliable individual to distrusting an opposing camp is not a change of degree but of kind. The other side’s speech becomes guilty until proven innocent. “One no longer merely fears that the other will voluntarily dissemble, but one simply takes it for granted that he cannot do otherwise.” Polarization is not extreme disagreement, but the erosion of the conditions—like trust—necessary for working through disagreement.

The treatment Buber recommends for this metastasizing mistrust is seeing others as individuals and not simply as parts of a devious “them.” Overcoming this “massive mistrust” is especially difficult in today’s United States. On the one hand, conservative leaders have repeatedly cast doubt on the reliability of liberal media outlets. On the other hand, the current president is an individual who has given ample reason to be distrusted, and it’s hard for Democrats to separate sincere Republicans from the leader of their party. Still, studies show that if we approach people under the assumption we might be able to dialogue with them, we are more likely to foster mutual understanding. Seeing each person as more than just their political affiliation is a step toward healthy disagreement and change.

Third and finally, Buber argues that polarization threatens the pursuit of other political goods. Referring to the three watchwords of the French Revolution, “liberté, égalité, fraternité,” Buber insists that liberty and equality will not survive long in the absence of fraternity. “The abstractions freedom and equality,” Buber says, are held together “through the more concrete fraternity, for only if men feel themselves to be brothers can they partake of a genuine freedom from one another and a genuine equality with one another.” Extending Buber’s point, I would add that if people do not believe they can cooperate with one another to achieve their political goals, the more likely they will either become increasingly cynical and more willing to justify non-democratic uses of power. Naïvely overestimating the possibilities of brotherhood and cooperation is a legitimate concern, but cynically dismissing such possibilities becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Hope for this Hour” concludes, not with a hopeful note, but with a challenge. Citizens need to push back against the forces of polarization. The flames of resentment and mistrust are fanned by politicians and journalists who stand to gain from a divided society, but these tactics only work as long as ordinary people allow them to. As Buber states, “The hope for this hour depends upon the hopers themselves, upon ourselves.” ♦

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.

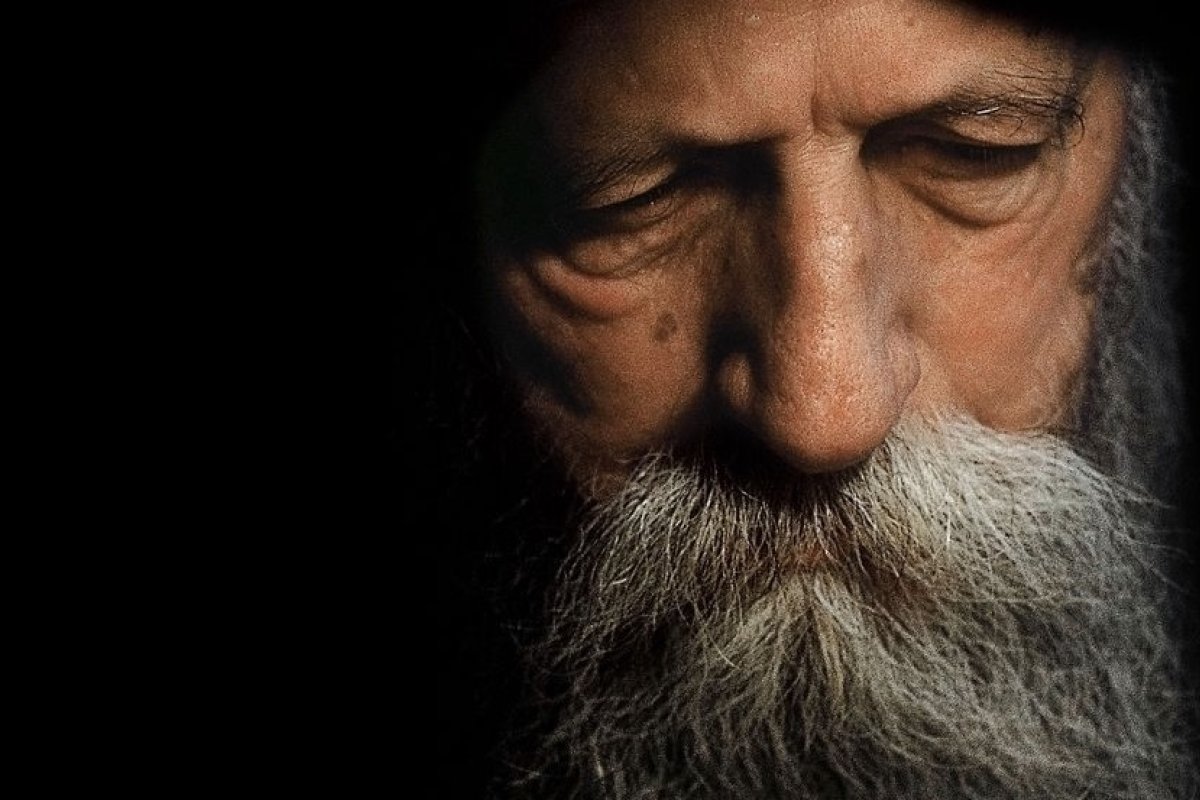

Image: Martin Buber in 1962. (Photo: Elliott Erwitt)