Labor Sunday

How American clergy in the 1920s turned from solidarity with workers to the mythology of the Good Christian Businessman

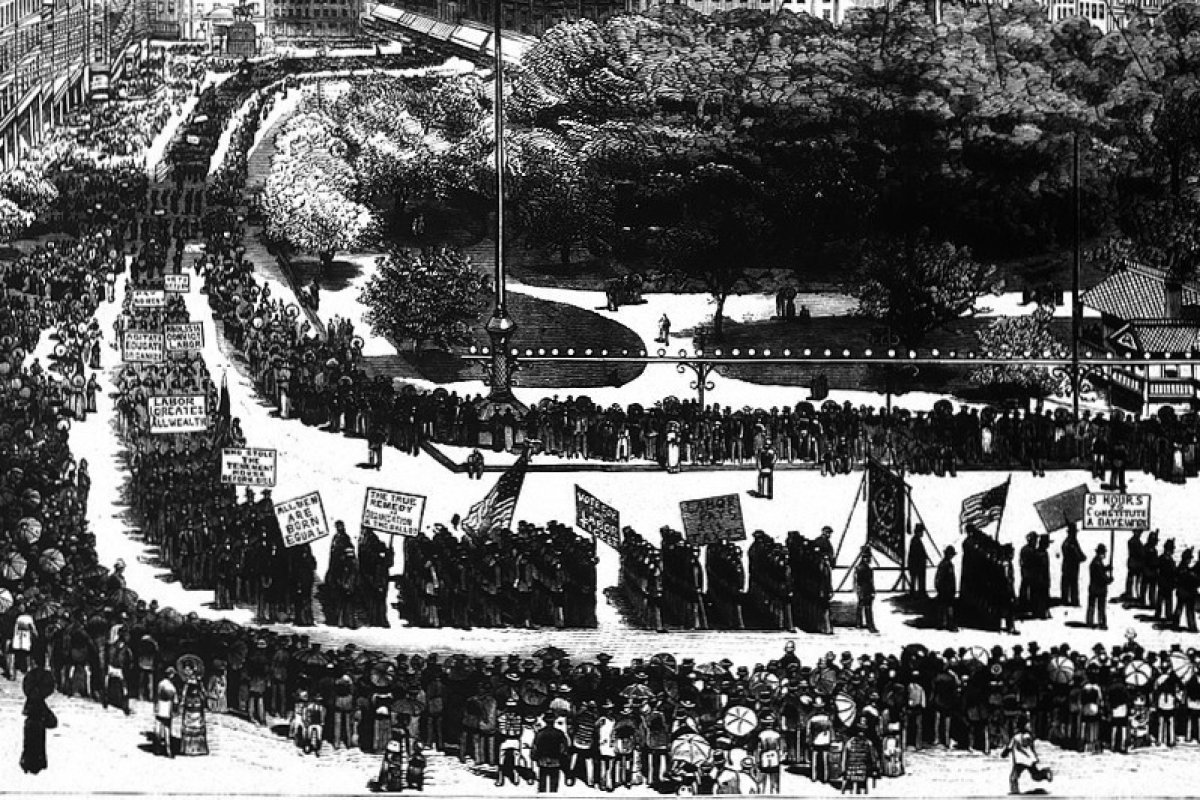

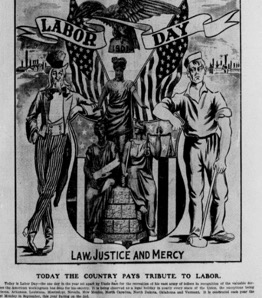

Imagine a trade union movement with so many active members that its “Labor Day” parades and celebrations shut down New York City for a day in 1882. Imagine a trade union movement so well-networked that, by 1894, more than two dozen states made the day an official holiday. Imagine a union movement so powerful that it compelled Protestant ministers across dozens of denominations to declare the Sunday before Labor Day as “Labor Sunday,” a day of meditation on the fact that Jesus was a Carpenter who preached the ethics of justice for all workers. Indeed, by 1909, both the American Federation of Labor and the Federal Council of Churches announced that this was an official part of the church calendar.

All these things are hard to imagine in 2020. The union movement is still alive, but most American clergy rarely talk about it. As nations around the world fight COVID-19 as a public health crisis, many are paying workers, as citizens, to stay home, even if that means collecting unemployment. In many European Union countries, citizens are invested as underwriters in the costs of national public health, so they are socially and financially incentivized to keep their neighbors healthy.

In the United States, we offered a rescue package directly to business owners, but very little aide has come to citizens for the role they play as citizens. The pandemic started with a one-time “Economic Impact Payment” to all American families with at least one member in the workforce. Full-time students and others who do not support themselves did not qualify for this aide. Subsequent federal investment in curtailing the economic effects of the virus, known as the CARES Act, has funded business owners with grants-in-aid of supplementary income. For example, the Paycheck Protection Program paid businesses to keep workers on the payroll who would otherwise be furloughed without pay. The CARES Act reimburses businesses for up to two weeks of “paid time off” for workers experiencing hardship directly related to the virus, including the necessity of caring for children and the elderly.

Of course, business owners have received these subsidies with the expectation that they pass on those funds to workers. But, when workers see that taxpayer money come into their hands in a check signed by their employer and delivered with a kind message from Human Resources, it very often appears as an expression of their employer’s generosity. At most, it is considered a short-term grant from the federal government, not a payment for acting as a good citizen and serving the public welfare.

This assumption that business owners know how to manage public funds better than their workers has a long history. Since at least the Gilded Age, American lawmakers have compelled citizens to entrust business owners as foremost American patriots. They have told workers to express their civic duty by working “faithfully,” without demanding “special treatment.” Since at least the 1910s, the renaissance of American welfare capitalism, business owners have resisted “labor legislation” with the argument that business owners know more about workers’ “real needs” than their union bosses. Maintaining this mythology of “good bosses” was central to “fighting” the perceived threats of socialism and, later, Communism. Celebrating the essential morality of American businessmen has been part of formal citizenship training in this country since the 1920s, and continues today. And, not surprisingly, American ministers played a critical role in creating and sustaining these messages.

If Labor Sunday was born of a strategic alliance between major Protestant denominations and the American Federation of Labor, the unmaking of Labor Sunday resulted from a new set of strategic alliances. After the First World War, the Federal Council of Churches, representing themselves as advocates for workers, boldly dismissed the claim that workers needed unions to thrive as people and experience social mobility. That year, John D. Rockefeller donated millions of dollars to the Federal Council to execute an anti-union campaign that celebrated the possibility of “Christian brotherhood” on the shop floor without “selfish” trade-union intermediaries. By 1921, Labor Sunday was still on the books, but the church holiday had largely become a day to reflect on the meaning, and hope, of good employers. The myth of “Christian businessmen” had become the Christian panacea for the perpetual inequalities of social class and workplace hierarchies.

Why did so many American Protestants adopt the view that unions were not necessary for industrial justice? Social Gospel ministers became enchanted with their own notoriety as mediators and nationally-recognized authorities on industrial relations. Charles Stelzle, the very same Presbyterian minister who invented “Labor Sunday,” spoke in his 1922 Labor Sunday sermon about all the things that foreboded a bright future for the American working classes. He reflected,

"There are… distinct signs of hope and progress in the industrial situation in America. There are earnest and courageous employers at work on constructive experiments. …The new role that is being played by the religious press in this connection is especially gratifying. And withal, the voice of the Church is being heard with unquestionably greater respect and influence." [1]

Stelzle recognized the many ways that business leaders broke their promises and relinquished their responsibilities to the public. But, he still trusted that business leaders could be persuaded, as Christian gentlemen, to treat their workers as Christian brothers and sisters. He expected that journalists could keep employers accountable to their promises. Stelzle was convinced that, as he put it, “the continued moral presence of the churches” would itself “complete the reformation” of American industrial relations.

A century later, we are suffering from a global recession. Millions of jobs have been cut, and many Americans struggle to access unemployment benefits. Yet, while church soup kitchens and food pantries have been busier than ever, most clergy have declined to offer commentary on the question of what unemployed workers deserve from their government. Official counts for unemployment are down this week, but the data is a bit more complicated. The official unemployment rate, after all, only measures those people who can prove that they were recently employed and are actively looking for new jobs. Meanwhile, American lawmakers chastise those who expect their federal unemployment checks to match their former income. It seems a distant memory to recall that unemployment benefits were instituted as an entitlement, and that the imperatives of a profit-system sometimes conflict with the imperatives of a national government. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin recently responded to the discussion on enhanced unemployment pay, “We’re not going to pay people more money to stay at home than work.” He suggested that it was ideal for unemployment benefits to only cover about 70% of one’s former paycheck in order to “incentivize” job hunting. It is evidently hard for most Americans, even American clergy, to imagine a federal government that entrusts their people with their own public funds. Rather, we continue to expect that the business community knows our “real needs” better than we do.

Looking back, it is easy to see that the strong labor unions of the early and mid- twentieth century served a critical role in educating the public, including both wage earners and ministers, on how businesses operate and what protections workers need and deserve. Without strong unions, not just workers, but clergy, too, can grow complacent in their ability to articulate the real needs of workers.

[1] Federal Council of Churches, Labor Sunday Message, 1922 (New York: Federal Council of Churches, [1922]), 8

Images: Feature: Illustration of the first American Labor Day Parade in New York City, on September 5, 1882, as it appeared in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 16 Sept. 1882. Second: "Law, Justice and Mercy," Deseret Evening News, 2 Sept. 1901. Third: Portrait of Charles Stelzle, Courtesy of University of Iowa Digital Archive.

Sightings is edited by Daniel Owings, a PhD Candidate in Theology at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Marty Center or its editor.