On Gods and Kings

How are we to “sight” the always intricate, sometimes chaotic, and too often hidden relationship between religious convictions and political order? More often than not it requires piecing together a jigsaw puzzle with hints from hither and yon, in both time and space

How are we to “sight” the always intricate, sometimes chaotic, and too often hidden relationship between religious convictions and political order? More often than not it requires piecing together a jigsaw puzzle with hints from hither and yon, in both time and space. What is at stake in this puzzle is precisely how best to understand not just the force of religion in political life, but also the decisions people must make about how to order their lives together. Today’s column is one such puzzle, and it concerns the ancient idea of kingship, which is not only woven into many religions, but that has, perhaps surprisingly, appeared again on our national stage.

How are we to “sight” the always intricate, sometimes chaotic, and too often hidden relationship between religious convictions and political order? More often than not it requires piecing together a jigsaw puzzle with hints from hither and yon, in both time and space. What is at stake in this puzzle is precisely how best to understand not just the force of religion in political life, but also the decisions people must make about how to order their lives together. Today’s column is one such puzzle, and it concerns the ancient idea of kingship, which is not only woven into many religions, but that has, perhaps surprisingly, appeared again on our national stage.Recently, a troubling saying—at least troubling to my mind—popped up on social media: “In Hell there is Democracy, in Heaven there is a Kingdom.” I find it troubling for a number of reasons, the most obvious being the post’s connection to the so-called “Trump Prophecy.” Sightings is of course animated by finding religion in unusual places, but, to be honest, the idea of the “Trump Prophecy” strikes me as more than just unusual, but in fact confusing if not oxymoronic. The term comes from a movie of that name that tells the story of a fireman, Mark Taylor, who received a message from God foretelling of Trump’s election years before it happened in 2016. It is this “hearing” of God, transformed into a “showing” of it in movie houses around the nation, that provoked this jigsaw puzzle of a Sightings column.

The idea of Trump as ordained by God to be president and to restore the nation’s morality is one piece in our political and religious puzzle. No less than Franklin Graham, among other prominent Evangelical leaders, has claimed that God intervened in the 2016 presidential election to Trump's benefit. More recently, the New York Times ran an opinion piece on December 31, 2018, by Katherine Stewart, titled “Why Trump Reigns as King Cyrus.” Stewart, critical of the "Trump Prophecy," explains for those initially confused—like myself—how some conservative Christians can believe the claim that, like King Cyrus of Persia, a non-Israelite who according to Isaiah 45 enabled the Jews to return from Babylonian captivity and restore the Temple in Jerusalem, Trump is likewise ordained by God to return our nation to righteousness. So ancient ideas of kingship return with the force of the repressed. And the focus is on the idea of kingship, not just on Trump himself. These believers admit the failings of Trump—remember, Cyrus was a non-Israelite—and see his failings even as signs that God is at work in him. Presumably, this is why the saying about the “hell of democracy” and the “kingdom in heaven” showed up in my social media.

Another piece of the puzzle: compressed into this single provocative quotation is not only an entire political theory and political theology (more on this in a moment), but it is also a snapshot of trends in American religiosity that challenge the sovereignty of “we the people” in favor of a divinely-appointed king. This is particularly baffling in a nation founded on the rejection of kings and queens, a rejection often enough driven by religious convictions. So what are we to make of it all? Several other pieces of the puzzle are needed.

One of the needed pieces is textual in character while the others are conceptual. Textually speaking, the actual quotation owes its origin to Saint John of Kronstadt of the Russian Orthodox Church (1829-1908). Aside from his veneration as a saint, Kronstadt was a monarchist, anti-communist, and, sadly, anti-semitic. But it is not the man or the saint that matters here. What gains pertinence is the use of his provocative saying, one that, as Evangelicals clearly know, warrants kingship by appeal to the Bible and ancient monarchical polities, and, in truth, is a political outlook at drastic odds with a democratic system. One could, then, search the biblical texts for insights into the kinds of kings ordained by God, say David in comparison to Cyrus and so on, a project which is admittedly beyond the scope of this column. But in doing so one would inevitably confront conceptual pieces to the puzzle.

Anthropologists—like David Graeber and Marshall Sahlins, in their massive study, On Kings (2017)—and sociologists—most recently in Robert Bellah’s equally massive Religion and Human Evolution (2017)—have long noted the association between gods and kings that surround questions of sovereignty. Graeber and Sahlins draw a helpful distinction between, on the one hand, divine kingship as “the ability to act as if one were a god . . . to rain favor, or destruction, with arbitrariness and impunity,” and, on the other hand, sacred kingship which is “to be set apart” for the sake of “confining, controlling, and limiting” unaccountable divine power (pp. 7-8). The complexity and scope of their arguments are beyond our immediate concern, but one can see how appeals to divine kingship—whether God is king or the king supposedly divinely appointed—institute a specific conception of arbitrary power in the heart of the political, and, unless confined by other powers (sacred or not), legitimate and unleash uncontrolled and dangerous forces. I leave it to the reader to consider whether or not this describes our current political culture where presidential powers collide with constraining congressional forces.

Yet, while John of Kronstadt's saying can be used to envision a political theology, that is, an account of political sovereignty grounded in godly power, it is not yet a political theology, since on its face it tells us nothing about the supposed character of God. Here is another conceptual piece of the puzzle. And on this point something seems amiss in the appeal to divine kingship. As Bellah has shown, the so-called “axial religions,” like the Abrahamic religions, entail a moral revolution in religion important for human social and political evolution. A conception of the kingship of God as arbitrary power acting with impunity no doubt has some resonances in some of the texts of Christians, Muslims, and Jews. (Analogies can be found in other religions.) But it is also the case that God is believed to be compassionate, merciful, and loving. (Analogies once again abound.) In other words, packed into the word “God” as used in these traditions are moral properties and capacities wherein the divine limits its own power in relation even to those who reject its sovereignty. This is partly why Tocqueville detected in Americans’ concern for freedom and equality a biblical background to “democracy in America.”

There is one last piece in the puzzle that will help us think about challenges facing this nation, and perhaps not this country alone. The problem is that language about "Christ the King," God as "all-powerful," "Christian soldiers," and the like, saturates the rituals, hymns, holy-days, and lectionaries of at least Christian churches, if not also other religious organizations. So, in the face of the “Trump Prophecy,” perhaps religious people of all stripes would do well to consider the place of unconstrained and arbitrary power in political life lest we devolve into endless strife. Alfred North Whitehead once noted, “The creation of the world—said Plato—is the victory of persuasion over force” (Adventure of Ideas, p. 83). The hope and struggle for that victory is the work of democracy precisely through debate and persuasion. It would seem, then, that democracy seeks to constrain the triumph of wanton force and is, therefore, anything but hell on earth. But the most crucial pieces of the puzzle are “we the people” committed, religiously or not, neither to heaven nor hell, but to the labor of self-government through persuasion.

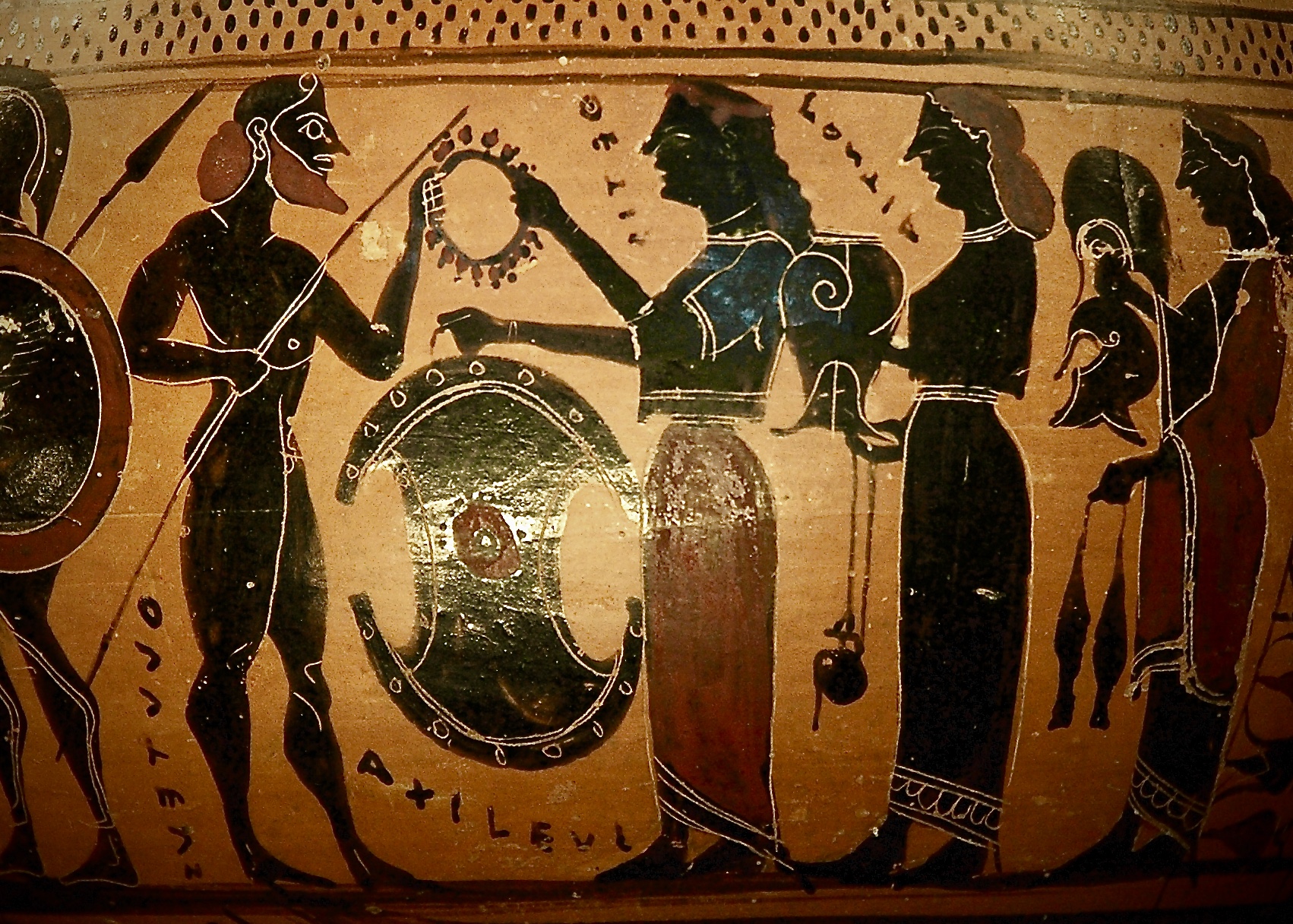

Image: Thetis gives her son, Achilles, his weapons—including his shield—newly forged by Hephaestus; displayed on an Attic black-figure hydria, ca. 575–550 BCE. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

William Schweiker (PhD’85) is the Edward L. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of Theological Ethics at the Divinity School. William Schweiker (PhD’85) is the Edward L. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor of Theological Ethics at the Divinity School. |

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD student in Religions in America at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.