The Expanded Spelling of "koinonia"

Though as an Indian I take a certain pride in the accomplishments of Indian American children, I generally do not follow closely the spelling bee contests where they emerge as winners in most years

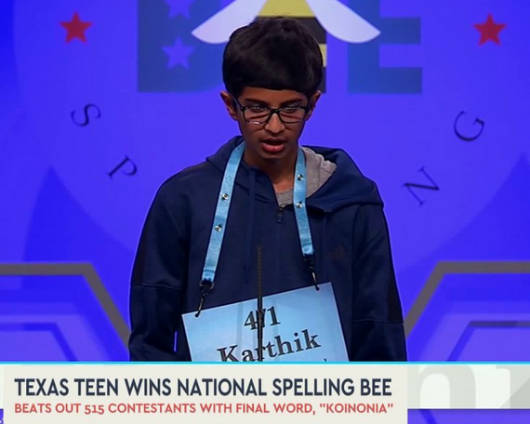

Though as an Indian I take a certain pride in the accomplishments of Indian American children, I generally do not follow closely the spelling bee contests where they emerge as winners in most years. Still, I could not help but take notice when fourteen-year-old Karthik Nemmani went on to win the 2018 Scripps National Spelling Bee on May 31 by spelling the word koinonia. As a student of Christian theology I am, of course, familiar with this word. When the Christian scriptures and liturgy were translated from the ancient tongues into languages spoken by the masses, koinonia lingered on in its original Greek. It is widely used in churches and easily understood by ordinary lay Christians. What struck me as particularly interesting was the meaning attributed to koinonia by those connected to the spelling bee contest and the media: “the Christian fellowship or body of believers.”

Though as an Indian I take a certain pride in the accomplishments of Indian American children, I generally do not follow closely the spelling bee contests where they emerge as winners in most years. Still, I could not help but take notice when fourteen-year-old Karthik Nemmani went on to win the 2018 Scripps National Spelling Bee on May 31 by spelling the word koinonia. As a student of Christian theology I am, of course, familiar with this word. When the Christian scriptures and liturgy were translated from the ancient tongues into languages spoken by the masses, koinonia lingered on in its original Greek. It is widely used in churches and easily understood by ordinary lay Christians. What struck me as particularly interesting was the meaning attributed to koinonia by those connected to the spelling bee contest and the media: “the Christian fellowship or body of believers.”

The current focus on koinonia took me back almost half a century to a debate between two Indian Christian theologians, Lesslie Newbigin and M. M. Thomas, on the meaning of that word and whether membership in the visible fellowship of the church is integral to all Christians including, especially, converts from other faiths. The debate assumed special significance in India, since conversion from Hinduism to Christianity often led to a radical break with one’s own social and cultural past and an identification with a new community. Two questions were key: Is it possible to become Christian and yet remain culturally a Hindu? And can Christ-centered fellowships within other religions be a substitute for the organized church?

Newbigin, an Englishman who served for many decades as a missionary and bishop in India, argued that one’s personal commitment to and belief in Jesus Christ needs to be nurtured within the fellowship of the church. As to whether or not it is possible to have an authentically Christian fellowship within a Hindu milieu, he argued that a person who is culturally and socially part of the Hindu community is, by definition, a Hindu. If that person’s allegiance to Christ were to be accepted as decisive—therefore overriding her/his obligations as a Hindu—then that allegiance must take a visible, that is, social, form. Such a person would need to have ways of expressing the fact that s/he shares this ultimate allegiance with others, and these expressions would necessarily have social, cultural, and religious elements. In other words, Newbigin seemingly rejected as sociologically and theologically unrealistic any form of Christian witness in which the church is not centrally involved.

Thomas was a lay person and Christian social thinker who took a broader view of Christianity that at times spilled over outside the framework of the organized church. He argued that one of the clearest signs of Christ’s work in the contemporary world was the renaissance of all religions. In India he pointed to the case of neo-Hinduism. The figure of Jesus Christ, as distinct from Christianity or western culture, was the symbol of many neo-Hindu movements in the nineteenth century, even as Christian missionaries insisted that Christ, Christianity, and the church constituted a single package. For Thomas, the acknowledgment of Christ within the Hindu renaissance opened up a set of questions surrounding Christ-centered fellowships in other faith or secular contexts. He believed that while the new humanity inaugurated in Christ affirmed the church, it also widened the horizons of the church. In terms of interreligious conversion, the issue was neither the participation of the convert in the visible Christian fellowship nor the outright denial of the church, but rather the transcendence of the church over any individual religious community, which makes possible the church’s taking form in all religious communities. What, then, should be the nature of the fellowship of those who acknowledge Christ as in some sense central to and decisive in their lives and yet, for social or cultural reasons, opt to remain outside the organized church? What form(s) could the church take in pluralistic contexts?

The debate between Newbigin and Thomas soon turned to the meaning of koinonia. Thomas argued in his work Salvation and Humanization: A Crucial Issue in the Theology of Mission for India (1971) that the word koinonia in the New Testament does not refer primarily to the church or to the quality of life within the church, but is instead the manifestation of the new reality of God’s domain at work in the world. Therefore the religious fellowship in the church and the human fellowship in secular society both partake in the reality of Christ and the history of salvation. This broader meaning of koinonia could be applied to the Indian context where interreligious conversion is a socially and culturally sensitive topic, as it involves changes not only in one’s religious faith but also in food habits and other aspects of social life. Newbigin, on the other hand, had affirmed in his book The Finality of Christ (1969) that turning to God necessitates membership in a specific kind of community. He argued that the New Testament admits nothing like a relationship with Christ that is purely mental and spiritual, disembodied from any of the structures of human relationships. At the heart of this debate, finally, was whether it is possible to form a religious fellowship that would remain culturally Hindu while religiously separating itself from Hinduism (rejection of idols, et cetera) and explicitly recognizing Jesus as “Lord and Savior.”

The Newbigin-Thomas debate was not resolved, and its implications can be felt in the present. Until a few decades ago countries like India were set apart by virtue of their pluralistic and multireligious character. Now that label can be attached to a variety of other societies. Robert P. Jones, in his 2016 book The End of White Christian America, argues that for most of the history of the United States, White Christian America—“a cultural and political edifice built primarily by white Protestant Christians”—functioned as a closely knit community, setting the tone for national policy and shaping America ideals. However, this has changed in recent decades, with the U.S. predicted to be majority nonwhite for the first time by 2042.

The demise of America’s white Christian majority holds both promise and peril for those concerned about religious harmony, racial justice, and establishing an egalitarian social order. In addition to Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Jews, and atheists living side by side, our current socio-political climate has produced unanticipated “mixed fellowships,” and new questions. What is the meaning of koinonia when Christian churches provide sanctuary for fleeing Muslim families? Or when the Hindus in Houston work with the local Cambodian Buddhist community, whose members’ lives were torn apart by Hurricane Harvey? Or when women and men worship side by side at the Qal’bu Maryam mosque in Berkeley, California, thereby redefining gender roles and opening new vistas for religious fellowship? Cutting across theological divides and geographical contexts, we are reminded time and again that religious fellowship is so often intertwined with human fellowship, in the process expanding the definition of koinonia in our times.

Photo Credit: ESPN (screenshot)

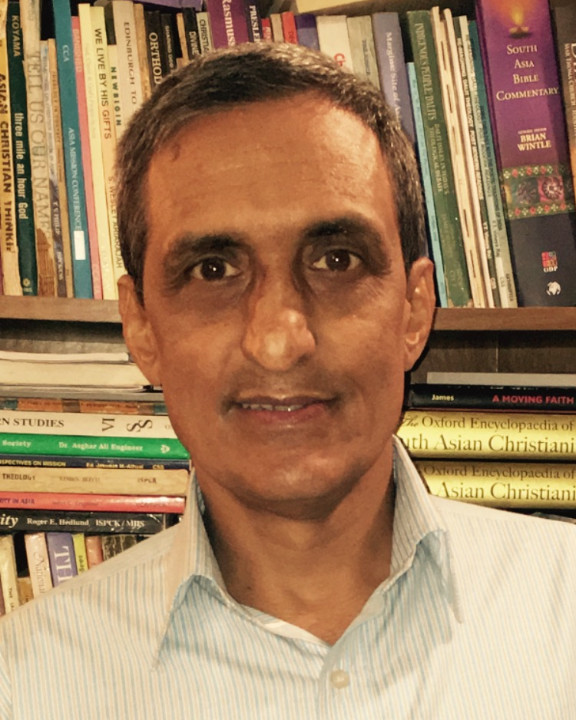

Jesudas M. Athyal is acquiring editor at Fortress Press in the areas of South Asian theology and ecumenical theology. He is a past president of the New England-Maritimes Region, American Academy of Religion (NEMAAR). He served earlier as associate professor of Dalit theology and social analysis at the Gurukul Lutheran Theological College, Chennai, India. He has authored and edited a number of books and was editor of Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures (ABC-CLIO, 2015) and associate editor of the two-volume Oxford Encyclopedia of South Asian Christianity (Oxford, 2012). Jesudas M. Athyal is acquiring editor at Fortress Press in the areas of South Asian theology and ecumenical theology. He is a past president of the New England-Maritimes Region, American Academy of Religion (NEMAAR). He served earlier as associate professor of Dalit theology and social analysis at the Gurukul Lutheran Theological College, Chennai, India. He has authored and edited a number of books and was editor of Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures (ABC-CLIO, 2015) and associate editor of the two-volume Oxford Encyclopedia of South Asian Christianity (Oxford, 2012). |

Sightings is edited by Brett Colasacco (PhD’18). Sign up here to get Sightings by email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.