The Blinding Idol

Daniel Owings discusses the shortcomings of idolatry imagery for understanding Donald Trump

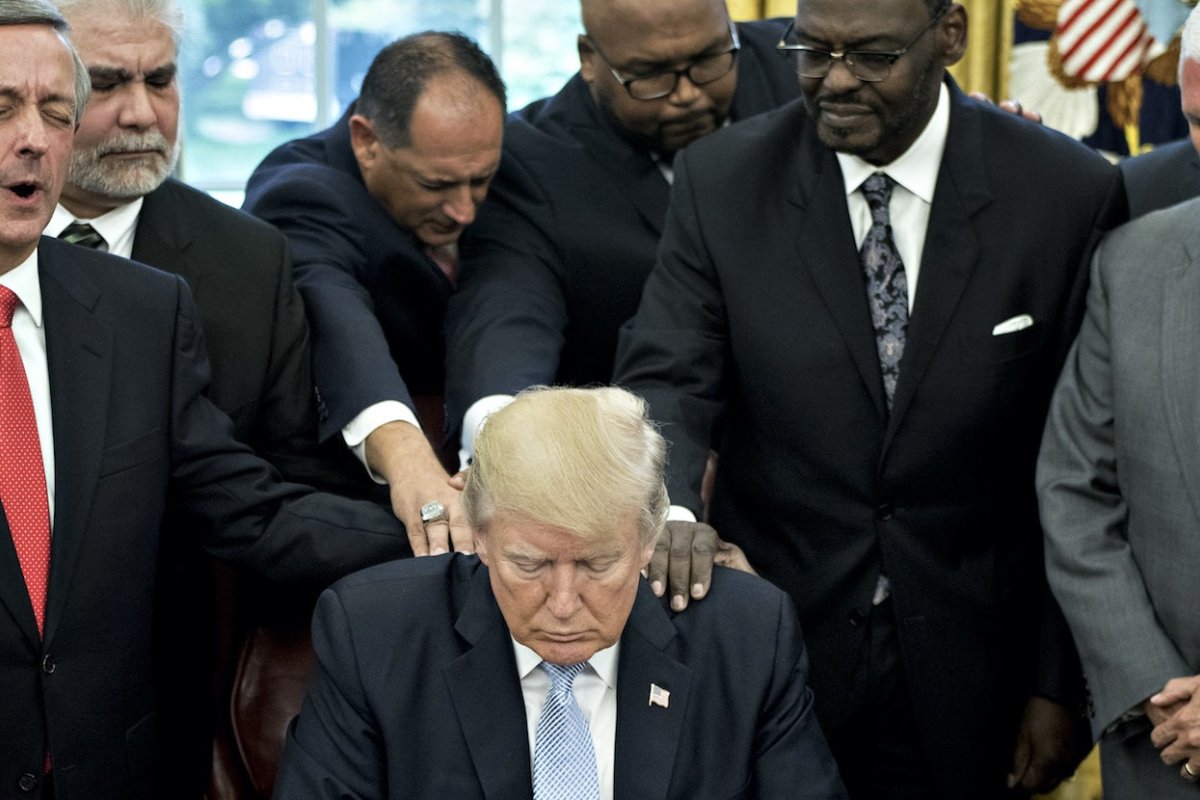

After Donald Trump won a presidential election with strong support from white evangelical Christians, it has become somewhat commonplace to depict him as an idol. The image is, indeed, too good a fit to pass up: a glittering golden statue, gaudily displaying empty promises of material opulence and worldly power, who so thoroughly seduces his devotees to abandon their professed religious values that they mistake their devotion for true piety. The early-twentieth-century theological critiques of fervent nationalism as idolatrous by such giants as Karl Barth and Reinhold Niebuhr once again suggest themselves as all-too-relevant, to be sure.

I would agree with the basic contours of this characterization of Trump’s relation to white evangelicals, but I would also caution that it allows for too easy a story on the part of those who tell it. Idolatry has always been a troublesome sort of word; at a minimum, one could make the case that discourses around idolatry developed around the nationalistic impulses of ancient Israel, seeking a marker to make a clear delineation between those who were chosen of God and everyone else, thereby justifying horrendous atrocities against neighboring peoples. More importantly, to label something as idolatry tells us much more about the one using the label than it does about the moral valence of the putative idol. As Moshe Halbertal and Avishai Margalit have suggested, what someone counts as an idol depends entirely on what they claim to be the nature, desires, and revelations of The True God, and the chief business of scholars of religion is to raise questions about any such claim (236ff.).

In this instance, I think the most important recurring aspect of “idolatry” as it is has shown up in the Abrahamic traditions is its association with blindness. Isaiah 44:9-20 links the wooden or stone idol’s powerlessness to see with the idolater’s own “deluded mind” (v.20) that sees no incongruity in using half of a log to boil his supper and the other half to make a god for himself. In the letter to the Romans (1:18-25), Paul claims that idolatry is both crime and punishment; because the idolaters have ignored the clear evidence of God’s hand in creation and failed to render their creator his due honor, “their senseless minds were darkened” (v.21). Likewise, the Qur’an (6:22-26) depicts idolaters as so self-deceived that they are astonished to even hear they have committed idolatry; God has “cast veils over their hearts and made them hard of hearing lest they understand” (v.25). In all of these cases, the idolaters’ stubborn and tragic failure is to perceive the true God, and thus their blindness to the enormity and absurdity of their own sin against him, and it is a central defining feature of what makes them idolaters. The movement of the eyes to the idol as equivalent to the occlusion of a truth is as obvious as it is inconvenient.

While we might of course note the convenience of such an epistemological schema for making religious difference a punishable offense rather than a simple matter of divergent upbringing, we may nevertheless use it to help clarify our thinking on this matter. If we are to understand Trump as an idol, we must ask whom he renders blind, and to what. For those who support him, the idol that is Trump obscures the putrid carcass of American racial injustice and its coalition with income inequality that has been stinking up the doorstep while efficiently fertilizing the ideology that has upheld such blights for the past few centuries. But for those of us who didn’t vote for him, we might say he represents a negative idol—a graven image in bas-relief, if you will. Every time he makes a mockery of Presidential decency and decorum, whether it be with a tweet that undermines our international standing or callously abandoning our military allies, he tempts us with the thought that the only thing that really matters is getting rid of him. We tell ourselves we can solve all our problems by impeaching him, or at least ousting him at the ballot box in 2020. With a president who knows how to behave themselves, we too cherish the thought of Making America Great Again. With each new soundbite about impeachment—I speak from personal experience—we all too easily allow ourselves to forget the systemic and very deliberate inequalities and oppressions at the foundations of those institutions that we wish to return to normalcy.

Make no mistake, I think that the world will be a better place once Trump is no longer in the White House. But we must not blind ourselves into believing our work is done when that happens.

Sightings is edited by Joel Brown, a PhD Candidate in Religions in the Americas at the Divinity School, with assistance from Nathan Hardy, a PhD Candidate in the History of Christianity at the Divinity School. Sign up here to receive Sightings via email. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.