The Bible as/and Literature

W

W. W. Norton & Company’s recent publication of Robert Alter’s The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary is at once a cultural accomplishment of a very high order, and an opportunity to think about the places and the spaces that “the Bible” occupies in contemporary discourse.

W. W. Norton & Company’s recent publication of Robert Alter’s The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary is at once a cultural accomplishment of a very high order, and an opportunity to think about the places and the spaces that “the Bible” occupies in contemporary discourse.

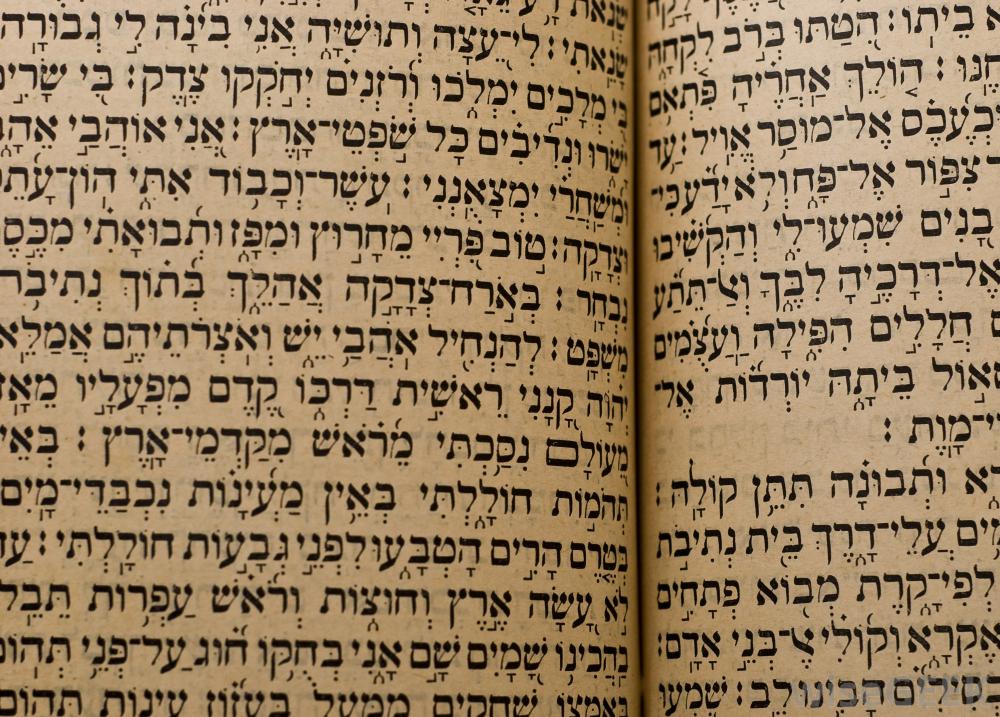

First, a caveat: “the Bible,” as we shall see (and as many readers understand), signifies different things in different contexts. Most often, and in its strictest sense, it is the Christian designation for the set of books that comprise the Old and New Testaments. It is sometimes the Jewish designation for “Word of God” encompassed by the Pentateuch, the Prophets, and Writings. It is also deployed in some cases by religions other than Judaism or Christianity whose own scriptures actually incorporate, reproduce, or revise portions of “the Bible” (e.g., Islam, Mormonism). Other uses are colloquial and as such less concerned with the components of composition and more with assertions of authority (“I swear on the Bible,” or “I did it by the Bible”). Robert Alter understands all of this perfectly well, and he is so good at what he does that the implications of his particular position can seem understated in the context of what he accomplishes.

A literary critic whose span never seems to exceed his grasp, Alter’s newest publication is a summa of the work he has steadfastly undertaken since the 1980s when, as an already accomplished scholar of comparative literature, he began to write books such asThe Art of Biblical Narrative and The Art of Biblical Poetry. In these books, “biblical” references the texts composed in ancient Hebrew that are the basis of the Jewish religion.

Alter’s work is at once restorative and polemical. Restorative, in that he seeks nothing less in his translations than to produce a work that approximates as far as possible in its aesthetic value the cultural currency and influence of the King James Version (KJV). Polemical, in that the restoration is required by the unhappy fact that the Bible’s beauty, and resultant cultural resonance, has been compromised by the unsalutary influence of historical-critical methodologies of interpretation that see the Bible’s chief value as historical, even quasi-archaeological (i.e., as comprised of sources which index the thought and practice of various competing religious communities in the ancient Near East). By enshrining this value above all others, scholars who do historical-critical study foster decidedly un-musical ears that fail to appreciate the cadences and dignity of the Hebrew. Little gained, a lot lost.

There is compelling, if intuitive, merit in Alter’s position. The KJV is indisputably a powerful, if no longer regnant, force in Anglophone culture worldwide. Whether this position exhausts the cultural functions of the Bible, or even fully encompasses them, is at least debatable. Some of that debate would have to focus on Alter’s bogeyperson, the practitioner of historical criticism; questions of textual composition and authorship are as old as the religions that attend to the biblical texts. Further and in some ways more forceful debate would ensue with a full consideration of the history of the Bible’s reception (which encompasses the history of intra-religious debate and commentary, as well as rhetoric and theology). None of this work is uninterested in the aesthetics of the Bible; but it is cognizant that the Bible’s literary quality raises foundational questions about a religion and its self-understanding. All of these practices predate not only the publication of the KJV (1611) but also the particular moments in biblical scholarship of the mid- to late-nineteenth century that are focalized in the methodology that Alter bemoans, e.g., Julius Wellhausen’s documentary hypothesis and Albert Schweitzer’s quest for the historical Jesus.

Consider first the complementary, if in the end very different, work of Alter’s fellow literary critic, Northrop Frye. Frye’s Bible is the King James Bible. In The Great Code and Words with Power, Frye presents formal readings of the KJV (including the New Testament). His motivation? Not to provide a literary guide to the Bible’s style, but to promote biblical literacy: absent mastery of the KJV, Frye realized, he could not hope to understand William Blake. For Frye, this meant reading the King James Bible in some approximation of the way he surmised that Blake did: “from cover to cover,” repeatedly, until a sense of its internal form and structure became clear. Alter’s attention to style has a counterpart in Frye’s attention to form: Frye’s Bible is not so much a set of narratives and poems as a book of books that tells the story of human history from the creation of the world to its end. For Alter, it is the Bible as literature; for Frye, it is (per his subtitle in The Great Code), the Bible and literature. One is a claim of aesthetic merit, the other of cultural context.

Style and form do not cancel one another out, and many Jews and Christians regard their Bibles as providing both. What is interesting about the abiding fascination of two indisputably great literary critics with the KJV is that they live in an age in which the authority that undergirds that specific object of cultural fascination is in fact unavailable. Whatever one thinks of historical-critical scholarship, it serves no King; and the authority the KJV enjoys, while undeniably aesthetic and formal, was, is, and in some sense always will be, political. The translators whom Alter so courageously and brilliantly emulates understood this well; they wrote not to overturn wrongheaded historicism but to quell the seemingly ubiquitous cavils of religious dissent. For them, the Bible was not solely or even primarily a literary work; it was the key to salvation, and to make it available to everyone required the endorsement of their King. For the KJV translators, aesthetics mattered: but the connection with salvation was urgent, and its urgency was, in the deepest sense, a merging of the religious and the political.

The Bible’s cultural force is not sufficiently encapsulated by its understanding “as,” or for that matter, “and” literature. In the end, “the Good Book” defies even the most august and admirable of cultural reductions.