Announcements

I need to start with an apology

I need to start with an apology. Today’s column departs from this publication’s modus operandi—“sighting” religion in current events in global cultures. Instead, with your forgiveness and permission, I’d like to use my space this month to reflect on one of the major questions that animates life in Swift Hall—not just lately, but for decades: What does it mean to be an institution devoted to the “academic study of religion”?

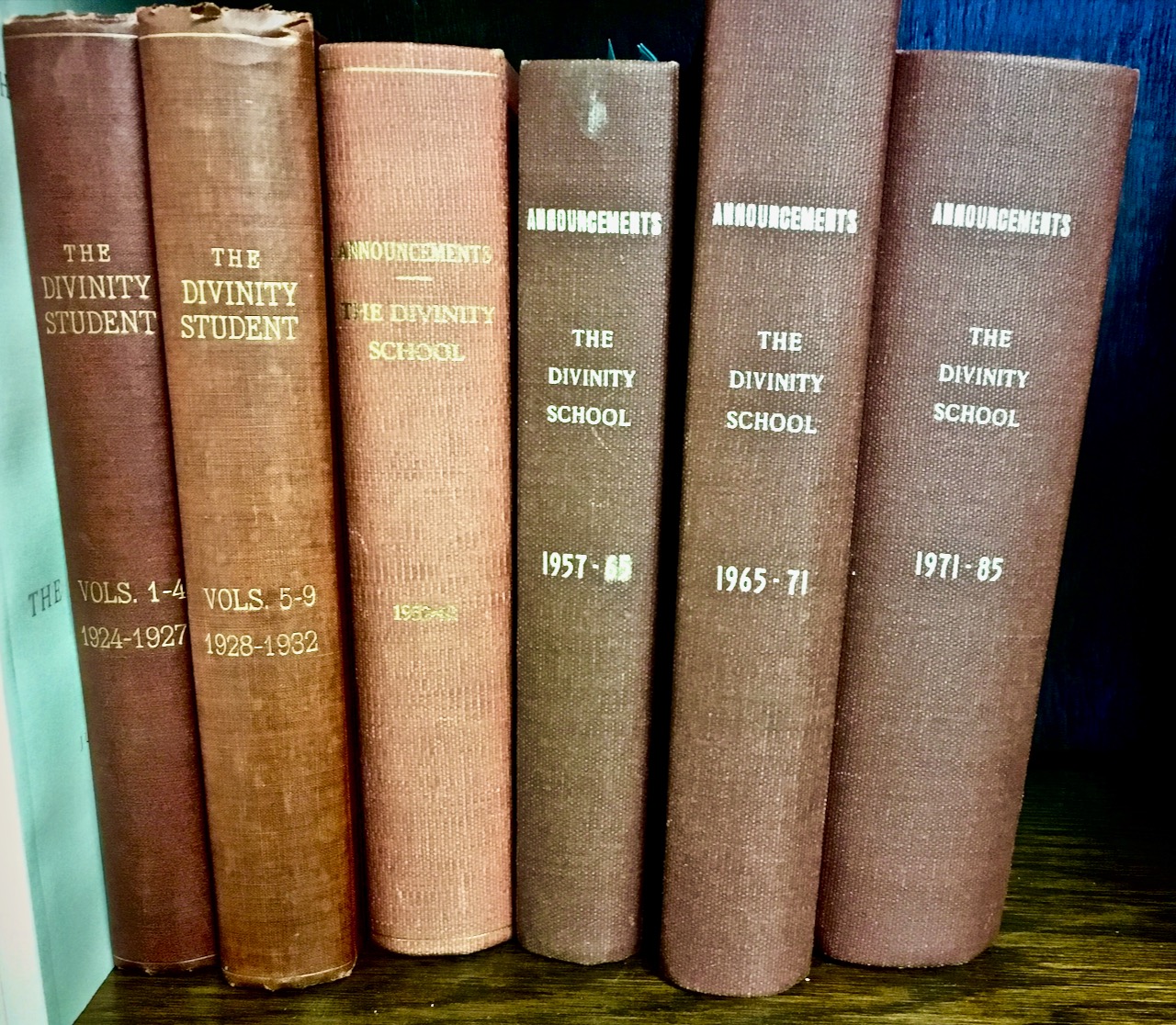

I need to start with an apology. Today’s column departs from this publication’s modus operandi—“sighting” religion in current events in global cultures. Instead, with your forgiveness and permission, I’d like to use my space this month to reflect on one of the major questions that animates life in Swift Hall—not just lately, but for decades: What does it mean to be an institution devoted to the “academic study of religion”? When I arrived in the Dean of Students office a year and a half ago, I found on my bookshelf several volumes of the collected editions of the Divinity School “Announcements,” the publication offering technical information about the school’s degree programs and policies, faculty, courses, student life, fees and the like. The earliest version on my shelf is from 1934, and the bound volumes include the Announcements covering the next five decades, bequeathed, it would seem, from one Dean of Students to the next for more than a half-century.

The most obvious value of these tomes is administrative: if a doctoral candidate from 1965 shows up who wants to turn in his dissertation and graduate, I have the policy of the day to consult. But of course they provide even richer interpretive value as historical artifacts. As one with a scholarly interest in the history of the relationship between religion and American higher education, I am particularly drawn to what this collection might tell us about how one of the nation’s leading institutions for the academic study of religion conceived of and organized itself within an institution routinely held up as one of the finest American examples of a research university.

All of the Announcements, right down to the present day, make some appeal to the history of the Baptist Theological Union and the integration of the Morgan Park Seminary into the University at the time of its founding in 1890. (The earlier versions of the Announcements explicitly link the Seminary’s move to the university to John D. Rockefeller’s philanthropic gifts to the University.) Through that appeal, the Divinity School aims to ground its claim to centrality in the life of the University, as though reminding readers—who, remember, are primarily if not exclusively students and faculty of the Divinity School itself, rather than those in, say, the Law School or the Division of Biological Sciences—that we were here first, that we were the jewel in the eye of William Rainey Harper, the founding president of the University (and a Hebrew Bible scholar).

The 1934-35 Announcements offer the following self-narration: “The purpose of the Divinity School is primarily and chiefly to fit men and women to serve the Christian church in: (1) the pastorate; (2) the mission field; (3) Christian teaching; (4) other religious vocations. In addition to such professional preparation the Divinity School offers a large number of courses intended for those who wish to make the study of religion a part of their general education.” The inclusion of women in this statement is genuinely notable, and reflective of the University’s co-ed philosophy from its founding. But, 85 years later, the identification of the school’s primary purpose as training people who will serve the Christian church through their careers seems remarkably foreign. Not only are no other religions mentioned here, but the word research is absent as well.

By the late 1960s, however, we begin to see some significant changes, reflective of broader changes in society and in academe. Consider, for instance, that in 1964 the National Association of Biblical Instructors renamed itself the American Academy of Religion. With this in mind, consider the 1967 Announcements, which narrate the school’s purpose thus: “To engage in disciplined theological research and inquiry into the nature and task of the Christian faith at the level of scholarship expected from an integral part of a great university” [emphasis added]. It continues, “The Divinity School has always stood for theological education of University quality in responsible relationships to the church and to culture.” Of all the statements, this one, to my mind, is the most striking, as the tensions it bears are so heavy and so poorly concealed. On the surface, its appeal is clear—to be taken seriously by the “great university” of which the School is a part. The value of studying “the Christian faith” is manifestly not self-evident, and the justification for the school is that the quality of its scholarship is on a par with any other school or division.

By 1971, a transformation—of sorts—had occurred. After a nod to the University’s spirit of “creative independence,” the statement grounds its claim historically—now reaching back past Harper to the days of the Civil War’s end: “As the predecessor of the University and its oldest professional school, the Divinity School promotes systematic research and inquiry into the manifold dimensions of religion. While the School is mindful of its Christian origins in the Morgan Park Seminary of the Baptist Theological Union, chartered in 1865, it has consistently drawn its faculty and student body from the various Christian traditions as well as from the major religions of the world.” Significantly, the statement still makes mention of Christianity, even as it acknowledges other religions.

The statement in the Announcements today positions “religion” in the center, and clearly denotes academe as the main professional trajectory for Divinity School students, with “ministry” (a term that still emits Christian overtones) as an alternative: “From its inception, the Divinity School has pursued Harper’s vision of an institution devoted to systematic research and inquiry into the manifold dimensions of religion, seeking to serve both those preparing for careers in teaching and research and those preparing for careers in ministry.”

Where to from here? The challenges today of course bear both continuities and discontinuities with previous historical moments: the tensions of Wissenschaft versus Bildung (loosely, scientific study and characterological formation); a sense of responsibility only to truth versus a need to justify intellectual work to the state or economy; a commitment to the production of new knowledge with a simultaneous mastery of the knowledge of the past—all tensions inherent in the university enterprise. They have been present as long as the modern research university has existed, and there is little reason to think (or desire) that they will cease.

Yet, today, the meaning of religion, much less its study, is far from agreed upon, and the value of the enterprise does not appear to be self-evident to someone like Jeff Bezos in the way it was to John D. Rockefeller. Nor is it so clear what a life of scholarship means, nor what a career in “ministry” is. While many of the Divinity School’s graduates go on to careers with familiar dimensions (for instance, as university faculty or church pastors), many are also crafting new vocational forms with their Divinity School educations, and virtually everyone is struggling to keep up with the pace of change.

Historically, as now, the Divinity School’s responses to cultural shifts both reflect and help to author the story of religion, religious people and communities, the university, and society. What does the academic study of religion mean? How does it contribute to human flourishing—and does it need to justify itself that way? How do the School’s faculty and students translate their work into knowledge that can be understood by broader publics? How does the School organize knowledge production, and how does it educate graduates who will be able to work comfortably both within and at a critical remove from religious traditions? What is the proper calibration of depth of training within fields and subfields, on the one hand, and breadth of knowledge on the other? These are the kinds of questions and tensions that have been at the intersection of religion and higher education for a good long time now, and continually wrestling with them will, I hope, make us all better “sighters” of this thing we call religion.

Joshua Feigelson is Dean of Students at the Divinity School.

Joshua Feigelson is Dean of Students at the Divinity School.